Georges Island

One day in September we were meandering around in Boston Harbor under sail. In the boat with me were my esteemed Father, who had just come over from Moscow to visit us, and was looking for new experiences, and Sergey, who had graciously agreed to help us with sail handling.

The wind died on us; big wake waves were making the boat uncomfortable; it was clearly the time to land on an island and go explore it; something Father does not get enough of in Moscow.

I spread the chart and started looking for an interesting island to go to, preferably somewhere I’ve never been before. You can bet I have a list in mind!

While talking to the crew, however, I learned that neither of them have ever been on Georges Island! That was hard to believe, especially for somebody who lived in Boston for many years. Georges Island — one of the most interesting for casual exploration islands in the harbor, feathering a well-preserved fort, great views and even restrooms and some food for sale. It is also easily accessible by a ferry… not to mention a sailboat.

Since we were stuck by Long Island, and Georges was practically around the corner, I turned the engine on and took my crew to the island.

Myself, I’ve been to Georges many times, most recently two years ago when the company where I worked back then had a summer party on an island. Most people took a company-chartered ferry to the island, but I offered to take anyone willing with me on a sailboat. To my surprise, 24 people signed up. We ended up taking two largest boats in the club, two Cal 39s, and mooring them off the island:

Over last winter all the island moorings have disappeared, so we had to anchor. That was tricky because of the nature of the bottom: it gets deep really quickly, so one has to stay close to the shore, and then make allowances for the coming tide and for the fact that the wind can change and start blowing onshore. And of course the best spots were taken by two sail boats already there.

So we somehow tucked ourselves in to the left of them, closer to a channel between islands (also not good!), I chose to hope for the wind not changing, and we set off to explore the island.

Let us too, my reader, go exploring! To help us get oriented, here is a photo of the entire island, as seen from the top of the hill at neighboring Rainsford Island. (We’ve anchored to the left of the dock, probably at the level of the leftmost sailboat on the photo, or maybe even further to the left.)

The original island name was Pemberton’s Island, after one James Pemberton, who owned the island and once, when his ownership was challenged, produced a prove at the court that he had come to the island two years before the Puritans arrived, and and had been living there ever since. By 1710, the island was called George’s for a prominent Boston merchant and selectman John George, — apparently the same John George who, representing the business community of the city, petitioned Massachusetts authorities in 1713 for

Erecting of a Light Hous & Lanthorn on some Head Land at the Entrance to the Harbour of Boston for the Direction of Ships & Vessels in the Night Time bound into the said Harbour.

(The lighthouse was approved, funded, built and went into operation in less than three years after that. It was, of course, the nearby Boston Light, the first lighthouse in North America.)

One Frederick W. A. S. Brown wrote a poem about Georges Island after his visit there in 1819.

(It goes on and on from here, and is a part of his much larger poem about Boston Harbor, A Valedictory Poem.)

Apparently at his time there were some buildings there, some facilities for passing ships and for vacationers.

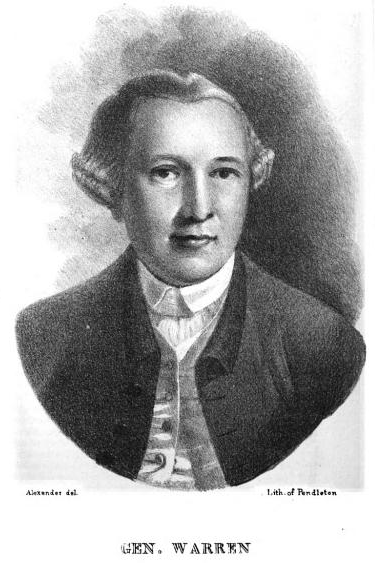

This is all well forgotten now, though, because in 1826 the federal government started the preparations to build a fort on the island; a fort that would take almost the entire island and from that moment on define its character. The actual construction began in 1833. The new fort was called Fort Warren after the revolutionary hero Dr. Joseph Warren (1741–1775).

Edward Rowe Snow quotes writer Peter Peregrine, who sailed by Fort Warren, which had been then being constructed for five years, and produced such a majestic description of the future fort that I have to repeat it here:

… Ocean Thermopylae, where a small band of Boston Yankees would as triumphantly beat back the navy of Great Britain as did the “Immortal Three Hundred” the myriads of Xerxes.

