Outer Brewster Island

As this sailing season is rushing to the end — (Beautiful moment, do not pass away! Whither are you speeding to? Answer me. No answer.) — I thought it made sense to remember the last sail of the previous, 2016 season.

Such is my custom: on the last Sunday of the season — the last Sunday in October — I gather my comrades in arms for a farewell sail. To end the season the fitting way, with an exclamation point and not with an ellipsis.

Last year, my faithful comrades were Ryan, Sergey and Andrew. We departed from the mooring; the weather was great: it was unexpectedly and unseasonably warm; but the weather was also not that great: there was little wind. Virtually no wind, in fact.

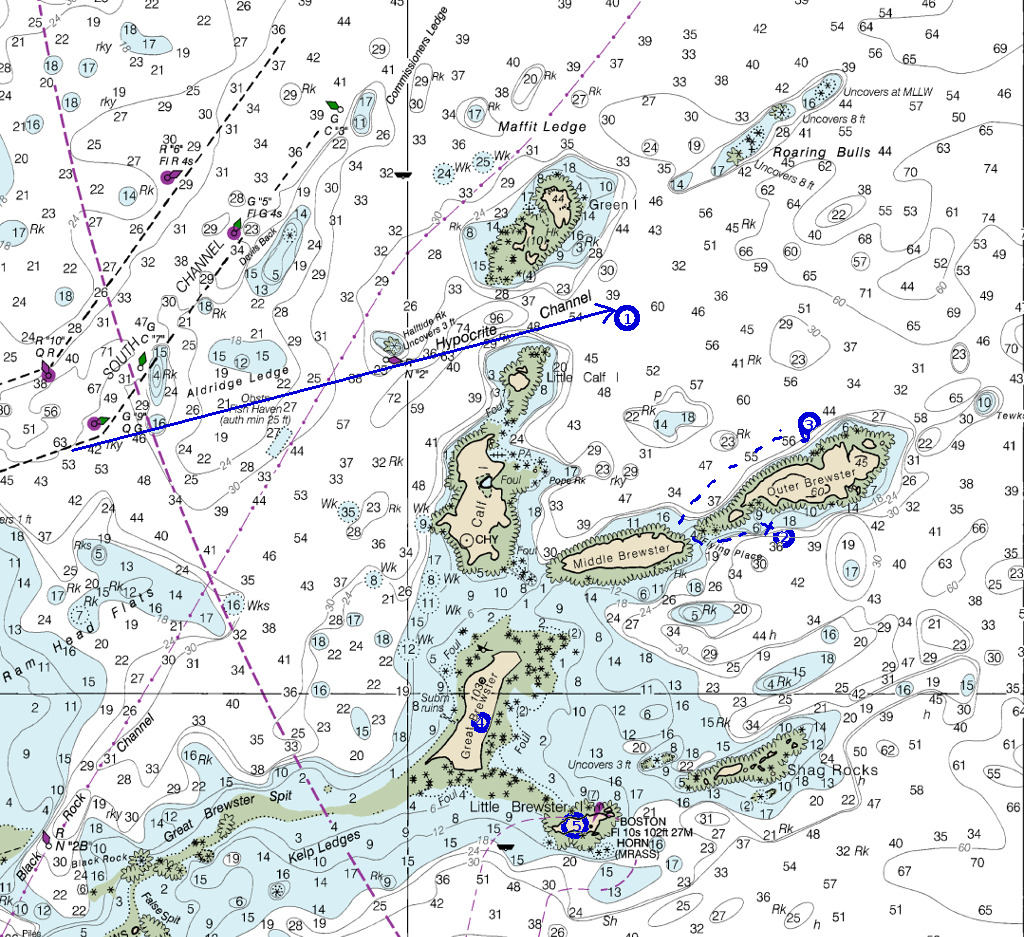

For that case, I had a plan B in my head. We turned the engine on, and under the power went to explore Outer Brewster Island, a very interesting island where we have never been before.

Outer Brewster belongs to the group of outer islands in Boston Harbor that sometimes are called just the Brewsters. One of them, Great Brewster Island, we explored the year before. Just like it, Outer Brewster is called by the name of its former owner William Brewster (ca. 1566–1644), the elder and spiritual leader of the Pilgrims, who came to the New World in 1620 on the Mayflower.

I can’t resist the urge to show you again the reconstructed portrait of this stern Puritan in a yarmulke.

All the outer islands share the same distinct character, stern and lonesome, a perfect match for the Puritan founding fathers. They take upon themselves all the might of the Atlantic Ocean, protecting from it the city and the harbor. And out of all of them, Outer Brewster is the furthest, sticking out the most into the ocean.

The easternmost point of the City of Boston. The easternmost piece of land.

Beyond it, if one just keeps going, is a three week Atlantic crossing and the Azores.

