Beyond the Cape

The Beginnings

When I am going to be a skipper on a sailing cruise, before each cruise I get overexcited, but with a bout of panic mixed in. What if the boat is no good? What if the weather is terrible? What if we get lost and run aground?

And every single time, everything goes great and everyone has the best time of their lives.

In particular, our trip to Spanish Virgin Islands back in January was a huge success; I thought that not only I but also my crew as well enjoyed it a lot and wanted more.

So back then I decided to get a club membership for the upcoming season that included a week-long cruise in Buzzards Bay and the vicinity. Then, of course, the coronavirus struck, and the future of the human race of sailing suddenly became less clear, so for months I could not even get properly excited about the upcoming trip.

But then the virus had suddenly retreated; the sailing season had finally started, though late, and soon found its groove; and by early July it finally hit me: the Buzzards Bay cruise was happening; it was imminent.

Now, let’s set the stage for the trip.

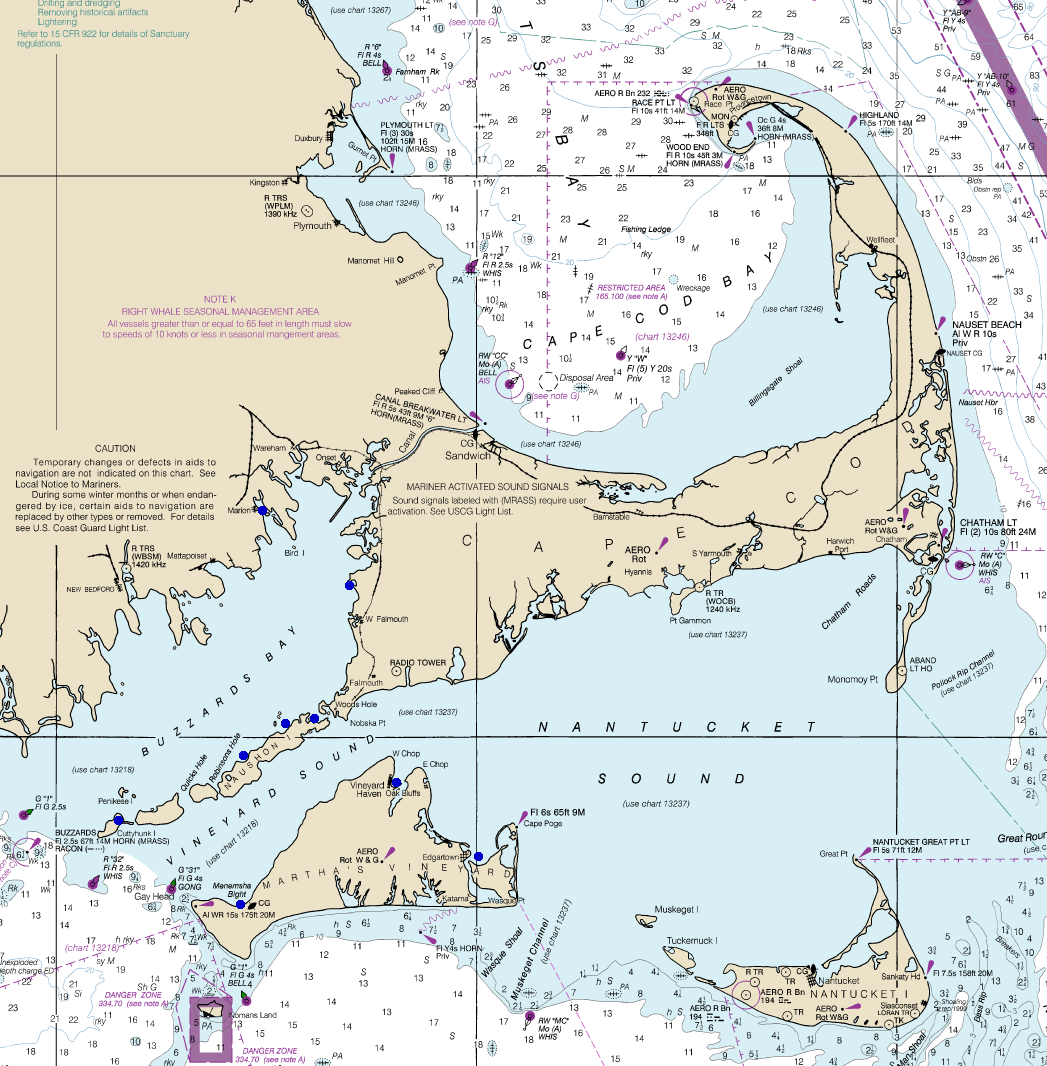

There is this set phrase in Massachusetts, “the Cape and the islands”. The Cape is, of course, Cape Cod, and the islands are where we were going to be cruising. I keep saying “Buzzards Bay” as a shorthand, but our trip was in fact happening in three bodies of water: Buzzards Bay that separates the mainland (to the northwest) from Cape Cod and from the Elizabeth Islands, a chain of wild, mostly private islands; Vineyard Sound, separating the Elizabeth Islands from the island of Martha’s Vineyard; and finally Nantucket Sound, the largest and the most open of them, separating the south shore of Cape Cod (to the north) from the islands of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket.