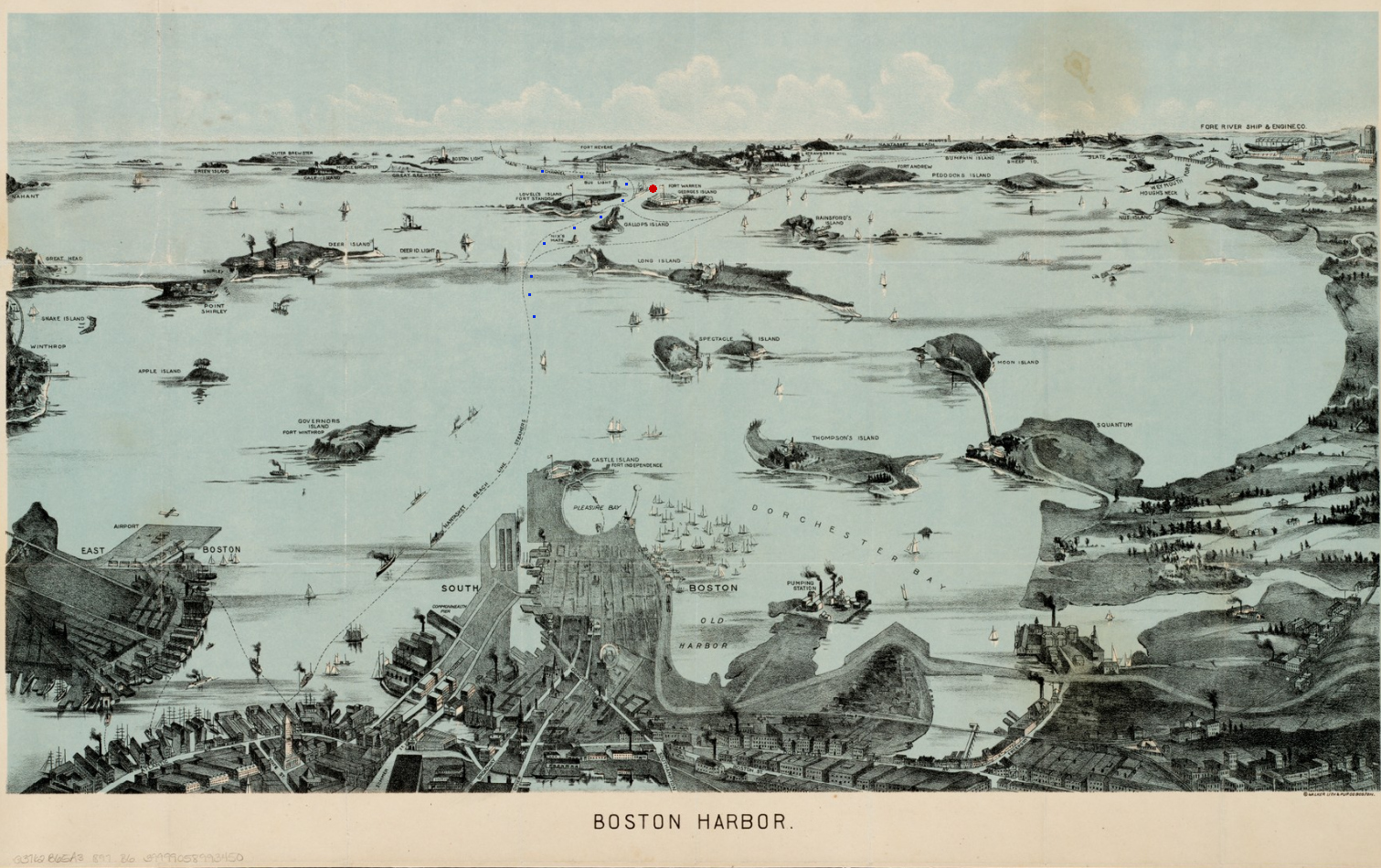

These days, sailing around in Boston Harbor, or even just looking at a chart or a map it is not even clear why would anyone build a fort there at all. Georges Island looks like a pretty random place in the harbor, far from the main shipping channel (which goes to the north of it, past Deer Island). Peter Peregrine with his Thermopylae sounds completely ridiculous.

However, the northern approach to Boston Harbor (past the Graves and Deer Island) was dredged and available to large ships only in the very beginning of the last century. Curiously enough, the following schematic view of Boston Harbor, published in 1923 or so, still depicts the main channel going between Georges and Lovells islands. (The picture is clickable, just as all others; you can explore it here by zooming even more.)

Actually, there are many interesting details on that “map”, like the size of the airport; we will explore them in the future posts in this blog.

What is important for us right now is that the main shipping route, the only one deep enough for large ships, for centuries did go between Lovells Island on one side and Gallops and Georges islands on the other side. The channel between those islands is still called The Narrows on a modern chart, and for a reason: it is about one thousand feet (320 meters) wide. In this context, the comparison with Thermopylae looks now spot on: a fort on Georges could easily control the flow of ships in and out of Boston Harbor.

The Army engineer in command the fort construction was Colonel Sylvanus Thayer (1785–1872), also known as “the Father of West Point”, a native of Braintree, Massachusetts. And, as we’ve mentioned before in the story of Peddocks Island, George Leonard Andrews (in whose honor Fort Andrews on Peddocks Island is named) in 1851–1854 served as an assistant to Sylvanus Thayer.