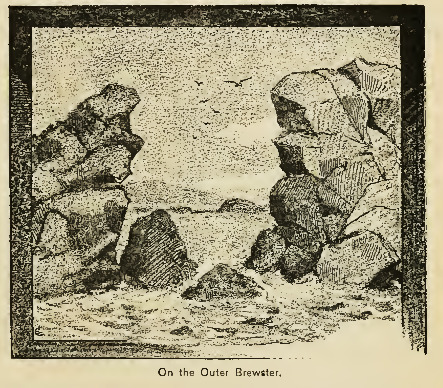

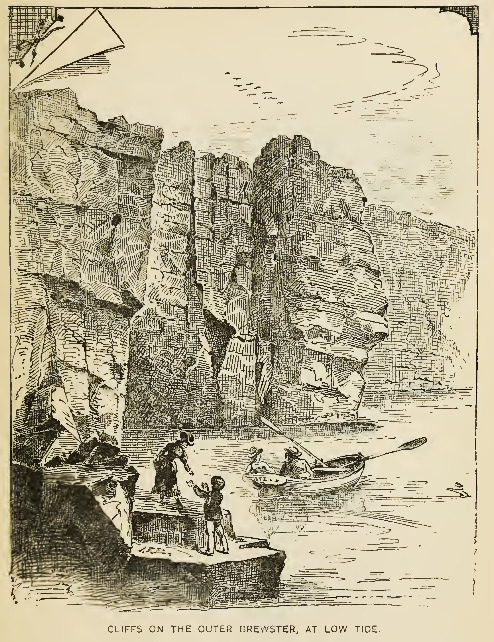

Experts have been praising Outer Brewster for long time. Edward Rowe Snow, island and lighthouse historian: “Outer Brewster Island is, perhaps, the prettiest of all the islands of Boston Harbor. A day spent at this site of chasms and caves will never be forgotten by the visitor.” (*) Dr. Nathaniel Shurtleff (1810–1874), politician and Mayor of Boston: “This island is one of the most romantic places near Boston, far surpassing Nahant in its wild rocks, chasms, caves, and overhanging cliffs.” (*)

King’s Handbook of Boston Harbor (1888) illustrates it for us:

Outer Brewster Island is too small and too remote to have any rich history associated with it. When it was inhabited, it was mostly by some weird hermit characters. There were a few exceptions, though.

In 1799 one Austin bought a part of Outer Brewster, and we know that the entire island was worth 400 dollars at the time. Later on, in the nineteenth century it was fully owned by the Austin family, who tried to use it as a quarry. In Boston there remain today at least two buildings built with stone from Outer Brewster. Luckily, the family business fizzled out, or they would’ve taken apart the entire island.

During the World War II the island housed Battery Jewell, which consisted of two 6″ T2-M1 rapid fire guns connected by earth-covered reinforced concrete magazine and fire control, and a number of other buildings and structures, including a radar and a water distillation plant.

These bad boys “fired a 105 pound armor-piercing projectile with a range of over 15 miles at a rate of up to 5 rounds per minute” (FortWiki). On the nearby Great Brewster island there were different pieces of artillery, coordinated with Battery Jewel.

The T2-M1 guns are long gone from the island. Only 6 of them still remain in the world. At least we know what they looked like:

The garrison on Outer Brewster numbered 125 men. They didn’t take part in fighting: the enemy did not attack Boston, neither by water not by air. (With the notable exception of German submarines who were quite active in these parts. But that’s a different story.) The battery was installed by January 1944, and deactivated soon thereafter, in 1947. Eventually the island was transferred from the federal government to the state and became a part of Boston Harbor Island Park Area.

That would mean that the island was safe, right? Wrong! In 2005 the energy conglomerate AES Corporation, one of the world’s largest power companies, put together a proposal to build an LNG (liquefied natural gas) terminal on the island. From time to time natural gas is transported to Boston by LNG tankers, and so they had decided to build a five-hundred-million terminal on Outer Brewster. When you have some extra five hundred million dollars lying around, you need to do something about them, rather than just keep them under the pillow. Right?

Moreover, when you have some extra five hundred million dollars, you might as well spend some pocket change on lobbying. A bill was introduce in the state legislature which was written in a way to disqualify all other companies but AES. As is customary, a proper propaganda campaign was launched. The Boston Herald, one of the two leading Boston newspapers, derided the island as “an outhouse for gulls”.

And then a miracle happened: the people resisted. Go figure! Who could be concerned by the fate of a remote, barely accessible island? But the resistance had shaken the resolve of the lawmakers to pass the corrupt bill. In 2007 AES gave up, withdrew its proposal and left to spend its millions elsewhere. The good (temporarily?) defeated the evil. Outer Brewster remained in its beautiful desolation.

