Great Brewster Island

The Approach

Great Brewster Island was the second accessible-only-by-private boat island that we’ve explored (after Rainsford Island).

As usual, we begin with an overview aerial shot found somewhere on the Internet.

Great Brewster Island sits in some eight nautical miles away from Boston, and belongs to the group of islands called the Boston Harbor outer islands. They take upon themselves the fury of the elements from the Atlantic. They shield the harbor with their bodies, so that the city could sleep well. Or, at least, better than if it were wide open to the ocean.

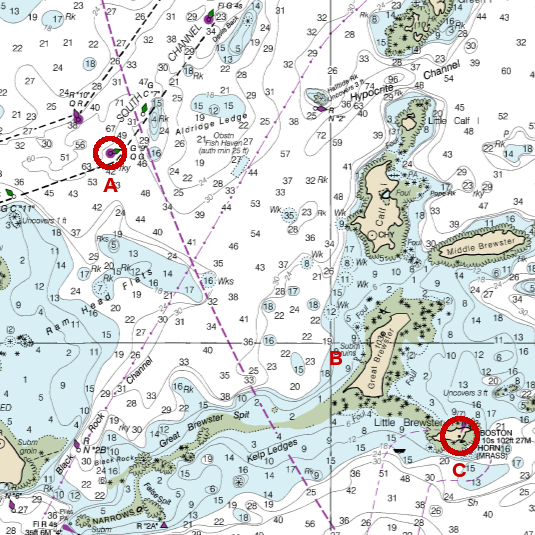

It is not easy to approach those hard-to-access islands, especially on a boat with a deep keel and a broken depth sounder. That’s why when my crew, Ryan, Sasha, Chris, and I, set out to explore Great Brewster Island on a nice September day two years ago, we follow the so called South Channel to the green buoy No. 9 (marked as G "9" Q G on the chart), and then our navigator (that would be I) pauses to think how to proceed.

Just look at chart:

Underwater rocks on both sides! Well, it couldn’t really be helped. I draw the line on the chart, figure out the required heading and tell the helmsman (the helmswoman, to be precise) where to steer.

On the photo: we leave the channel and can now see “our” island, Great Brewster, well for the first time (little bit to the left in the photo; in reality it was, of course, straight ahead).

Very soon we realize that the navigation here is easier than expected. The thing sticking up behind the island is the historic Boston Light, and it is enough to just steer towards it, looking back from time to time to maker sure that green buy No. 9 was still behind the stern. (It it weren’t, it would mean that we were being set sideways by current, and we would need to steer somewhat into current to compensate.)

The view back. The green buoy (on the photo to left of the fishing boat’s bow) is exactly dead behind our stern, just as expected (which meant that we were not being set by current).

Brewster

Great Brewster was named after a reasonably famous man—William Brewster (about 1566–1644), the elder and spiritual leader of the pilgrims that arrived in 1620 on the Mayflower. Brewster (who, by the way, was fleeing from King’s special service agents trying to arrest him for publishing pamphlets critical towards the King and his bishops) was the only university-educated person among the pilgrims. He served as the colony’s religious leader (until a real pastor has arrived from England), and also as an adviser to the governor.

Wikipedia tells us that no contemporary portraits of William Brewster survived. This stern bearded old man in a yarmulke is a reconstruction from a 1911 book. But to me it looks exactly in the pilgrims’ spirit. Let’s just agree that this is precisely how our good old Brewster looked.

In any case, we know that Brewster used to own some land on some Boston Harbor islands. Presumably, the name stuck since then. These days, four islands carry his name: Great Brewster, Middle Brewster, Little Brewster, and Outer Brewster. We have visited and explored Outer Brewster last year (a report is forthcoming), and the other two are definitely on my exploration list. (Little Brewster is the home of Boston Light.)

Overall, it’s hard to find particularly epic events in the Great Brewster history. In 1917 the federal government purchased the island to do some military construction, but then the World War I unexpectedly came to an end, and the government lost its interest to pursue those plans. In the nineteen-twenties and thirties there were a few “summer houses” on the island; the federal government made its own little profit from that, selling residence permits for five bucks a year.