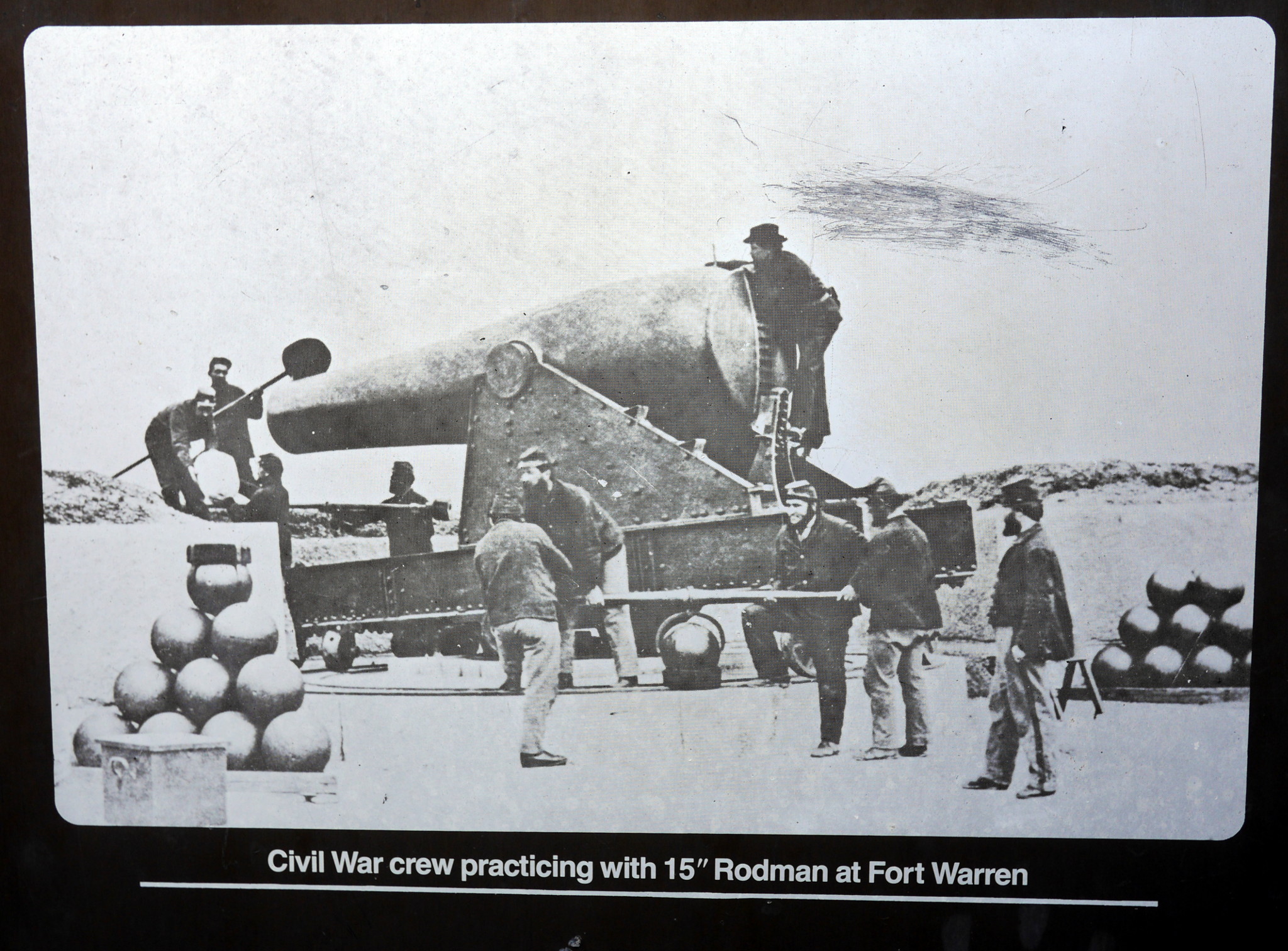

Most of the Boston Harbor islands have a specific period of fame, for which they are mostly remembered. For Georges Island, it is the Civil War. By the time when it began in 1861, the fort construction was kind of, sort of finished, but not quite: the soldiers that arrived to hold the fort, as it were, were immediately forced to start removing the construction debris from the parade grounds; there was only one gun installed in the fort, and even that lacked ammunition.

