Grape Island

I am catching up on the older trip reports. This one took place in August 2018.

That August turned out great, with the sun and the heat teasing the hundred-degree mark.

And so, one of those lazy August days we (Ben, Jeremy and I) took off under sail.

The day before Lena had sent us an article in the Boston Globe about whales sighted in Boston Harbor, with one of them spectacularly breaching by Deer Island.

As we took off the mooring under the sails and unhurriedly proceeded towards the outer harbor, we were mentally getting ready to meet the whales.

Instead, we met an LNG (liquefied natural gas) tanker. As usual, the tanker’s arrival had precipitated a big show in the harbor: a state police helicopter was patrolling overhead, and a police speedboat approached us very quickly.

The police officer was very friendly and greeted us thusly: “Hello! How are you doing? It’s a beautiful day, isn’t it? A tanker is coming this way, so please get out of the channel, and head that way, towards those rocks.”

I was quick to acknowledge the order; it is better not to argue with the police. Ben, who was at the helm at that moment, had never been in a situation like this before and was confused by the officer’s demands. I explained that we should prefer underwater rocks to armed people.

Still, we didn’t hit those rocks beyond Castle Island — rather, just stayed somewhat outside of the channel. From there we watched the procession of the tanker surrounded by tugboats, Coast Guard cutters, and speedboats of all the different kinds of police. The police chopper, meanwhile, was circling really low, leaving a trail of foamy water behind. To this day I have no idea what point it was trying to make.

By then it was time to decide on the trip destination. The heat required a swim stop. Jeremy had never landed on an island, so it made sense to bring him to an island — and stop there for swimming all the same. The wind was not great anyway, so there was no harm in stopping. Ben looked at us with slight sadness and shrugged: OK, let’s do an island if you guys can’t live without it.

As we were discussing islands, somebody mentioned Bumpkin Island. That island was recommended to me multiple times by our mutual friend Alex. Alex had been to Bumpkin once, and apparently got enchanted by it.

Meanwhile I myself had never been to Bumpkin: it is located on the opposite side of Boston Harbor, and away from our usual ways. The wind was light, which frankly put the entire enterprise in question — but at least it was coming from the advantageous, southwestern direction, so it was worth a try.

Having agreed on the general plan, we took off along the southern route: past Spectacle Island, under an invisible bridge to Long Island, past Hangman Island and Peddocks Island, towards the town of Hingham, a southern Boston suburb.

The wind kept turning on now and then, only to turn off and fill our hearts with pessimism. Still, the boat was proceeding in the right general direction, just slowly. That’s why at some moment we decided not to be greedy and instead of Bumpkin head towards Grape Island. It is located in the mouth of the Weymouth River, a couple of miles closer than Bumpkin Island.

No sooner said than done, by noon we had already reached the western end of Grape Island, looked around, and anchored between the island and the green mark “13”. Anchored under sails, I must note, not using the engine — just as real sailors do. Jeremy and I immediately jumped into the water. The water in Boston Harbor is really warm not hat often. One should never miss an opportunity!

While swimming, I noticed a pronounced tidal current: it took time and effort to get to the boat’s bow, while you got immediately pushed back to the stern. Need to pay attention, I thought, otherwise you can end up pushed into the open ocean!

After that, it was time for the island raid. We inflated our dinghy, got the oars, rowed towards the shore, squeezed between big rocks in the water, and landed on a narrow beach covered by rocks and shells.

