Salem Lighthouses

(Continued from here.)

Part 2. Derby and Pickering

As we were drinking rum and admiring the sunset, it got dark. Warm summer nights at anchor are no less romantic than sunsets. We kept drinking, and lights started turning on and flashing around us — buoys marking Salem Harbor channel, and the three neighboring lighthouses: red of Derby Wharf Light, white of Fort Pickering Light, and alternating white and red of Baker Island Light (which we’ve explored in Part 1).

Derby Wharf Light and its wharf are located essentially downtown. We’ve visited Salem quite a few times, and never needed this lighthouse for navigation: we always anchored and moored well before reaching it. But if you look carefully, you can see it from the anchor as well, across the harbor.

Next morning we decided to go ashore, to explore the lighthouse up close and personal, — and also to have breakfast. We inflated our dinghy, lowered it into the water, and rowed to Salem.

Mid-way, however, we got pulled over by a police boat. Literally pulled over, with flashing blue lights — well, at least he didn’t turn his siren on, and refrained from making shots across our bow.

The old policeman on the motorboat inquired where we were heading from and where to, and then started looking for something to pick on. He didn’t have to look for long: we didn’t have life vests onboard our little dinghy. “Well, what do you want now?” asked the old gentleman. “Given the circumstances, I just can’t allow you to continue your trip.”

He went on asking if we had papers for the sailboat and whether we had notified the Salem harbormaster that we were spending the night at anchor in “his jurisdiction”. We responded honestly that we hadn’t notified the harbormaster, and were not sure about the papers either since the boat was not ours (but rather belonged to the sailing club). “The plot thickens”, chuckled the law enforcement officer.

But ultimately he didn’t arrest us, didn’t fine us, and didn’t even make us stand in the corner. He just towed us back to our sailboat, backed off a little bit in his boat and conspicuously took a few photos.

At that point, we could put a few life vests in the dinghy and try again, but we got the message from the first try. We deflated and stowed the dinghy instead, had some breakfast onboard, and managed without an in-person exploration of Derby Light.

Meanwhile, it was time to head home. We raised the anchor under sail and started our unhurried way out of the harbor.

It is always satisfying to leave under sail. Unfortunately, that time our satisfaction was short-lived.

Right after leaving Salem Harbor, in a far corner of Salem Sound, the wind had suddenly died. No matter how much we tried to catch it — at least something! at least a whiff! — eventually we had to admit to ourselves that we were just drifting with the current. Which was not really safe (we could not steer the boat), but also not very practical (we wouldn’t be able to get anywhere at that speed).

On the other hand, we had more than enough time to view Fort Pickering Light, past which the current was carrying us.

So, as we are drifting out of the fine town of Salem, let’s talk about its lighthouses.

Last time we talked about what a challenging place for navigation is Salem Sound. Bakers Island Light was lit in 1998, but it alone was not enough.

Over 70 years have passed since then: the federal budget moves slowly. By the late nineteenth century Salem already stopped being a center of the international maritime trade; but there was still sizable local traffic in Salem Sound, and they still needed more navigation aids. In 1871–1872 there were three new lighthouses built here: Derby Wharf Light, Fort Pickering Light, and Hospital Point Light. All three are still standing, all three are still active. The last one, Hospital Point Light, is located in the city of Beverley, where I haven’t been yet. The first two are in Salem. Let’s talk about them.

The following map shows these lighthouses, and also Marblehead Light which we’ve explored before.

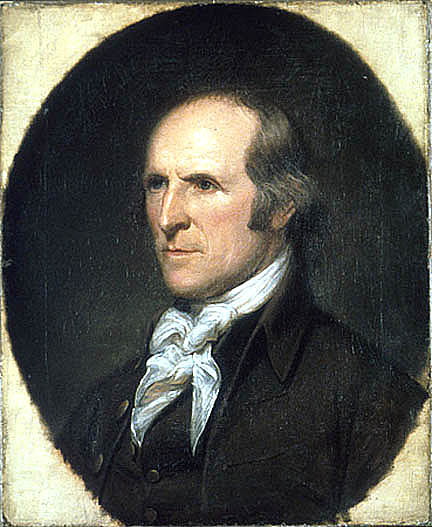

Derby Wharf, the longest wharf in Salem, was funded and built privately: by Richard Derby, Sr. (1712–1783), a captain and merchant from Salem. In 1762, when he started building the wharf, he owned at least thirteen ships involved in domestic and international trade, and his wealth only grew since then. I could not find his portrait, but here is his son, Elias Hasket Derby (1739–1799).