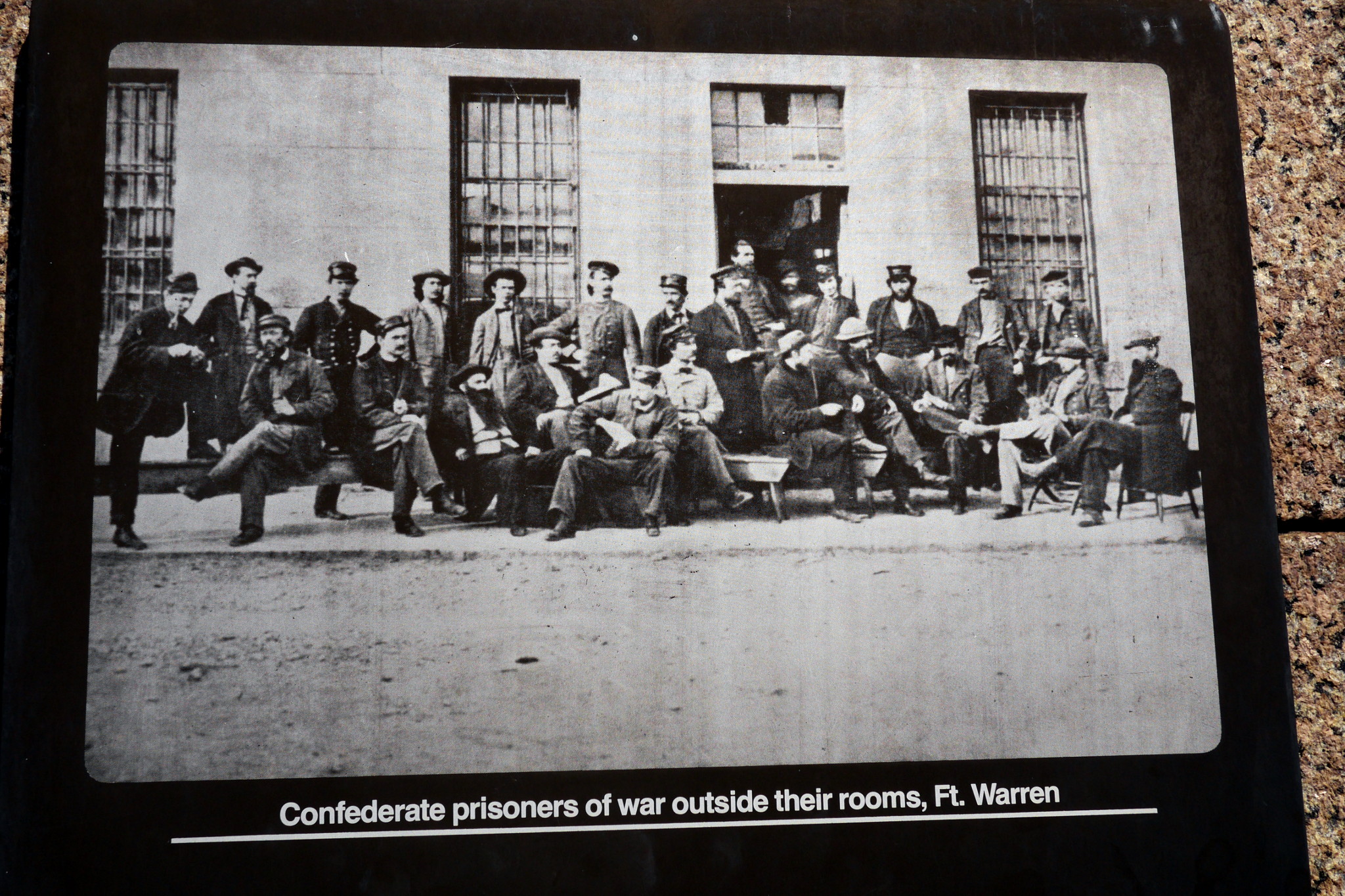

If the Confederate navy were to attack Boston (as was feared), the fort would hardly be able to put any meaningful resistance. The attack didn’t happen, though. Instead, Fort Warren became a prison for Southern prisoners.

Commanding the fort back then was this imposing gentleman, a veteran of the Mexican War, Colonel Justin Dimmick (alternative spelling: Dimick).

Colonel Dimick made a great effort to make sure that the prisoners were comfortable and well taken care of. Originally, when the war began, he was told to expect 150 people. When the boat with prisoners came, he discovered, to his surprise and shock, that it had over 800 souls! Colonel Dimick personally apologized to them for not being ready, and personally set off to Boston to procure food, blankets, and other necessities. Throughout the war, Fort Warren prisoners appreciated his care, and spoke highly of him afterwards.

Jay Schmidt in his book Fort Warren (which I bought in the gift shop on Georges Island) meticulously lists the states from where the prisoners came: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, West Virginia. Now, that’s quite a list! I am sure the local board of tourism was jealous.

There were two kind of prisoners: military (prisoners of war), and political prisoners, the Confederate officials arrested and sent to the fort without any trial. Apparently, the Constitution and the Bill of Rights were suspended during the war. King’s Handbook of Boston Harbor (1888) tells one story with such a simple naivete that I have to quote it verbatim:

The most serious attack upon the fortress was made by minions of the law from Boston, bringing a writ of habeas corpus to release a political prisoner. Being refused passage on the Government steamboat, they hired a sailboat, and approached the island, to find a detachment of the garrison on the wharf, under arms, and compelling the legal invaders to keep off and return to town empty-handed.

The list of famous Confederate prisoners held in Fort Warren is long, and quite boring for somebody as clueless about American history in general, and Civil War in particular, as I am.

So I’ll mention just a couple of most interesting cases.

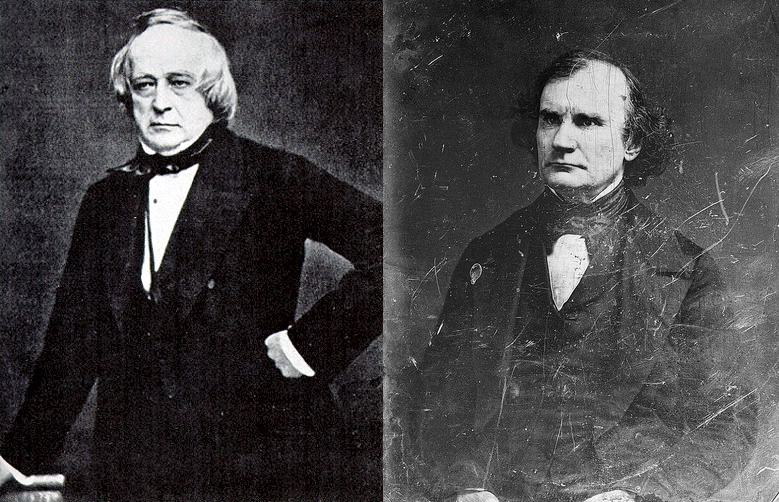

One has to do with the so called Trent Affair. The major war strategy of the South was to gain political and military support of Europe. To that end, confederate president Jefferson Davis has dispatched two distinguished gentlemen, James Mason and John Slidell, to England and France. Here they are, a sweet-looking couple.