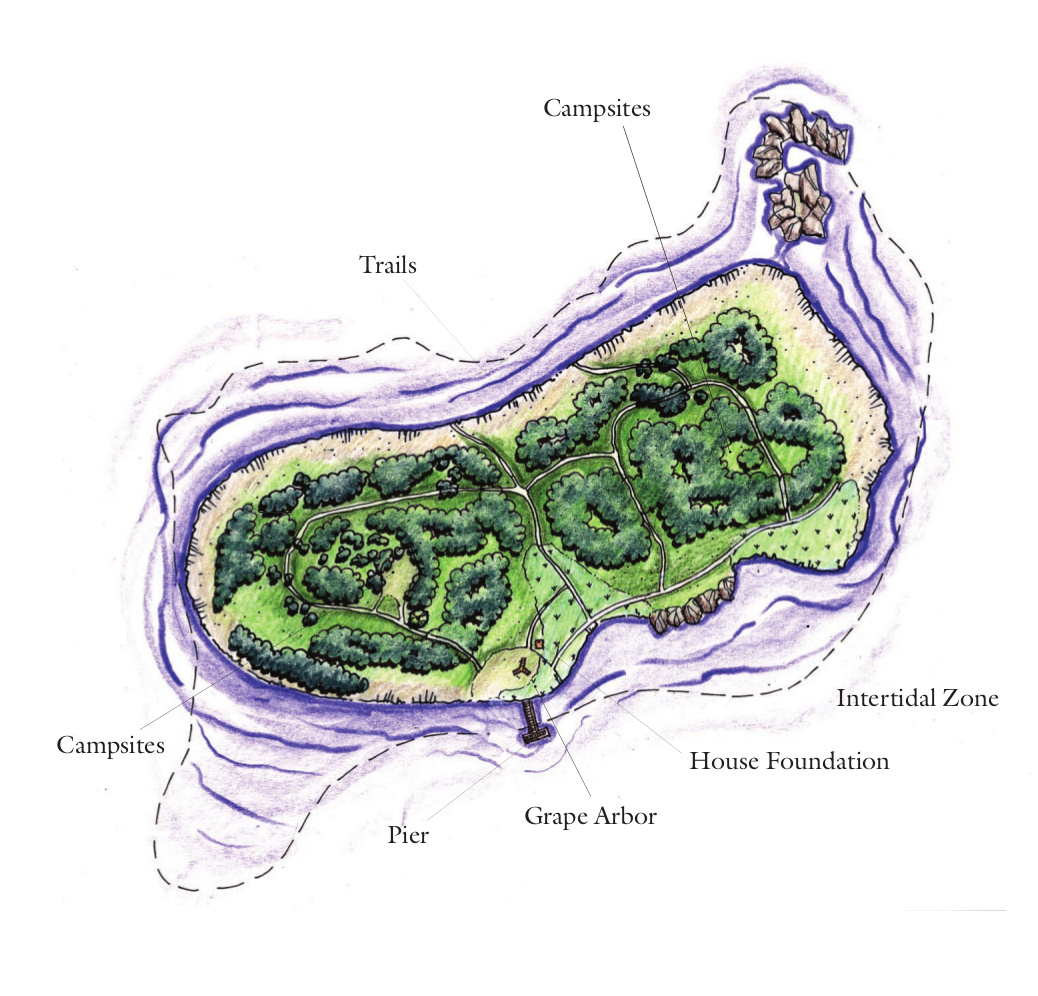

Grape Island consists of two very different worlds: the narrow coastal strip around the island and the inner, wooded part.

We found an entrance into the woods — a trail marked by a broken-off part of a blue kayak — and stepped into a different world.

Out of all islands explored so far, Grape Island looked to me the least touched by human presence, even though the closest point of the mainland is just a third of a mile away. (The closest mainland towns are Weymouth and Hingham; it only feels distant if you are coming from Boston.)

In the woods, besides trees, there were thickets of sumac, dandelions, and such. And suddenly there was a spot of red leaves, and the heart turned uneasy: the fall was just around the corner.

Unlike many other Boston Harbor islands, there were no military fortifications on Grape, and no interesting ruins remain. There exists one interesting story, though.

It turns out that the second, pretty obscure confrontation between the British soldiers and the local insurgents during the American Revolution took place on Grape Island. Or almost took place, as you will see.

As you remember, the trouble started in April 1775, when a British army regiment advanced to the town of Concord to disarm the local militia. To their surprise, the armed people refused to disarm, had utilized their weapons accordingly, and pushed the British back to Boston, laying siege on the city. That was the first armed confrontation.

In May 1775 the blockaded British used their Navy ships to... get some hay for their starving horses. Back then Grape Island belonged to the resident of the nearby town of Hingham, the prominent Tory by name Elisha Leavitt. It was he who invited representatives of the lawful authorities to his island, to get whatever suits their fancy.

When they saw the coming Navy fleet, the residents of Weymouth and Hingham had sounded the alarm: they thought that the British were preparing an invasion or trying to break the siege. Bells were sounded in the churches, and all able-bodied minutemen had gathered with their weapons.

When they gathered on the beach, they first realized with relief that the invasion rumors were greatly exaggerated: the British were just loading their boats with the hay of Elisha the collaborator. Unfortunately, it was all happening around low tide; the water was too shallow for the resistance fighters to get to their boats and engage the enemy. Grape Island was close enough to see what was going on, but too far for aimed fire. The militiamen kept firing anyway, but couldn’t harm the British, who shot back with the same exact outcome.

For a few hours the militiamen looked helplessly as the British entered the barn, took the next sheaf of hay, brought it to the pier, loaded onto a boat, and went back for the next sheaf. Finally the tide brought enough water to raid Grape Island. Seeing that, the British undocked and sailed back to Boston, while both sides kept harmlessly firing at each other. When the insurgents got to the island, all the British were already out of reach, so they just burned the remaining hay (80 tonnes!) and the barn too for good measure.

