Castle Island

If you recall, I have a project: to visit all the islands of Boston Harbor, to explore them all, and to document for you.

At one point last January I got overwhelmed by the melancholy and gloom of so many months still remaining till the beginning of the season.

Winter, cold, darkness, gloom. No colors, no smells. Just a desperate desire to touch the tight sail full with wind, to inhale deeply the sharp smell of the sea.

Lacking all that at our Northern latitude, I boarded my two wheel vessel — my bike — and set out to explore Castle Island.

That was back in January. This November Jeremy and I have repeated that trip quite successfully. The following report generally follows my first, January exploration with a sprinkling of photos taken on the later trip, and also photos taken from the water during the past sailing season.

When Castle Island was still an island, not connected to the mainland, it was one the islands closest to Boston. These days one passes by it when leaving the inner Boston Harbor. That’s why the island appears often on photos taken by me and my crew.

For example, in this picture taken in 2012 by Talha the island is seen from inner Boston Harbor. To the right is HMS Dauntless, a British stealth guided missile destroyer, visiting Boston on the way home from her first mission (patrolling Falkland Islands).

And here is a picture from a slightly different angle, to the south of the shipping channel, with a landing plane grazing the fort, and a cruise ship going down the channel out of the Boston Harbor.

These days Castle Island is not an island anymore, just a part of Boston. In fact, it is no longer practical to get there by a boat. One reaches the island by car, by bus, and of course by bicycle. And so I went.

My route led me through downtown Boston, over a couple of canals, through the newly-fashionable high tech start-up neighborhood, the expo center, past the cruise ship terminal (last time I saw whole three ships there, this time none… off season, maybe?), past some weirdly-looking buildings behind barbed wire with signs “Wait for guard to gain entry”, and, finally, past the tall wall of the Port of Boston’s container terminal. Right behind the terminal our island had finally begun, — with a parking lot, as every self-respecting island does, — and behind the parking lot the fort walls were towering.

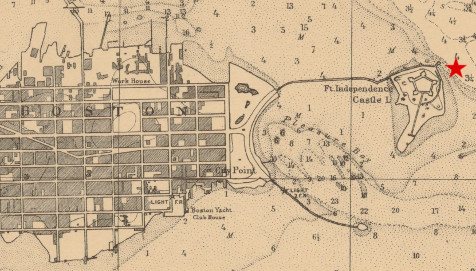

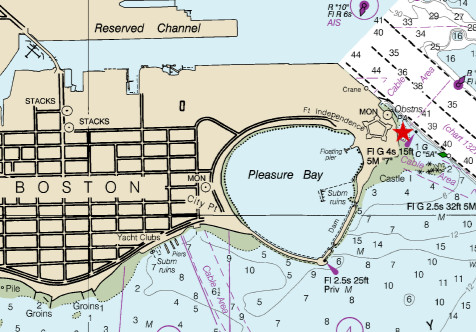

How does an island stop being an island? Here are the three charts showing its transformation.

First one is from year 1775. Castle Island is obviously an island. Note that even the mainland closest to it does not belong to Boston yet: it is in the separate town of Dorchester.

1896. Mainland has visibly grown and became a part of Boston (specifically, South Boston). A dam (or a bridge?) leads to Castle Island. Another dam goes from the mainland to the tiny piece of land called Head Island (to the south of Castle Island), not even labeled on the map because of its insignificance.

A modern chart. Castle Island is no longer an island, although it is still called such. The city has reached it and absorbed it. The dam from the city to Head Island is still there, and another dam was added: from Castle Island to Head Island.

Now, let’s talk about the fort. All the charts above show some kind of a defense structure on the island. It was first built in 1634, just four years after founding Boston.

The history of founding the fort relates the quaint simplicity of those early colonial times. In July 1634 a party of twenty people lead by the colonial governor visited Castle Island, and came to the agreement that it was a great location for a fortress. Everyone contributed on the spot five pounds towards the construction of fortifications, and that was it.

From who were the colonists going to defend Boston Harbor? Unlikely that it were Indians. I suspect that even then they understood that the greatest danger for the British colony was the mother country herself.

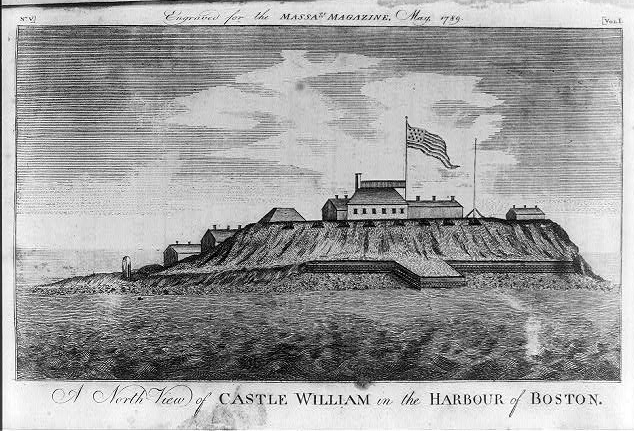

The original fort (then called just the Castle) was rebuilt multiple times. Its incarnation built in 1701 was called Castle William — after the English King William III, also known as William of Orange.