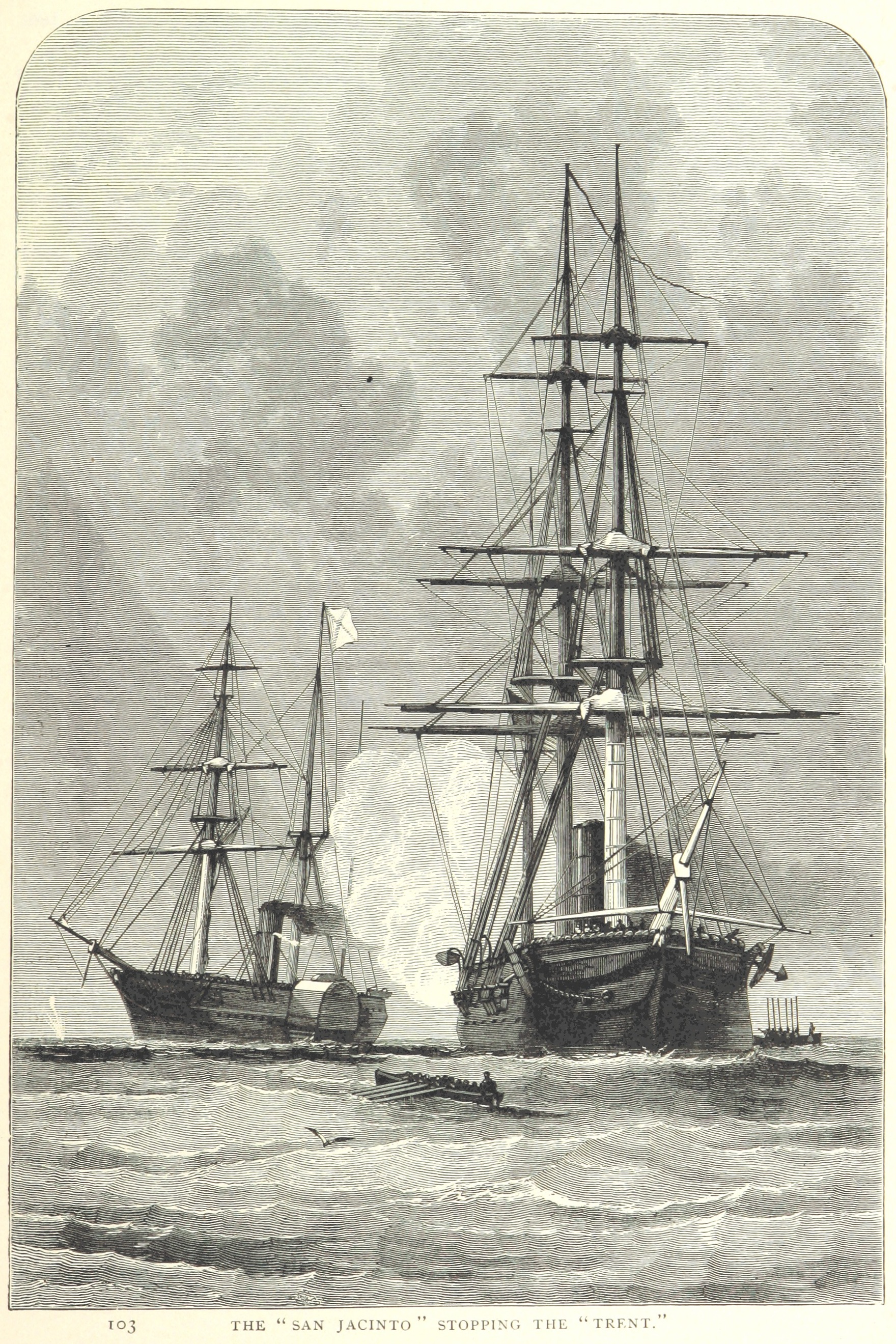

The couple sailed from Charleston on October 21, 1861 on a blockade runner and eventually arrived to Cuba, where they booked a passage on the British mail steamer Trent. In November, she was intercepted by the Union steam frigate San Jacinto in the Bahama Channel. Captain Charles Wilkes believed that he had the right to stop vessels in neutral waters and search for contraband. The radio has not been invented yet, so he could not check with his superiors; but even if he could, it’s not clear to me if the outcome would be different.

Anyhow, Captain Wilkes took the full responsibility for initiating an international crisis. A boarding party has boarded the Trent and forcefully removed Mason and Slidell, along with their secretaries, and transferred them to the San Jacinto.

They arrived in Hampton Roads, Virginia on November 15 and waited for the further orders from Washington. The orders came right away: set sail to Boston. On November 24 the unfortunate Confederate diplomats and their equally unfortunate secretaries were securely installed in Fort Warren. Captain Wilkes then proceeded to Boston “to receive the promised ovation” (from a witness diary).

The British were furious, and reacted the way the United States would react today in similar circumstances. A diplomatic ultimatum was supported by the troops buildup in Canada and the Navy show of force.

President Lincoln didn’t enjoy the idea of opening a second front. On January 1 next year the prisoners were quietly released from From Warren and taken to Provincetown by a tugboat. There, “in a raging snowstorm”, they boarded a British sloop and finally sailed to Britain. The diplomatic crisis was averted, though the extra British troops had already deployed and remained in Canada.