However, that didn’t feel like good enough revenge, and so the local residents showed up with torches and pitchforks at Elisha’s house in Hingham. Things could turn very wrong, but the cordial Elisha showed up by the gate and offered his guests cheese and crackers — and a barrel of rum. After an improvised party, they all parted as friends. Oh, the old-fashioned simplicity!

It was this epic fight, called “the Battle of Grape Island”, that forever entered the island into world military history.

For the sake of comparison, consider the Bunker Hill battle, the next battle between the insurgents and the British army. Both sides had lost around fifteen hundred people then. And all because nobody had the presence of mind to put forward a barrel of rum!

Eventually we walked across the island and ended up on the other side, by the ferry dock. Normal people start exploring the island from here. (We couldn’t do that because only ferries are allowed to dock at the ferry dock.)

Passing by weird dry tree trunks, we stumbled upon the only remaining trace of the historic human presence on the island: a crumbled house foundation.

This is how it looked earlier:

In this house, by the way, there lived all kinds of interesting people. Edward Rowe Snow tells anecdotes about a few of them.

One of them, for example, moved to the island soon after the Civil War. He called himself Captain Smith, though his real name was Amos Pendleton. In the past he was a slave-trading ship captain, a pirate and smuggler. Having retired from these profitable occupations, he decided to lay low on the island. It is not surprising then that he really treasured his solitude. When he imagined that somebody was coming over, he grabbed his shotgun which he kept by the door, and fired. Pretty quickly people learned to stay away from him.

In the beginning of the twentieth century the island’s caretaker was one Captain Billy McLeod who lived in that house for thirty four years with his wife. McLeod was still around when Snow started his explorations; Snow frequently visited McLeod at his house.

One day, McLeod was going for a walk on a beach and found a tiny seal puppy who lost his parents. McLeod brought him home and raised him. The seal stayed in the house — in a box behind the wood stove. Each morning he got out of the box, went to shore, swam in the sea, and then came back and knocked three times with his flipper. That was an agreed-upon signal: McLeod would not have opened the door otherwise.

Those were some people (and animals) who lived in the house which ruins we saw. The last residents left the island in 1940.

After the ruins we came to the dock. Next to the dock there was a meadow, and in the middle of the meadow there was a little vineyard: a trellis with grape vines. And the grapes were ripe! It’s unlikely that it survived since historic times; I think that it rather was the Park Service that had planted it. In this case, it was a great idea. Thank you!

Here is a view from the dock.

And a close-up on the grapes.

Having filled ourselves with the grapes, we headed back to the inner part of the island.

Grape Island is one of the few islands where camping is allowed. The campsites looked very simple: just numbered clearings in the woods for pitching a tent and a couple of composting toilets — these were all the services, so they didn’t break the wild vibe of the place much.

Not long before this Grape Island visit, my dad and I explored Lovells Island where we gorged on wild blackberries in some enormous quantities. I was waiting for something similar on Grape, but we didn’t see any edible fruits (other than the eponymous grapes) — or, at least, we didn’t recognize them as such. However, I’ve read later that there are numerous kinds of berries growing on the island, and park rangers even give tours of the most fruitful berry spots. This will clearly require further investigation.

As I said, the island consists of two different worlds. The woods are so thick that when you follow a trail, nothing reminds you that you are on an island in an ocean. Views open up very rarely — but when they do, they are well worth seeing. Here we suddenly saw Pushover, our boat riding at the anchor with distant Boston at the background.

After exploring most of the inner island, we ended up at the shore again, and followed it back to the dinghy. Life is very different here: shells, water, views, seagulls, boat, grass uncovered at low tide.

Here are a couple of Ben’s photos from there. On one of them there is yours truly with Slate Island in the background. It’s very close; we’d need to get there next time. On the other one there are houses of the town of Hull at the distance.

Following the shore, we got back to our dinghy. Before we start getting back to the Pushover, here is a so-called map of island by the Park Service.

By the time we loaded ourselves into the dinghy and started rowing back, the wind had built up significantly. Jeremy and I were making barely any progress against the wind, the waves and the current. Ben was looking at us skeptically, but we managed!

Back on the boat, we caught the wind in our sails, passed the narrow Hull Gut (a cut between the mainland and Paddocks Island) with the following current, and headed back home. And at home, we moored under sail again, not using the engine. What a remarkable day it was: a hot, summer day. The right kind of day.

We never saw the whale, though.

Subscribe via RSS