I could not understand whether the name “Castle Island” precedes building the forts-castles on the island, or was given because of them: I found contradictory claims in the literature.

Castle Island played an indirect role in the American Revolution. In March 1770 the so called Boston Massacre took place: clashes of civilian colonist masses with armed British troops led to death of a few colonists. The situation in the city became extremely volatile; to avoid further bloodshed, the government was forced to evacuate the troops from Boston to Castle Island. Boston Massacre was the first in the chain of events that led to the revolution (Boston Tea Party; blockade of Boston Harbor; making all stops thereafter).

As we all know, the revolution had won. In March 1776 the British evacuated from Boston and Boston Harbor. As a parting gift, they set to fire Castle William (and also Boston Light).

After the revolution the fort was rebuilt and renamed. Obviously, it could not bear the name of an old-regime king anymore. Something more patriotic and inspirational was needed: Fort Independence.

Since then, the fort had not engaged in any hostilities. The peace time life of fortresses is inevitably boring, so I would mention just one interesting episode. In 1827 the eighteen-year-old writer and poet Edgar Allen Poe had served in the fort. While there, he heard a legend of the duel that had taken place in the fort between two officers: one popular and one unpopular. The unpopular officer killed the popular one, and his comrades took a revenge by bricking him up alive in the fort dungeons. This story inspired Poe to write one of his most well known short stories, “The Cask of Amontillado”. Wikipedia claims that the legend is factually wrong: the duel did in fact take place, but the winner was never sealed in a dungeon. Needless to say, nobody should trust Wikipedia in the first place.

In 1890 the federal government transferred the fort and the island to the City of Boston, but later was taking it back for every new war. There were at least three such wars since then: Spanish–American War (1898), World War I and War World II. During World War II, the fort housed one of the harbor defense command posts, and also a degaussing station. Such stations removed magnetic field charge from the ship hulls to decrease the probability of a naval mine going off.

After World War II the fort was never used militarily again. The space around it became a park. So we are going to skip right to January 2017 and to see what I saw when I arrived to the island.

To my disappointment, the fort gates turned out to be locked. It is open for visits on summer weekends: turns out I came off season! Alas, the fort still remains not explored from inside. We will have to come back again, in the summer.

On a nice summer day, it is always crowded here, but now I see just a couple of people.

Close-up of the cannons pointed towards the shipping channel.

The remains of an old dock. Now it is no longer possible to dock at the island; we have to arrive by bike.

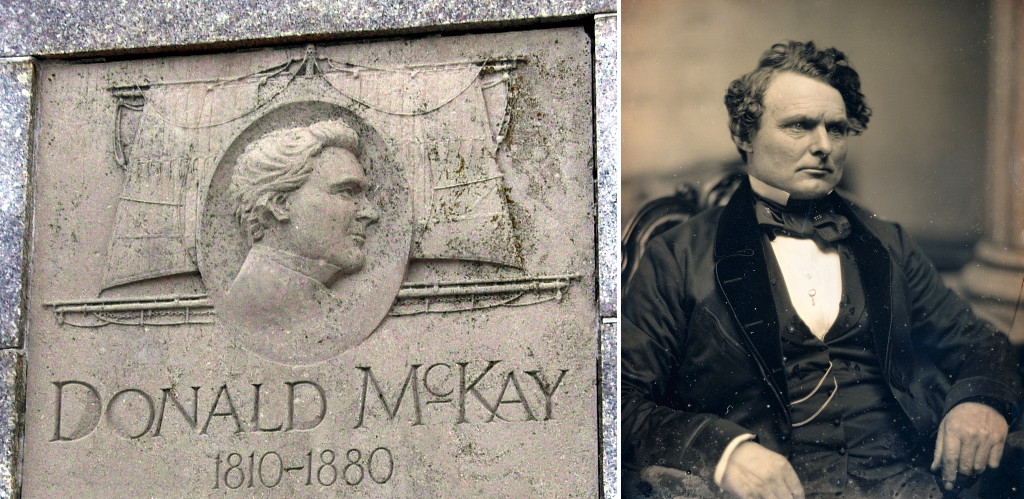

There are a few memorials on Castle Islands. The most important and the most visible of them is a stone obelisk commemorating the great Boston shipbuilder Donald McKay (1801–1880). It stands in front of the fort and is readily visible from the shipping channel (see, for example, the first photo above).

