Crab Alley at Peddocks

That day we were not supposed to be visiting Peddocks Island at all. Ben, Lena and I had a boat for two days of the July 4th weekend, and were planning an overnight cruise. The forecast for Friday was for north-east wind 10–15 knots, building up to 20 in the afternoon, with gusts up to 25 knots and 3–5 foot waves.

So we even agreed on the overnight destination: the south shore town of Scituate with a cozy, well-protected harbor. I originally thought of stopping for lunch in Cohasset, the town “before” (which is to say, to the north of) Scituate. However, the wind would have precluded us from anchoring in the outer Cohasset Harbor (or, rather, the waves would have precluded us from staying at anchor in peace), and there is no space to anchor in the “the Cove” (inner harbor). I called Cohasset harbormaster the day before, and she told me that all the moorings were taken either, so it took Cohasset out of the lunch spot consideration.

Instead, we ended up sailing in Boston Harbor, past Peddocks Island and into Hull Bay, where we dropped our anchor next to Spinnaker Island, just offshore from the town and the peninsula of Hull.

Spinnaker Island! I’ve never been close to it by sea before, though I did pass it by bike. Maybe I’ll write a separate post about it, maybe not; it’s a sad island. It used to be called Hog Island, and it was similar to all other islands in the harbor: some history, some greenery, a fort. And then, in the 1980s, it was sold to so called developers, who developed it into a gated “resort-style beach-front community”, destroying its fort and its history in the process and putting a literal gate with a guard on the causeway connecting the island with the mainland. And then, to add insult to the injury, they renamed it to Spinnaker Island — for no reason whatsoever, just because it sounded cool. Though what do I know, maybe they ran some focus groups or something.

Sad story — an island lost forever — maybe I won’t write about it anymore. I don’t like writing sad stories.

Anyway, there was a mooring field full of moored boats immediately to the east of Spinnaker, and we anchored outside of it. The Hull peninsula, as expected, protected us well from the ocean waves, but surprisingly not from the wind: bent by Hull hills, it arrived at the anchorage with vengeance, and loudly sung its shrill song in the rigging.

It was not particularly cozy in the cockpit; we had to go down below for lunch. Lena kept voicing her disappointment with this cold July day. To me, abrupt weather swings are an intrinsic part of living in Boston. We don’t complain about the weather, we embrace it.

With that, we raised the anchor, and then raised the sails, killed the engine right away, and under the reefed mainsail and jib quickly and effortlessly sailed through Hull Gut, a narrow and sometimes challenging strait between Peddocks Island and the tip of Hull on the mainland.

And right after we emerged from Hull’s protection, it started. We were now, though still in Boston Harbor, exposed to the Atlantic wind and waves. Ben, who was steering, soon asked for another reef in the mainsail: the boat was overpowered and hard to handle.

We sailed past Boston Light, to the end of the channel, left Boston Harbor and started to steer a compass course to the next waypoint, a green buoy in two miles.

The Osprey, our boat for the day, had some serious problems with her compass, so while Ben was sailing close-hauled, as close to the wind as he could, I kept double-checking our heading with my handheld compass. Soon I could see the buoy with my eyes — two miles is not that far — and, having convinced myself that we were not going to run over the rock behind the buoy, I could finally look around and try to assess what we were signing up for.

The gray water under the gray sky was covered with white caps and foam. The waves, much larger than 3 feet to my eyes, kept coming at us as gray walls, hitting the bow, and disappearing in spray and foam. The only other sailboat I could see was going in a parallel course to us, under a reefed mainsail only; I remember being impressed that the waves were higher than her sides, so with each wave cresting it looked like the other boat was sailing underwater. I am sure they thought the same of us.

Ben’s face is always hard to read, but Lena was sitting hugging her knees with that intense expression on her face that I interpreted as a survival look. She was not smiling.

“How long till Scituate?” she asked. — “About three hours.” — “Is it going to be like that all the way?” I made a mistake to respond, “At least like that”. She looked back at me in the way I didn’t like at all.

And then we reached the green buoy “1HL”, and started looking for Minot’s Light, our next waypoint. And… it was not there! I followed the coastline with my eyes, and here was the problem. To the right I could clearly see Hull with its beaches, and Boston Harbor islands beyond. To the left, the coast was disappearing into nothingness very fast.

Fog! The bane of my existence, the absolutely worst weather to sail. The situation started to look like a repeat of our ill-conceived trip to Provincetown in the end of May, when we ended up sailing for hours in thick fog, in strong wind and high waves, and then spending a night in a completely untenable anchorage with the very same fog, wind and waves.