Elias not just inherited his father’s wharf. Though he never went out to sea himself, his ships were trading with India and China, coming back with silk, spices, and other exotic goods. This, we are told, made “King Derby” (as people called him) the first US millionaire.

In 1806 his heirs completed the wharf to its current length, and, when the time came to build a lighthouse, they sold the very end of the wharf to the federal government.

These days, there is a historic Custom House by the wharf.

And at the very end of the wharf there is Derby Wharf Light.

Derby Wharf was a busy place in its days. Today it is mostly empty, though there are still a couple of points of interest along the wharf. In particular, the tall ship Friendship of Salem is usually docked here. She is a fully operational replica of the merchant ship Friendship, built here, in Salem, in 1797. That Friendship was trading local goods (timber and dried cod fish) to exotic ones (pepper, spices, sugar, coffee, tea, silk), and while doing that, circumnavigated the globe for fifteen times.

When recently, in the covid April, I visited Salem by bike, the Friendship was beheaded, and stood without masts, spars and rigging. They were lying nearby: I hope they’ll put them back after maintenance. At least the beautiful figurehead lady at the bow was flying as proudly as before.

Derby Wharf Light at the end of the wharf is probably the smallest and the most unassuming out of our lighthouses.

It hasn’t changed much since it was built, just got repainted: it was red originally.

Derby Wharf Light is special: it never had a keeper’s house nearby. It was so centrally located in Salem that the keepers stayed in their normal houses, and just came to the lighthouse every day as to any regular job: completely unimaginable luxury in their profession!

In 1977 the Coast Guard had decided that they no longer needed Derby Wharf Light, and deactivated it. However, as it often happens in New England, the locals disagreed with this decision. In 1983 Friends of Salem Maritime, a local volunteer organization, repaired the lighthouse and lit it again, red light flashing every 6 seconds. Lights like this are marked as “priv” (private) on the navigational charts; like, the Coast Guard acknowledge their existence, but don’t bear any responsibility for them. That makes Derby Wharf Light different from Bakers Island Light: though the latter’s building was given to a non-profit organization, the light itself is still maintained by the Coast Guard, and thus it is an official light, with no priv.

Though I just called Derby Light “unassuming”, I already want to take it back. Each and every lighthouse is still a lighthouse; when you stand next to it, breathing the fresh sea air, when you see it as a part of the seascape where it belongs — it is beautiful nonetheless.

Onward to the next Salem lighthouse — the one past which we are drifting right now. It is Fort Pickering Light, also known as Winter Island Light. Winter Island itself is now connected to the mainland, so one can (and should) get there by a bike.

The light — and the island — are located at the point where Salem Sound becomes Salem Harbor. Given this strategic location, there was a fortress built there as early as 1643. Initially it was called Fort William (after King William), then Fort Anne (after Queen Anne). Following the American Revolution it was required to give the fort a more revolutionary name. It was renamed after Timothy Pickering, a Salem native who served as secretary of state under Presidents George Washington and John Adams.

Allegedly, the idea was that after passing past Bakers Island with its light, Salem-bound ships would continue until they are on one line with Derby and Pickering lights, and then follow that line into Salem Harbor channel. If that’s true, I at least hope that they were bearing slightly to the left from Fort Pickering Light.