What happened later is very educational: nothing. Mason met with the British Cabinet, and was treated with indifference. Slidell met with Napoleon III, with the exactly same result.

All of the commotion: the daring action of Captain Wilkes on high seas; the imprisonment; the diplomatic crisis; the geopolitical military maneuvers; the yielding of the President of the United States to that blackmail; — all of that did not matter at all. Drawing a lesson from that is left as an exercise for the reader; but it is important for us that Georges Island and Fort Warren played an important part in this high-stakes, much-ado-about-nothing drama.

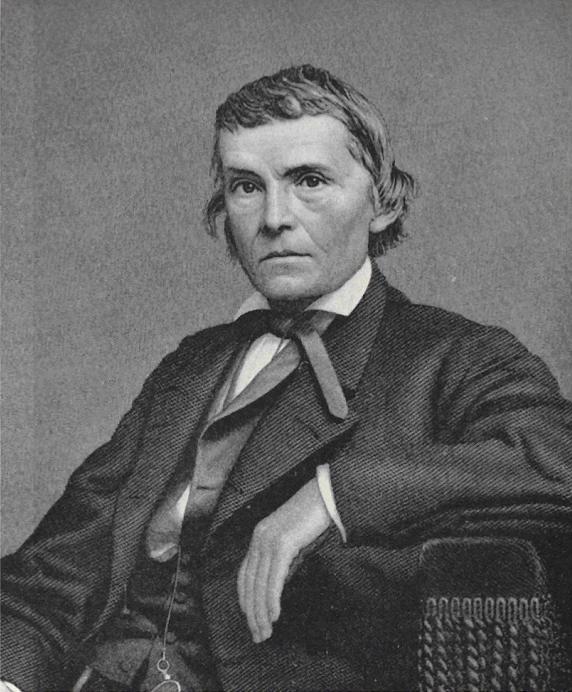

Another high profile prisoner, this time towards the end of the war, was Alexander Stevens, the Confederate vice president.

Stevens was arrested on May 11, 1865 at his home in Georgia, and brought to Fort Warren on May 25. He kept a diary while at the fort, last reprinted in 1998.

His diary provides a curious window into the way Fort Warren looked and operated back then, and also into his own mental state. Here he is brought to the fort:

I was alone, a coal fire was burning; a table and chair were in the centre; a narrow, iron, bunk-like bedstead with mattress and covering was in a corner. The floor was stone — large square blocks. The door was locked. For the first time in my life I had the full realization of being a prisoner. I was alone.

And then three days later:

The horrors of imprisonment, close confinement, no one to see or to talk to, with the reflection of being cut off for I know not how long — perhaps forever — from communication with dear ones at home, are beyond description. Words utterly fail to express the soul’s anguish. This day I wept bitterly. Nerves and spirit utterly forsook me. Yet Thy will be done.

Stephens was released in October 1865. Afterwards, he was elected governor of Georgia in 1882 and died soon thereafter.

Fast-forward to 1957. In the age of planes and nuclear bombs forts lost their strategic importance. The US Government was getting rid of them, selling off the no-longer-needed real estate that it owned. In Boston’s case, islands.

Georges Island was sold at an auction to a company that wanted to use it to store nuclear waste.

Edward Rowe Snow (a Boston Harbor historian and enthusiast, about whom I wrote before) was appalled by this. Snow and his friends founded the Society for Preservation of Fort Warren. Snow was elected a president; he fought hard to ensure that Fort Warren’s ownership is transferred to the State of Massachusetts and the fort is preserved for the future generations.

Snow has won that battle. In 1961, the fort was open to the public; it’s been a nucleus around which the Boston Harbor Islands State park was established in 1971; and then it turned into the Boston Harbor Islands National Park Area in 1996.