Back then, it was clearly a lapse of judgment on my part. In fact, today’s destination of Scituate was partially my attempt to atone for the Provincetown transgressions: Scituate Harbor is very well protected.

But yes — we did turn back from the fog, the waves and the long-planned overnight trip and pointed the boat towards Boston Light. Thank you, Lena, for being there and helping me to turn back. That’s the skill I still didn’t fully acquire on my own. When the going gets tough, I tend to embrace pain and suffering and try to outlast them. Not sure that’s the right approach to life in general; but the ocean in particular often requires more flexibility. Teach me, and I’ll try to learn.

Turning back into the harbor, we were on a broad reach: the wind and the waves were mostly behind us. As the waves kept pushing the boat forward, there was even some fun in that! I took the wheel, and Ben tried to shoot a video of waves. It is hard to do: they look way more menacing, way more real in real life.

Once we reached the protection of Boston Harbor islands, the waves went away, and sailing back was almost effortless, though tinted with disappointment. The only exciting moment happened when we realized that in the thrill of our wave-fighting a long docking line off the bow got uncoiled and stuck in something at the bottom of the boat, probably in the prop.

This brought me some PTSD from the last time we fouled the propeller. We made a few unsuccessful attempts to moor under sail by Georges Island (to investigate the problem); on the last one I was steering, and when I looked around, I saw the island right ahead, terrifyingly close, with us barely having enough speed to avoid it.

Then Ben, who was not on that prop-fouling trip, and thus didn’t have any PTSD, proposed to just put the engine in reverse briefly. That worked like a charm, the line got dislodged right away, and we, still under doubly-reefed mainsail, continued our easy and melancholic sail home. We even docked at Spectacle Island on our way, and went on a brief walk.

Once back at the club, some of us stayed on the boat overnight — so we still can call this an overnight trip!

In any case, that was just my short explanation why we were supposed to be in Scituate the next day, and not exploring Peddocks Island. But Scituate was not meant for us; the next day turned out quite different — partly sunny with very light wind; my wife had joined us; and so we decided that some island exploration was in order. Peddocks Island is large and interesting, and has a nice cove or two, well protected from north and east; and that’s where we pointed the Osprey.

Peddocks is one of the largest islands in Boston Harbor (it has the longest shoreline of them, though Long Island is larger area-wise). I wrote a report about one of our previous visits to the island. There I recounted a fair amount of the island’s history.