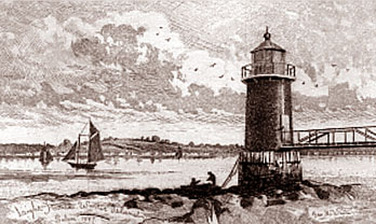

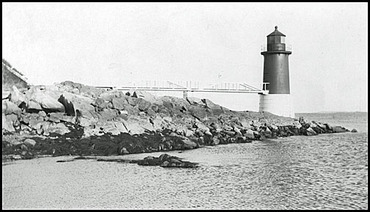

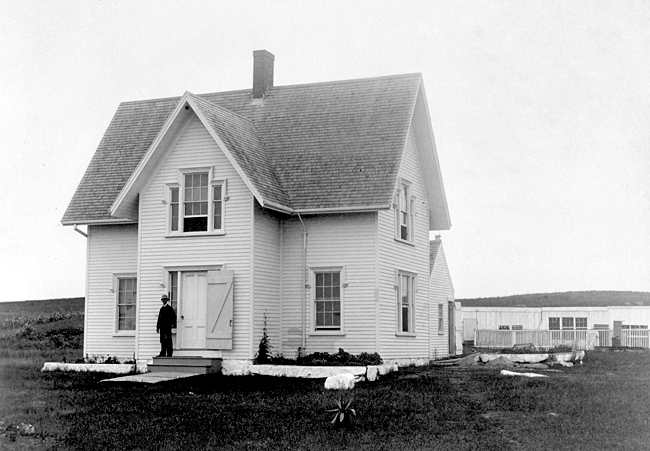

As to Fort Pickering Light, it hasn’t changed much since it was built — though, just like Derby Light, it changed its color from red to white. Also, it used to be connected to the island with a wooden bridge. The keeper lived in a house on the island and walked to the lighthouse over the bridge.

John Harris served as a Fort Pickering Light keeper for 37 years: 1881 to 1919. There were no shipwrecks on his watch, which is quite remarkable, but even more remarkable is this: when he retired at the age of 75, it turned out that he was absent from the lighthouse just for 5 days over all those 37 years. Before his retirement, Harris never saw Salem in the dark, and never rode a car (all the five times he visited the town, he was riding his horse). The day he retired, he went to see a movie the first time in his life. It just happened to be The Lighthouse by Robert Eggers.

After retirement, the Harrises moved to a busy Salem neighborhood. “I feel that I shall miss the quiet and freedom,” wrote John’s wife Annie. Life without quiet turned out impossible for them: Annie died in a few months after moving, and John followed her soon thereafter.

The Coast Guard had turned the lighthouse off in 1969 — having decided, presumably, that the red buoy 22 (on the photo above) was more than sufficient for navigation. And again, concerned citizens came together, founded a new organization (the Fort Pickering Light Association), raised enough money, repaired the lighthouse, and lit it again in 1983. It flashes white every four seconds, and is also marked as priv.

This is how it looks from Winter Island.

It is so handsome that a cyclist in a pink helmet can’t stop looking.

Meanwhile, it was not safe and not particularly constructive to keep drifting in a narrow busy channel. So we had to yield again, turn on the cursed diesel, and leave Salem Sound under power.

Out there, in the Atlantic, the sun was shining bright, and we finally caught some very reasonable breeze. The sails quivered, then filled tightly with air and acquired just the right shape; our hearts also filled tightly — with joy; the engine was killed right away, and we happily proceeded close-hauled into the open ocean.

In three miles away from shore all other sail boats were left far behind. We changed our tack and pointed south-west, towards Boston. Sergey got tired of steering, and we balanced the sails as well as we could and locked the steering wheel. And it worked! The boat kept going and maintained her heading on her own for two hours, until the wind shifted and we needed to change our heading.

Sergey had lovingly called the non-existing helmsman “the Ironman Sailor” and kept praising his performance. Drunk with his freedom from the wheel, he went to the bow and stayed there for a while, watching the ocean. And then I hear him yelling, “There she blows!” “A whale!”

The distant whale made a spout, dove back and disappeared.

And we — we had closed the Salem chapter of our journey and headed now towards the Graves Light.

Subscribe via RSS