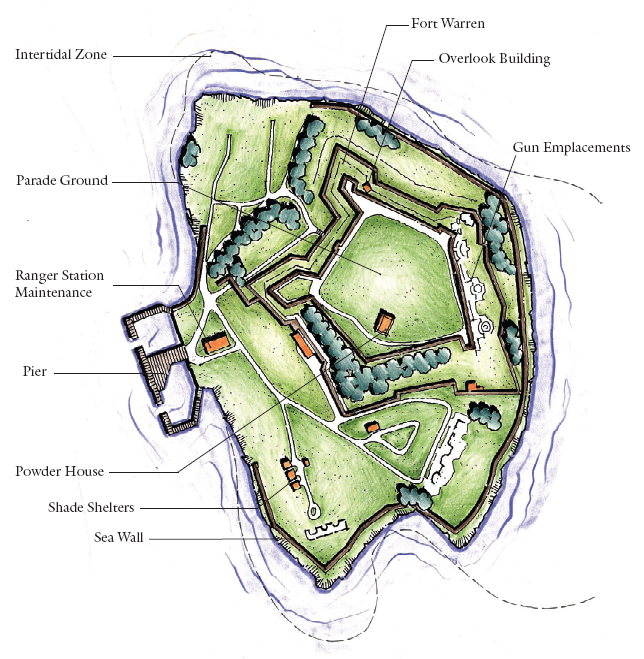

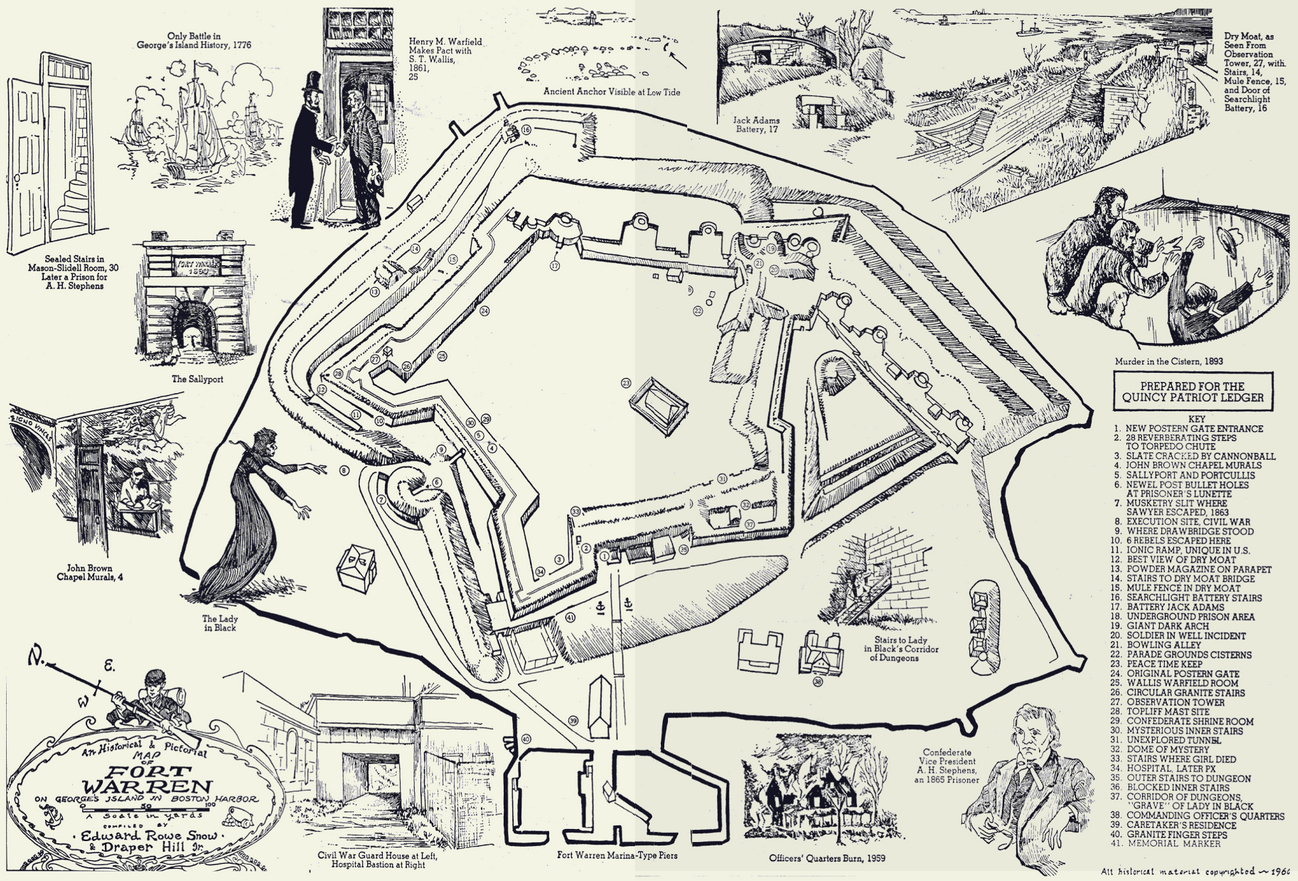

Here is a map of the fort prepared by Snow in 1960:

On the map you can see a ghostly silhouette labeled “The Lady in Black”. Here is her story.

Snow loved Boston Harbor and the islands, and genuinely wanted to impart his love and interest on other people, kids and adults. To make it more entertaining, he had to add stories about ghosts.

The inquiring reader should read Snow’s rendition of the story in his book, but in the nutshell it goes like this:

During the Civil War, a young Confederate lieutenant was imprisoned in Fort Warren’s dungeons. Somehow he managed to notify his young wife. She managed to travel all the way to Hull, and — again, somehow — sneaked into the fort, dressed as a man. They tried to escape by digging a tunnel, but where caught and brought to the fort commander Colonel Dimmick. The young lady attempted to fire at the colonel, but her revolver misfired, killing her husband instead.

The young lady was sentenced to hanging as a spy. Her last wish was to die in women’s clothes. There were no women on the island, but they finally found a black robe one of the soldiers used “for entertainment”, and in that robe she was hung.

“At various times through the years,” continues Snow, “the ghost of the Lady in Black has returned to haunt the men quartered at the fort.”

There is no evidence that any part of this story is true (and Snow never claimed that); I am convinced that he invented it himself. (There is a video on YouTube where Snow himself tells a simplified version of the story.)

Oftentimes Snow would bring tours to a dark chamber in fort and tell the story, and then his accomplice (sometimes his daughter) would make scary noises in the dark. Snow’s plan definitely worked out — the legend of the Lady in Black made the fort more interesting and memorable for the broad audience.

Even now, many years after Snow’s death, the rangers at the fort still tell the story. I’ve heard it myself, and saw a coworker trembling and claiming that she definitely saw a ghost in a pitch-dark room where we went to investigate.