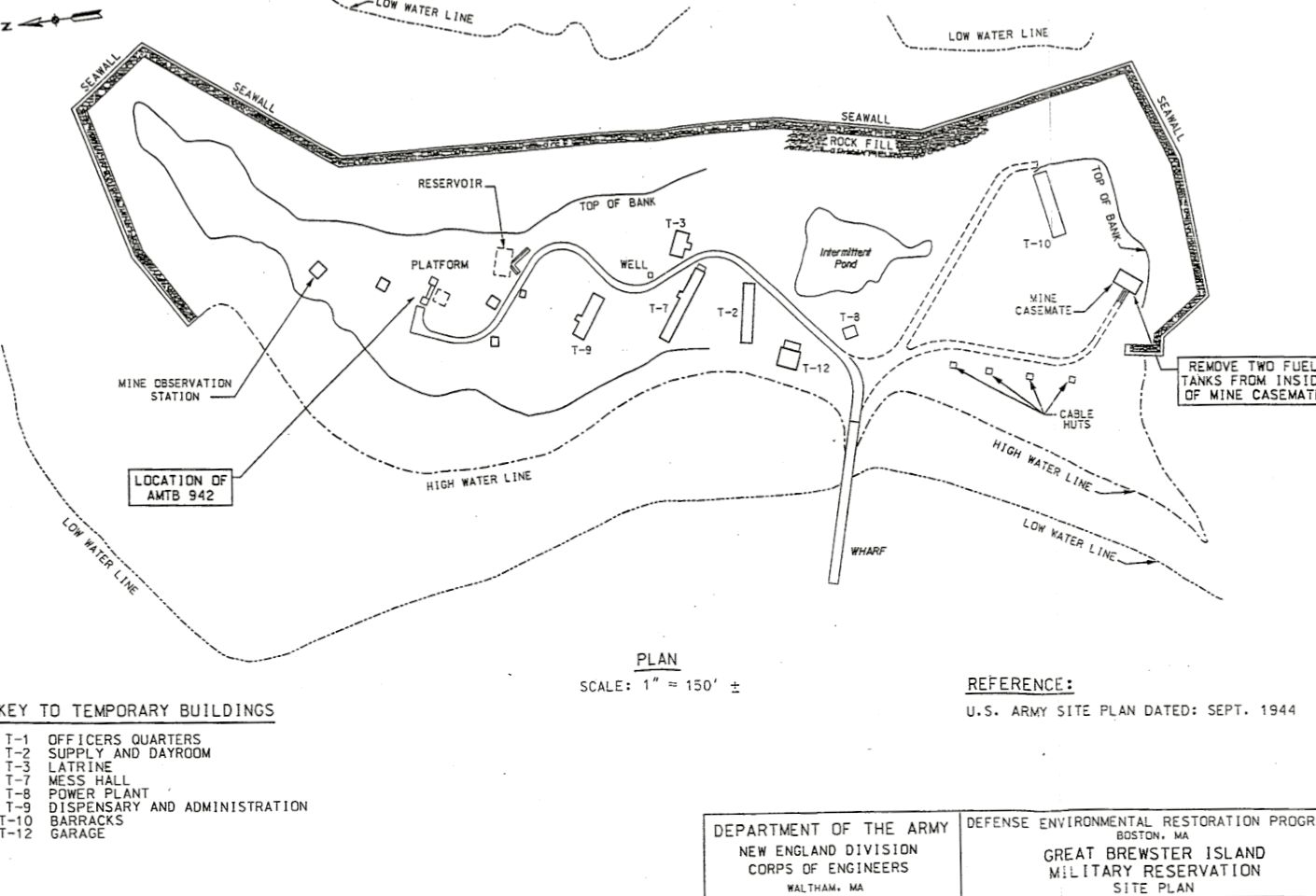

It all changed in 1941. The summer residents were (presumably) told to immediately vacate the island. Back then, Boston was seriously concerned about a potential German attack from the sea and from the air. As a part of Boston Harbor defense system, they built a mine observation post, a mine casemate and a 90mm gun battery on Great Brewster island.