Buzzards Bay, by the way, was named after a large bird of prey which the early explorers thought was a buzzard. It was in fact an osprey (there are no buzzards in Buzzards Bay). Since then, the osprey numbers had declined significantly — in Buzzards Bay and elsewhere — because of the DDT poisoning and other reasons, but they were rebounding lately.

This chart (clickable, as all images) shows “the Cape and the islands” and our cruising grounds: Buzzards Bay, Vineyard Sound and Nantucket Sound. Our stops are marked with blue dots.

These “cruising grounds” were supposed to be one of the best on the US East Coast, if not in the entire country.

What makes cruising grounds good? Stable winds (and good weather in general), good stops in an easy half-day sailing distance from each other, and a good variety of them too. And just beautiful surroundings.

So then, after months of planning, excitement, and panic attacks (much more planning and excitement than panic attacks, thankfully), we — Ben, Lena, Sergey and I — showed up in the town of Marion where Anne, our boat, was waiting for us at a mooring in Sippican Harbor.

That was the first time we met her. The Anne, a Beneteau 343 made in 2007, looked a little tired but in a good overall shape and ready for an adventure. We surveyed her, put our stuff in, and got ready for the departure. Then finally somebody went on the bow and cast us off the mooring ball — and at last something had properly switched in my head, and I went from the planning and worrying mode to the “let’s ride this adventure” mode.

And ride we did! The forecast we had for that day was for very light wind, and we were concerned about not being able to get anywhere. Instead, as it often happens with weather forecasts in our parts, it was wrong. We did get some very reasonable breeze, and the boat was easily doing six knots.

This first wind of a long sailing trip is always special; it does indeed blow all the worries away, and sets the mood for the entire cruise. It was clear that we would encounter many different conditions over the course of the week, but starting with a good wind — and sunny, warm weather too — felt like a very good omen.

The omen, indeed, came true. The cruising grounds turned out all they were claimed to be. Beautiful waters, beautiful shores — in particular the wild Elizabeth Islands, but really everywhere else, too — relatively short passages, warm weather and warm water perfect for swimming…

I planned this trip for a nice diversity of lunch and overnight stops, to experience the most of what that area had to offer. That worked out very nicely. We mostly anchored, but we also moored a couple of times, and once spent a night docked at a marina. We stayed in wild, remote coves with just two other boats anchored alongside; in sleepy villages (but popular boating destinations) of Cuttyhunk and Menemsha; and in touristy resort towns in Martha’s Vineyard.

Almost all our stops were either in the Elizabeth Islands or in Martha’s Vineyard. I tried to steer away from Cape Cod and the mainland; there are some nice destinations there as well, but they just felt less “special” than the islands. And then (because of an unfortunate accident, which I will retell in due time) we never managed to get to Nantucket, leaving it for the next time.

Remote Anchorages

The Elizabeths are almost all private, owned by different clans of the Forbes family, a prominent Boston family who made their fortune on the opium trade with China. They kept the islands undeveloped, except for an occasional mansion here and there, and in their natural state, and also generously allowed the public to use a few small islands and a few beaches. Hence our complicated view of the Forbeses: on the one hand, it’s not cool to privately own these beautiful islands and to keep them (mostly) to yourselves; on the other hand, they do act as stewards of the land, and sailing by these islands and enjoying their unspoiled beauty, it is easy to imagine yourself sailing these same waters two or three hundred years ago. I am not sure there are other places in Massachusetts like that.

Our very first overnight stop was in Kettle Cove in Naushon Island, one of these Forbeses’ islands. That was one of my favorite anchorages, and the most similar to our Virgin Islands experience: just an empty beach, no trace of human presence, and two or three other boats anchored in the cove. You don’t find places like this in Boston!

Actually, though Kettle Cove was on my “nice-to-visit” list, that day I planned to advance further, probably even to Cuttyhunk — the furthest of the Elizabeth Islands, and the only major one which is not private. But as we were happily sailing along, we saw some pretty thick fog creeping up exactly from where we were heading. I looked around, saw some masts where Kettle Cove was supposed to be, pointed the boat and that direction, and called it a day.