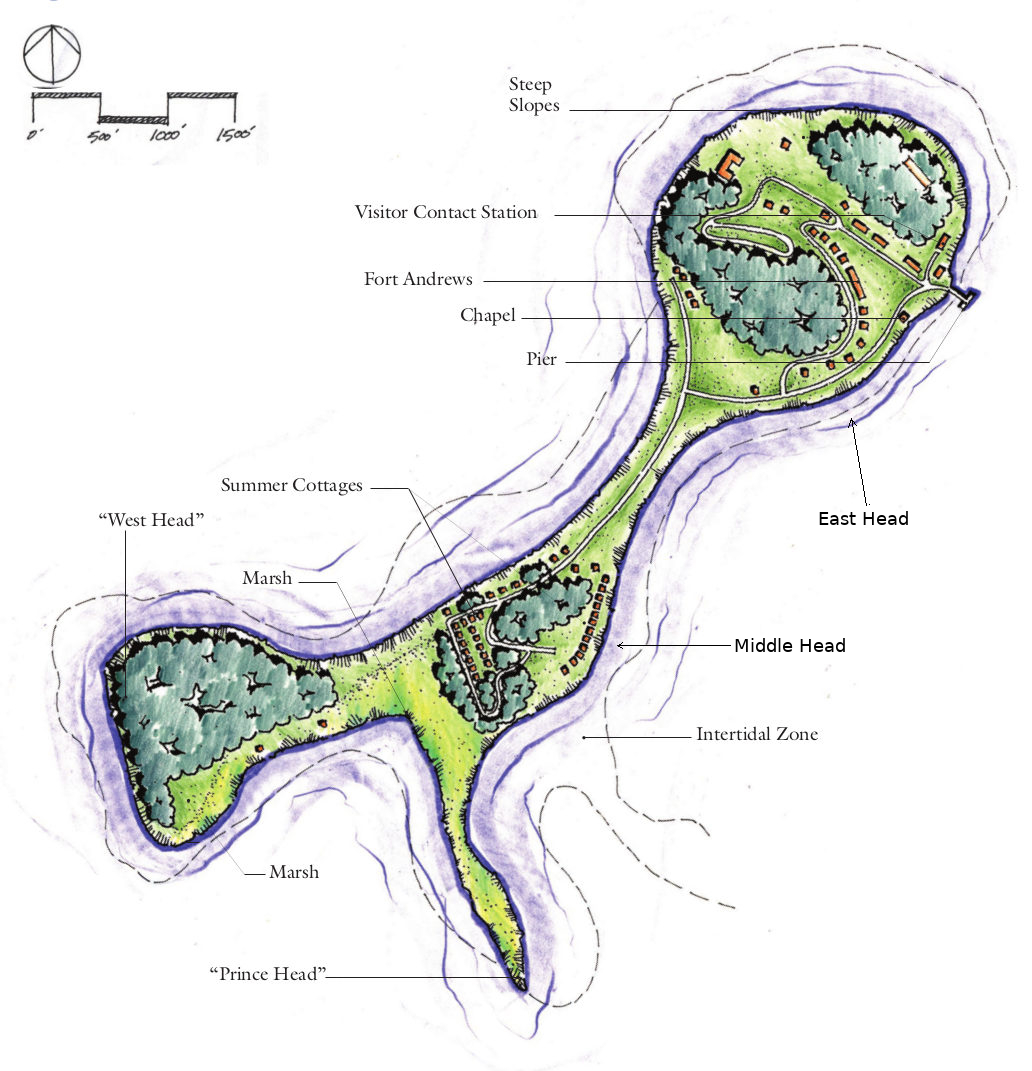

If you remember, the island consists of four or five hills of the glacial origin, called here “heads”:

Let’s see… East Head, Middle Head, West Head, Prince’s Head… and maybe some other head, depending on how you count.

Last time we anchored in Perry Cove and went left, to East Cove, to explore the fort there.

This time, Perry Cove was covered with mooring balls — apparently, installed last year together with Gallup and Georges islands mooring fields — and with boats, both tied to the balls and anchored outside of the fields. We decided that some revenge for yesterday’s failures was in order and confidently moored under sail, with Ben at the helm getting all the praise.

Then, as usual, there was swimming off the boat (cold, but tolerable), eating, drinking and much rejoicing.

And finally we inflated our dinghy and started rowing ashore. At that point we realized that the mooring ball that we grabbed was actually pretty far from shore. We kept rowing, and the distance was not shrinking nearly as fast as we would’ve expected. Next time let’s remember to moor closer to the shore, or even eschew the mooring, and anchor even closer.

Sooner or later, the paddles won over the wind and the current, we reached the beach, sparsely populated by a few motorboaters who brought their boats stern first and anchored directly into the beach. This time we decided to go right, towards Middle Head, and explore the cottage village there.

The cottage village originates with Portuguese fishermen.

Portuguese fishermen have long immigrated to Massachusetts — most of the original immigrants being not from mainland Portugal, but rather from the Azores, where New Bedford-based whalers started hiring them as early as in the 1700s. I know that there was a large and important community of Portuguese fishermen in Provincetown — as you come there by boat, you see a powerful art installation of photos of elderly Portuguese fishermen’s wives. “They Also Faced The Sea,” it’s called.

I don’t know much about Portuguese history in Boston, but it makes sense that the fishermen followed the fish and settled down in fishing ports.

Some time in the nineteenth century, a bunch of them squatted some land on Long Island and built themselves some shacks there. Back then, as throughout Boston history, the authorities didn’t care much about the islands, and the Portuguese could’ve stayed there for many years flying under the radar (if you allow me such an anachronistic expression). However, in 1887 one of the Long Island’s hospitals needed to expand, and that required more land. That’s when the government noticed the Portuguese settlers, and asked them to please get out of there.

They probably were simple, unsophisticated people. However, they needed somewhere to live, so they took their huts and floated them to another island — East Head of Peddocks. That would be an entirely non-trivial undertaking for these people. Lena, who is from Portugal, says that they exhibited the quality called desenrascanço, which is traditionally considered to be a fundamentally Portuguese trait — the ability “to hack or to improvise a solution to a problem”.

Unfortunately for them, in 1898, just in 11 years, the federal government acquired that part of the island to build a fort — the same fort we’ve explored before, and asked the Portuguese to please get out of there. So they uprooted their houses again, and floated them again — this time, to another part of the same island, Peddocks Island’s Middle Head.

The narrow isthmuses connecting the Peddocks heads are called tombolos. We landed on a beach side of one of these tomobolos, then found an unpaved road going parallel to the beach behind a thicket, and followed the road as it climbed up Middle Head.

Going up, the road was beautiful, surrounded by trees from both sides and from above, like a green tunnel. From time to time we could see cottages on the sides, most of them in different states of disrepair, but no people.