If you need to know more about the battery, it had a dual mission of defense against fast enemy motor torpedo boats and enemy aircraft. The effective range of the guns was about 4.5 miles. Each weapon required a crew of 15.

And if you persist in your interest and want to know now how those fun toys looked, nothing remains of the battery on Great Brewster, so the following photo is not mine and not from there, but here is how:

The mine casemate was in a sense even more interesting. It was an underground control center for remote control (an euphemism for remote blasting, of course) of the mine fields in Boston Harbor. The Great Brewster casemate controlled 20 submerged mine groups, 19 mines each. Two other mine casemates were located on Georges Island and Deer Island.

In 1946 the military closed the shop, and 1953 the island was sold. Today it belongs to the state government.

A government-made map of the island from World War II (note that the north is to the left):

While I was telling you the island history, we have sailed towards the island, dropped the anchor, inflated our dinghy, rowed ashore and re landing on tne beach. We are not the first here,—there are a couple more boats anchored nearby, and we meet a few people on the island—but of course nothing compared to the crowds of Rainsford Island.

View from the anchorage (Boston Light is behind the island; before the island to the right you can see a small dinghy from another boat).

View back at the anchorage after the landing (our boat, the Funny Cigarettes, is in the middle):

The Drumlins

As you probably noticed, Great Brewster consists of two drumlins, glacial hills with one side steep and another gently sloping. Boston Harbor is, apparently, the only place in the world with drumlins turned islands, and that makes them special. As any other drumlins, they were made by a glacier, but then the wind and water kept hewing them out. Erosion affects virtually all of our islands; they constantly keep shrinking. (Here is an interesting map showing how Great Brewster kept changing between 1820 and 1851.)

A steep side of the northern drumlin:

Climbing the drumlin, just as on Rainsford Island, in a wild forest, we stumble upon two apple trees with some tasty apples.

That northern drumlin is the highest natural point in Boston Harbor: 105 feet (32 meters). (Spectacle Island is higher, but it is somewhat unnatural.)

That’s why when we finally climb there and arrive at the top, the views are great. Mostly towards Boston; other sides are overgrown with trees.

But here is a view to another side anyway, with some other outer islands:

While I am taking these photos, Sasha alerts me that I am standing on a cement platform floating in the air above that same 100-feet precipice. Here is how it looks from aside and from down below:

Maybe that’s some remains of the World War II observation post. Or maybe of the anti-ship battery. One would assume—hope—that they were not suspended in the air back then.

Enchanted Isle

Now I’d like to tell one interesting story about Great Brewster.

It starts (or, perhaps, ends) with one John Stilgoe, a professor in the History of Landscape in Harvard. One day he was traveling on his bike around Cape Anne, happened on a used bookstore, and just had to venture inside. There he found a hand-written diary from the late nineteenth century. Eventually, he arranged for one of Harvard libraries to acquire it, and this is where the diary resides since then.