We have spent too much time recounting the history of the fort and the island. Yes, we barely scratched the surface, but September days are short, and we have to head back soon. Let us look around before casting off.

Old gun positions overlooking the shipping channel in the outer harbor. The islands of Great Brewster and Little Brewster on the horizon.

Zooming in, Boston Light on the nearby Little Brewster Island — the one that island’s namesake John George petitioned the legislature to build.

Looking left, another harbor lighthouse, the Graves Light.

Great views from the top of the fort! Of course this strategic position is why the fort was built here in the first place. Here is a tanker coming from Quincy negotiating Hull Gut, which we discussed in the Peddocks Island report.

And the city, of course.

Inside the fort.

Some guns are still there, pointing at the harbor, just as 150 years ago.

Parade grounds.

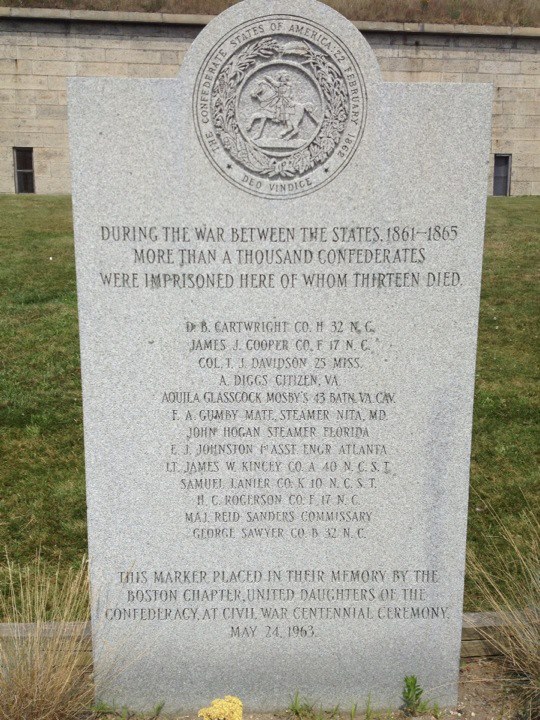

On the island, next to the fort, we stumbled upon this weird artifact, which I didn’t recall seeing before:

After further investigation, it turned out that this used to be a memorial marked to the Confederates who died while they were prisoners at Fort Warren. (Apparently, the only Confederate memorial in Massachusetts!)

Some more googling showed that it used to look like this:

(In parentheses, I found it quite remarkable that Boston Chapter of United Daughters of Confederacy was a thing!)

A couple of months ago our Governor (Republican, by the way) ordered to board the monument while its fate is being decided. It probably was not very controversial when it was erected. Edward Rowe Snow had the following lofty words to say about it in his book:

One of the most important services ever held at Fort Warren took place on Friday, May 24, 1963, when a massive stone slab honoring the Southern heroes who died while prisoners at this Northern bastille was dedicated. […] This fine memorial marker can be seen by any craft approaching the fort from the west and also by airplanes flying over or near George’s Island, where Fort Warren stands.

Well, the times have changed indeed! Apparently, the mainstream opinion these days finds even such innocent markers disturbing, and disturbs them as a revenge. The Boston Chapter of Daughters of Confederacy does not exist anymore. The Governor is mulling removing the marker from the island entirely. (We’ll keep an eye on it, and report back!) From a personal standpoint, I can only say that the country where I come from also had old monuments destroyed, and it didn’t really helped them much. For monuments really stand in peoples’ heads much more so than on streets, and they had better started with clearing the heads (but unfortunately nobody asked for my advice back then).

Speaking of Snow, though. Because of his efforts to preserve the island and the fort, his memorial also stands on the island. I’ve read about it before, and didn’t rest until I found it and took a picture.

Then, still at the same spot in front of the Snow memorial, I turned around and found myself standing quite close to the shore and looking at a beautiful view: islands, clouds, and the Sun sparkling in the ocean water. I am sure Snow would have approved this spot.

In every single book about Boston Harbor islands, I can clearly see the writer struggling how to begin and to end the chapters about an individual island.

I have no such problem. Every report about our island exploration starts with us arriving to the island on a sailboat, and it inevitably ends with us casting off and sailing home.

Georges Island was not different. After leaving the fort, we walked around, looked at the memorials, boarded or not, visited a gift shop where I bought a couple of books, and then it was the time to sail home.

We returned to our anchorage; our boat for the day, the Morning Gloria, was quietly waiting for our return. The wind hadn’t changed, still feebly blowing offshore. Good.

Our little rubber dinghy was also lying on the beach waiting for us. Landing on our islands from a keel boat is always a hassle — the docks are reserved for ferries, so we have to anchor offshore and deal with inflating and deflating the little dinghy — but it also provides a clear boundary between land exploration and water exploration. Sitting in the dinghy, as every strike of an oar leaves its fleeting marks on surface of the water, I was thinking back to Georges, that special island with gorgeous views and ghosts of the past which are still clearly there, no matter how much Governor Baker wants to mask their existence. I think my Father and Sergey have enjoyed the visit. Maybe it even opened some new horizons to them.

With that, we climb up the Morning Gloria, deflate and stow the dinghy, raise the anchor, and we are gone.

Subscribe via RSS