At that — specifically, at the beautiful desolation — we pause our historical lesson and jump forward to October 30, 2016 as the crew of the sailing vessel Funny Cigarettes is planning landing on Outer Brewster: for exploration purposes, yes, but also to drink up a bottle of bourbon and to celebrate the end of the season.

To land on this island is not straightforward, especially if you operate from a keel boat. First, we have to find a good spot to drop an anchor — there is only one suitable place — convince ourselves that the wind and the waves are favorable for anchoring — this is indeed the outermost island, fully exposed to the ocean from the west.

Then we pump up our rubber dinghy, and start rowing around looking for a good landing spot, a good beachhead. The beach that I mentally selected on Google Maps satellite photos is entirely under water (high tide!); the island coastline consists of steep cliffs and sharp rocks, exactly as promised in nineteenth century quotes and drawings.

We have to round half the island until we find a small, rocky beach to beach our dinghy.

Landing on a new island — and especially on a uninhabited, not-a-single-soul-there island — always fills my heart with certain trepidation, certain anticipation of new discoveries.

And this little scrap of land, sticking out into the Atlantic Ocean, overgrown with shrubs and thorns, with military buildings falling apart, from whose rooftops one can see wide views of the nearby islands and lighthouses, and of the distant Boston skyscrapers, and by the way, some good man has left a ladder, using which it is possible to climb to the roof, the world is indeed not without good people, with all these rocks and cliffs frequented by birds, with deep chasms between them, this island is certainly good on its own, but how much better is it made by the remoteness, by the desolation, by the emptiness, by the challenge of the landing, by the sweet taste of the adventure.

Slanting sunbeams burst open from behind the clouds and illuminate the neighboring lighthouses — Boston Light to the south and Graves Light to the north — and our sweet girl, the sailing yacht Funny Cigarettes riding on the anchor. The early autumn night is coming closer and closer; it is time to go home. We get into the dinghy and unanimously decide to round the island from the other side, completing the circle. And again cliffs, birds, the swell breaking loudly on the rocks on one side — and the boundless ocean on the other side.

Oh Outer Brewster! You are so beautiful. Snow and Shurtleff were right. Thank you for hosting us this last day of the season and making an unremarkable sailing outing into an exciting exploration.

Good bye, new friend. Winter well.

We will be back.

Of course, one can’t write a report on an island without photos! Here come a few photos for you.

Outer Brewster is a low and squat island; it is hard to take its picture from the water that would be impressive. Here are a few views of the island as we were rounding it on the sailboat.

Our beachhead. Graves Light is seen in the distance.

The promised cliffs and chasms. Some good people put a board over the chasm. (We didn’t walk it.)

The guns are (unfortunately) long gone, but their mounting points remain.

The bunker entrance between the guns. Here you can see a standard layout of a battery like Outer Brewster’s.

Next time we’ll have to explore those dungeons of the twentieth century much more thoroughly.

Local flora.

Sergey is happy to have arrived to Outer Brewster.

Other good people put a ladder here, and we used it to climb to the roof of one of the remaining buildings of the military base. A view to harbor islands and the distant Boston. If you squint your eyes and look really carefully, you even see cruise ships at the dock.

The Funny Cigarettes, patiently waiting for us at the anchor, and Boston Light on Little Brewster Island (view from the roof).

One more view of the lighthouse and the Funny Cigarettes, since it represents that day so well. No one else is in the harbor. The world belongs to us. Just extend your hand and take it.

For a good measure, Boston Light itself.

An epic panorama that Sergey shot before we left (and much larger version — for much more detailed viewing). Left to right: I (in the bushes), Middle Brewster Island (in the bushes), Calf Island, Green Island, Graves Light.

We go around the outer part of the island in our dinghy, and head back to the sailboat. The spiteful slander in the Boston Herald calling Outer Brewster “an outhouse for gulls” was in fact not so far from the truth. Except that, according to Wikipedia, not only gulls live on the island, but also cormorants, common eider ducks, glossy ibis and American oystercatchers.

As I sit on the dinghy bow and take pictures, the sailors, enthusiastically working the oars, row closer and closer to our faithful girlfriend, the old good Funny Cigarettes. Out exploration of Outer Brewster is coming to an end. Indeed, just two or three hours are left in this season.

We make our way back in the thickening dusk, and it is still warm, and rum flows, and it still feels great, and beautiful, and romantic, though certainly bittersweet, — even though there is still no wind, and we go under power.

Then, as we reach the airport, and it gets really dark and starts to rain, — at that moment our friends in the heavens flip the switch, a very pleasant breeze comes to being, we kill the engine, the boat stretches her sails like wings, and we fly for this last half hour to the mooring.

And this becomes that season’s end.

Subscribe via RSS