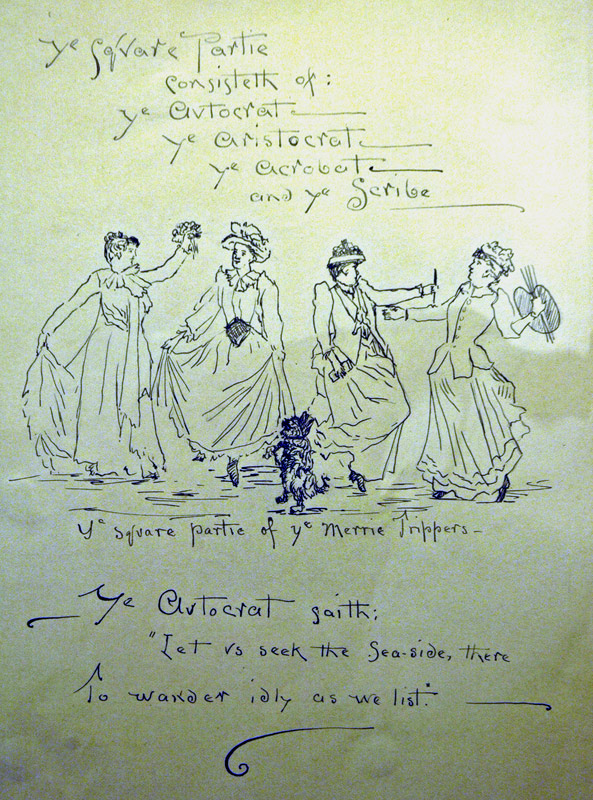

The story starts for real on July 15, 1891. Four well-to-do ladies hire “William the Swedish fisherman” to deliver them on his sailboat to Great Brewster—“an enchanted isle”, they call it. There, they rent a house, spend there two unforgettable weeks, and put in a diary everything that happens to them. The very diary that John Stilgoe has discovered. 58 pages of texts, drawings, watercolors and photos.

On the human level, I find this story quite fascinating. The ladies, far away from their families and their servants, live slow life. They walk around, cook meals, watch sunsets, read to each other. Keep a diary. Take a lot of photos. I would guess that photography was not an entirely trivial skill back in 1891.

Their diary is a real journal. Like “live journal”, only without quotes. And, just as in LiveJournal or a blog, they write under nicks, without using their real names.

Here they are, the four friends the way they saw themselves.

They called themselves the Autocrat, the Aristocrat, the Acrobat, and the Scribe (apparently, they ran out of “a” words by the fourth friend).

Historically speaking, of course, the journal provides a rare glimpse of that life, gone long ago. Of that harbor. Of that Great Brewster.

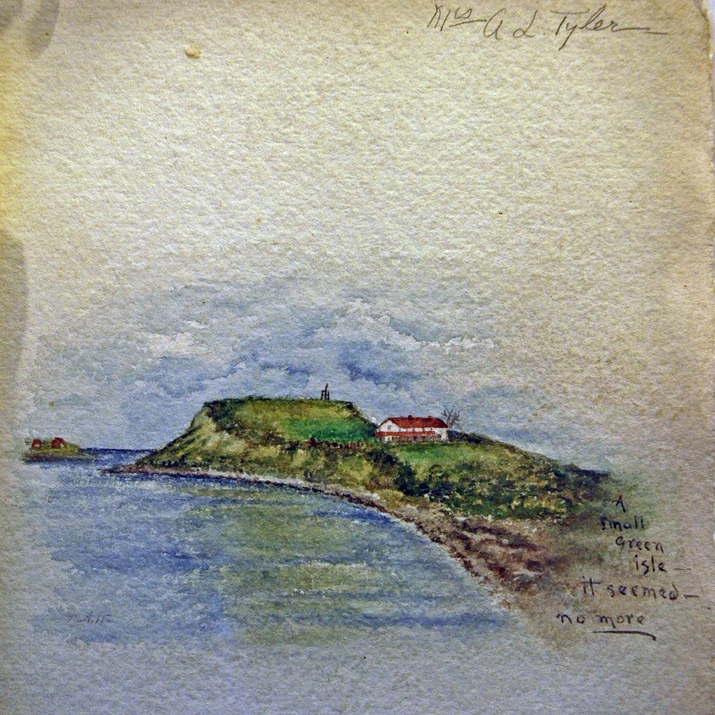

Bidding their farewell to the enchanted island, our ladies drew it on the last page of their journal:

“A small green isle—it seemed—no more.”

The cottage where they lived is, indeed, no more. No traces remain. Yet what does still remain on that same island?

For example, this crumbling seawall.