The story behind the crumbling cottages, the way I understand it, goes like this.

When the state government took the entire island by imminent domain in 1970, they wanted to evict all the cottagers who, remember, never owned any land on the island. By that time people were living — mostly summering — in those cottages for generations, and were understandably upset by this turn of events. But the situation was awkward: the island was made into a state park, a part of the Boston Harbor Islands Park Area; people are not supposed to live in a park.

Eventually — in 1992 — they came to a compromise with the government: people currently living in the cottages were allowed to stay (and to pay a land use fee to the government), but they were forbidden from selling them or passing them on to their heirs. When they die, aDCR (Department of Conservation and Recreation, the state agency managing the island) takes possession. And what do they do with this newly acquired property? They nail the doors and the windows shut, and then and just allow the cottage to disintegrate. No wonder that the locals are not overly enthusiastic about the government.

In any case, that’s my understanding of the origin of the crumbling cottages. It is hard to believe that somebody will abandon this great place out of their own will.

The road has finally reached the top of the hill, to an opening where there were many more cottages, most of them cute, cozy and well taken care of.

Their dwellers were out too, enjoying a warm and sunny Independence Day. By the edge of the hill there was a gazebo, and from that hill there opened some very, very nice views to the cove, and the islands, and the Boston skyline behind Long Island and its invisible bridge.

The locals like to use lighthouse motifs in landscaping and architecture.

This area of the island used to be called Crab Valley. It’s not hard to figure out what those fishermen were salling here.

Lena noticed that nobody around us talked in Portuguese or displayed Portuguese flags — only American. She attributed it to the Independence Day: “We need to come back on a Portuguese holiday!” I am afraid though that some of them were long-assimilated Portuguese, and many were not Portuguese at all.

Christopher Klein in Discovering the Boston Harbor Islands quotes one Claire Hale, who has spent over 70 summers in her cottage on Peddocks:

My family has been coming here since 1917. My uncle did business with the Portuguese fishermen. When my uncle told them his son had rickets, they told him to come to Peddocks Island and put him out in the sun for the summer. So he rented a cottage and stayed all summer. And when he took the boy back to the doctor in the fall, his legs had straightened out. So my uncle bought a cottage.

When my father came to this country from Italy he was eleven years old. Peddocks Island was the first place his older brother took him. And when my father met my mother, he took her here and she fell in love. My father came here until he was seventy-five years old. At one point our family had ten cottages on Peddocks. We turned the island from Portuguese to half-Italian!

So not only she boasts of her family on their own destroying the Portuguese domination on the island — more importantly she claims that living on Peddocks cures diseases. I can definitely believe that!

Meanwhile, the road (street? trail?) took a left there, and we followed it. Only later, studying the map, I realized that, if we were to go straight, we would’ve reached West Head. Oh well, after so many visits, there are still unexplored parts, still a powerful incentive to come back.

There were more cottages there. Some women were working on an art project: placing colorful flip-flops, all different, on a large board. Unfortunately, we didn’t take any pictures.

Overall, everyone we’ve seen was at ease. There was this feeling of a large party in the air; since the land is all public and a part of the park, we didn’t feel bad of walking essentially through other people’s backyards. Lena noticed that nobody was wearing masks; as if we were in some island paradise untouched by the virus.

The cottages suddenly were over, the road became again a green tunnel, and we found ourselves on a beach on the other — south-eastern — side of the island. There, a much more classical tombolo of sand and gravel led to Prince’s Head, a steep hill that looked way too steep to climb, surrounded by more sand, gravel and rocks. When we were sailing past it the day before, on a high tide, it was hard to believe that it was a part of Peddocks Island; the neck of the tombolo was hardly visible from the water.

In the 1870s the federal government was testing some huge cannons, firing them from Nut Island across the channel into thick steel plates placed on the bluffs of Prince’s Head. I biked to Nut Island back in May; obviously, there were no traces of these artillery experiments remaining there, and likewise nothing remains of them in Prince’s Head today… at least I think so.

The narrow strait between Nut Island and Peddocks Island is called West Gut. We spent some quality time sitting on a rock and looking at boats traversing West Gut.

…And then, as it always happens, it was time to go back. We retraced our steps to the little village, a special place, the only remaining example of people living on an island the way they used to do it for centuries, rather than in a sterile soulless suburban development of Spinnaker Island.

There is no electricity in the village, no running water. People are improvising — installing solar panels, collecting rainwater.

It was hard not to see that this special place was coming to an end, that DCR would keep devouring it till the end. For that matter, the entire island, quiet and remote, might also be on the verge of a change: there are new “development” plans for it as well, involving building, among other things, “a luxury hotel, a spa and a waterfront café”.