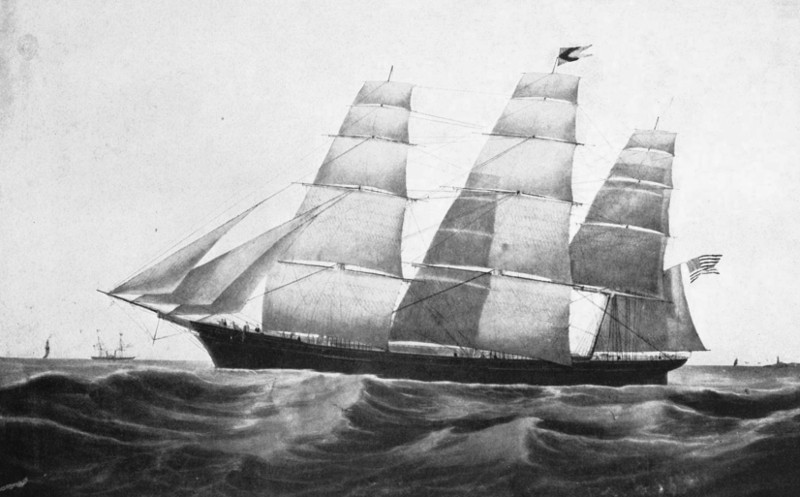

Over his career McKay built over thirty ships, mostly clippers. They are all listed on the memorial pillar. McKay’s clipper were among the best in the world. Here are a few of them.

The Great Republic (1853) — the largest clipper ship ever built.

The clipper Flying Cloud (1851) set the world record for the fastest passage from New York to San Francisco (89 days 8 hours; obviously that was before the Panama Canal).

The clipper Sovereign Of The Seas (1852) set the world speed record for sailing vessels: 22 knots (25 mph). She was the first ship ever to cover over 400 nautical miles in 24 hours.

McKay’s shipyard was located across the channel, in East Boston; he lived in the same neighborhood. It feels right that his Castle Island memorial stands right on the shore, and all Boston-bound vessels pass by it.

(Parenthetical note: back in October we went on a walk in East Boston, and what do we see? This large size rendering of the Flying Cloud, set to the background of a working shipyard.

Donald McKay is not forgotten in Boston.)

On the chart above, you might have noticed Pleasure Bay, the artificial bay almost entirely surrounded by the dams from the city to Head Island, and from Head Island to Castle Island. In the summer, the city part of the bay has a popular beach with relatively warm water.

It is an ebb tide now; the ocean is rapidly escaping the bay throw a narrow opening in the dam. The barely perceptible smell of the sea breaks though the sterile depression of Boston winter.

A detail of the coastline.

Meanwhile, Jeremy is shooting gulls.

This pavilion with a weather station takes a large part of Head Island, a tiny parcel of land connected by dams to South Boston and to Castle Island.

Same Head Island as seen from the water in early October. Clearly, those were happier times — or at least sunnier times.

The view towards Boston. In the background, left to right: the Prudential and the Hancock towers, the two tallest Boston buildings; financial district; containers and cranes of the Port of Boston’s Conley Container Terminal. The port authorities have to get an approval from FAA for every new crane purchase: the terminal is below the landing approach to Logan Airport, and the planes fly really low here.

Same containers, behind a wall as seen from the island.

The landing planes fly really low here.

As you can see, there is a lively traffic around Castle Island. Planes, container ships, cruise ships. Yes, January is off season, but otherwise it feels like Boston is getting more and more popular as a cruising stop. As I mentioned before, I would oftentimes see three large cruise ships docked simultaneously at the cruise terminal just a few blocks away from here:

But with all this traffic, one thing is very conspicuously missing: cars.

Jeremy, for whom it was a first visit to a Boston Harbor island, felt it strongly: the feeling of quietness, slowness, otherwordliness.

Castle Island is, arguably, the least of an island out of all the islands in Boston Harbor. It is an actual part of Boston, easily reachable by car and by bus. It is not even a part of the Boston Harbor Island Park Area!

But despite all that, the island magic is still going strong. And, for Castle Island, feeling the magic does not even require a boat: just come here, lean your bike against a fence, step across the invisible line and get lost in a different world.

We are coming back from our walk down the dam to Head Island.

An emergency call button (in the blue pillar) is powered by the wind and the sun.

The cold winter sun is setting behind Fort Independence.

The sun has actually set. It got dark and cold. I mounted my bike and headed home, to count days till the next sailing season.

I am leaving you with the photo which I took back in the same January from a plane landing at Logan over the container cranes. On it, you could easily see the pentagon shape of the fort. Castle Island itself is bounded by the port terminal wall to the left, the parking lot at the bottom, and by the dam extending to the right.

Subscribe via RSS