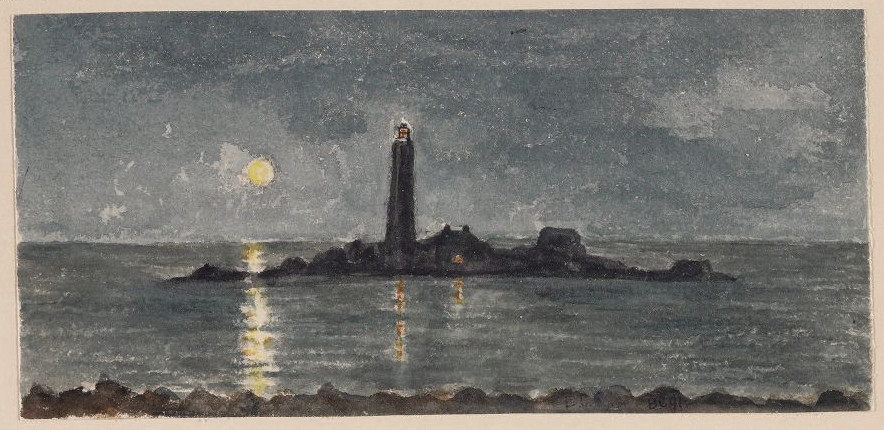

Or this nice view at the neighboring Little Brewster Island with Boston Light. The light keeper, by the way, would sail his boat over to visit our ladies—for no particular reason, just to chat and to find out what was going on.

For the sake of comparison—a similar view, but in 1891 and at night (from the journal):

The four ladies didn’t live in a particular solitude. The residents of other islands stopped by to visit. Passing-by ships picked up and delivered mail. The island itself was not uninhabited either. We know, at least, that the mysterious William the Swedish fisherman lived there. 115 years ago Great Brewster was way less wild and secluded than it is now. There was even a working well on the island (not anymore).

What we do have today more than back then is the views of Boston skyline:

This is, presumably, a foundation of one of the military structures from World War II. Maybe T-7 MESS HALL from the military map I showed before?

That particular foundation is situated in the middle of the island, between the drumlins. Nearby we find a shack with a weird set of items inside, and an empty frame with armchairs.

My guess is that after the state government bought the island and it got neglected (or, the other way around, after it got neglected and the government bought the island), they tried to make it into a slightly more organized park. Here is an undated photo from the internet which explains the original intent of the now-empty frame:

Wikipedia also has a photo with this sign, dated 2007.

Besides, we see other signs of neglect. Benches and fences in different stages of falling apart. Busted composting toilet, marked as working on the official website.

Apparently, the island has gone wild again. You explore it, and feel like archaeologist unearthing a cultural layer after a cultural layer.

And then you see those armchairs, and now feel like you are in a Dali painting. They were clearly brought from the mainland. Apparently, somebody has cared enough!

And one final request to you, my reader. If you or you friends want to visit Great Brewster Island, please don’t for William the Swedish fisherman. Just ask me. I’ll bring you over.

Time To Leave

It is time to wrap up the story of Great Brewster, the largest and the highest of all outer islands of Boston Harbor. Far away from everything that is near, near to everything that is far away. Having swallowed in its wildness the houses, and the forts, and the park signs. Standing guard on the border between the ocean and the continent. Equally beautiful from sea and from land.

We are standing now in the middle of the island, between the hills, where one can see fair views of the city of Boston and Boston Light behind the grass.

Each time, when exploring a new place, I am always glad when I couldn’t see everything I planned. It means that something tasty is left for a future visit.

On Greater Brewster we didn’t even start exploring the south drumlin. And yet, the remains of mine casemates should be there. Besides, somewhere on the island should be a pond, or swamp,—we missed that as well. Well, next time!

And you, my dear reader, to you I barely showed a tenth of beautiful photos from the island. Which is unfortunate, but remember that photographs are anyway powerless to convey the beauty of real life. Want to really see what kind of an island Great Brewster is—come join our next expedition.

Finally, a few artifacts found on the island, both natural and artificial:

And now the time has really come to say our good-byes to Great Brewster. Some rowing, and some swimming, we are coming back to our boat, to our Funny Cigarettes.

Last glance back. Farewell, Great Brewster! We’ve enjoyed spending time with you, and we’ll do our best ti be back. A small green isle—it seemed—no more.

Meanwhile, while we were exploring the island, a fresh breeze has built up. Did you see how the grass was swaying in the video?

And here, we raise our sails, weigh the anchor without turning the engine on, sail back to the green buoy No. 9 (looking back from time to time to make sure again that were are not being set by the current from the line between the buoy and the lighthouse) and set off to the new adventures.

Land is good, but the sea is even better.

And that is another story.

Subscribe via RSS