All good things in life come to an end, and people are particularly good at developing destroying quiet and remote places.

Our project in life is to visit them — explore them — experience them while they are still beautiful and reasonably unspoiled. Sadness about the future mixes in our hearts with happiness about the present. The present is always much, much stronger.

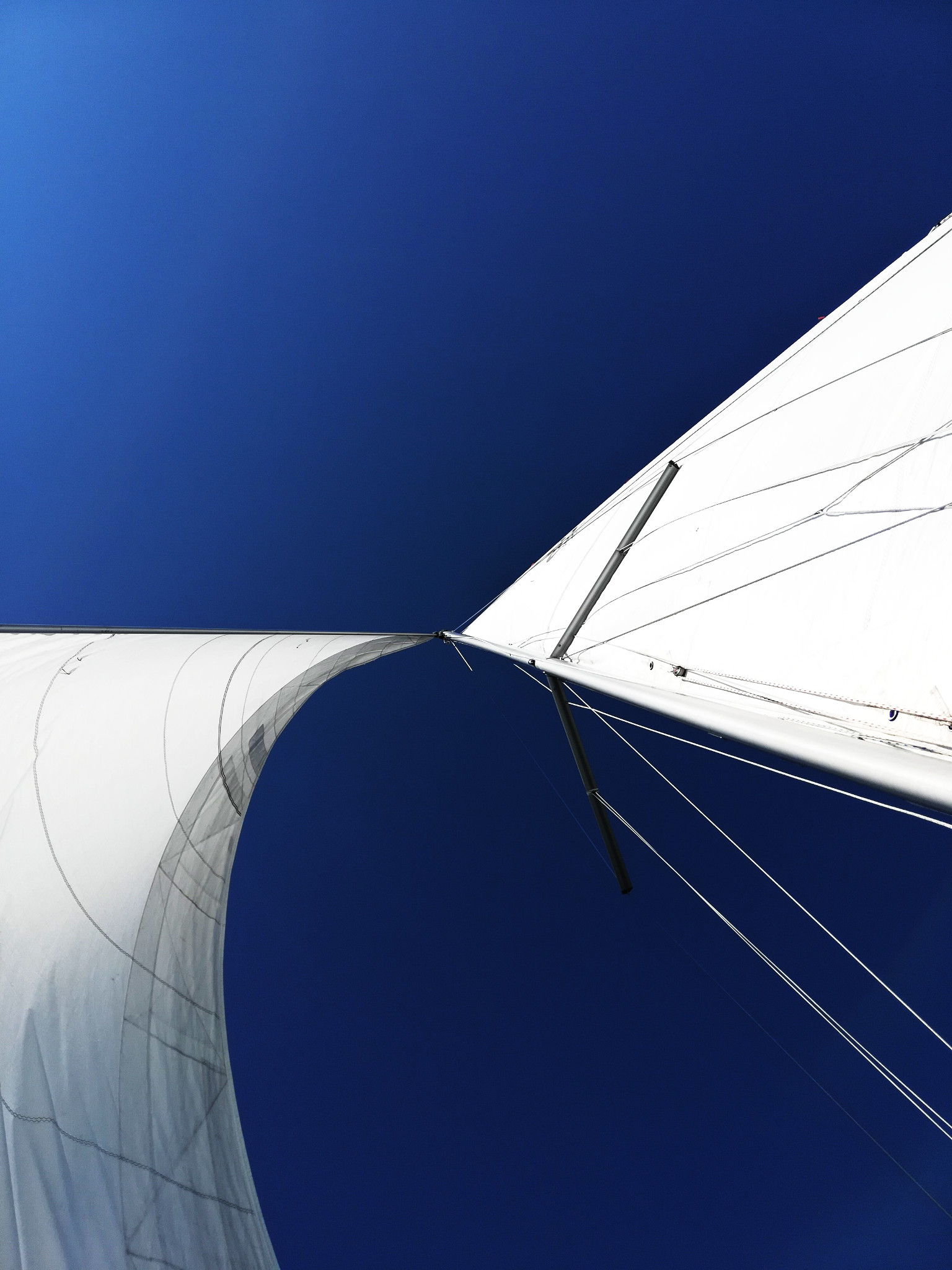

With that, we row back to the Osprey, catch the wind, now fresh and lively, and point the bow towards the city. On a broad reach, with the wind again mostly behind us, the sailing is easy. Yesterday’s disappointment is long gone.

That was an Independence Day well spent. The sails and the wind — they are our independence.

(*) Photo by Lena.

My Peddocks Island photos are from a previous trip (June 2018).

Subscribe via RSS