Fog! I try to stay away from it if I can, especially from the thick, dense, can’t-see-your-own-hands kind of fog that envelops you, exhausts you, and sucks your soul dry. I find sailing in this kind of fog not satisfying, — just stressful and dangerous. And yet this year it keeps coming to me, starting with our very first sail of the season, to Provincetown, when the fog caught us offshore unawares.

This time, it was different: the fog was not hiding at all, and we had a chance to avoid it. But it had caught me by surprise back then, and it kept coming back no and then through the entire trip.

Thanks to the fog, though, we got to spend a night at Kettle Cove.

There was a somewhat funny incident when we were just dropping the anchor there. The cove was not well protected, and as we were looking for the best possible spot to spend the night, we inevitably ended up close to other boats who had made the same decision before us. Not dangerously close — just close. There was an older couple on the boat closest to us, and as we were setting our anchor, the woman from the other boat cried out loud, “Why here?! You have the entire harbor!”

I immediately admitted that she was right. I remember reading somewhere that anchored boats exhibit herd behavior, and felt a little bit ashamed of doing the same. Especially in these wild coves, people come there to stay away from other people, and we all should certainly respect that. So we moved back, slightly away from them, and then another boat came, with a man and a dog, and they dropped their anchor precisely where we were for the first time! The woman protested loudly again, but unlike us, the man and the dog didn’t care.

We went ashore, where the public was allowed to access the beach but no further, walked around and enjoyed the sight of the peacefully anchored boats against the fog-accented sunset. Beautiful sunsets are an important part of every sailing journey. Most of the boats had left by that time, and we spent the night with just two or three other boats.

I liked this wild anchorage so much that I made an effort to get something similar again, and finally succeeded by bringing the boat to Hadley Harbor. It was originally intended to be a lunch stop — the only way I could fit it into our itinerary — but when we reached it for a late lunch past 2pm, my crew said, “What if we just stay here for the day?”, and it made me quietly happy.

As a poetic gesture of fate, Kettle Cove was our first overnight, and Hadley Harbor was the last — and also the only two overnight stops in Buzzards Bay, by the Elizabeth Islands — so the trip ended up very nicely framed.

Hadley Harbor is a very well protected parcel of water surrounded by three large Elizabeth Islands (Uncatena, Naushon, and Nonamesset) and a few small ones. This gives it a very different feel from Kettle Cove. If the latter is just a strip of a beach, Hadley Harbor is a maze of (mostly narrow and shallow) waterways surrounded by unspoiled lush green nature. No sandy beaches, but rather herons, egrets and ospreys instead. The shores are mostly private and forbidden, but it doesn’t stop one from enjoying them.

Sleepy Villages

I guess I am hardly hiding my bias towards anchoring at wild, uncivilized, not crowded (if not empty) anchorages versus any other kinds of stops. But I did enjoy the other kinds too.

Cuttyhunk (the only major public island out of the Elizabeths) and Menemsha (in Martha’s Vineyard) were two remote sleepy villages I’d wish we had time to enjoy more and without haste. Wikipedia lists the Cuttyhunk population as 52 people (though mentioning in the very same article “10 year-round residents”). Menemsha is slightly larger, but still very small (it was made famous by the movie “Jaws” which was shot there). Both places, though sparsely populated on land, are popular and busy boating destinations. It is said that mooring and docking fees comprise one quarter of Cuttyhunk’s budget.

Cuttyhunk is the more remote of the two; it occupies an entire island. Formally speaking, Cuttyhunk is the island; the town is called Gosnold, after Bartholomew Gosnold (157–1607), who is considered to be the first European explorer of Cape Cod and the Elizabeth Islands.

There are just a couple of streets in Cuttyhunk. Nobody uses cars; people — even the police! — drive golf carts or just walk around. The only grocery store in town was supposed to be open till 2pm, and when we came over at one o’clock, it was already closed. They live on the “island time” here — the notion usually associated with some tropical destinations like the Caribbean. It was somewhat inconvenient, but at the same time I was happy to find it so close to home. The only ice cream shop in town was open, though; I guess that’s what really counts.

The BSC cruising guide describes Cuttyhunk and Menemsha very aptly; I couldn’t say better:

“Visiting Cuttyhunk presents the classic paradox of travel to all remote and uncommercial places: how to appreciate them without undermining the very qualities you came to admire. [It] is a working island town whose residents, both year-round and summer, have chosen to live just outside the patterns of mainland life.

It’s a choice that’s familiar to any sailor who has spent hours beating upwind or drifting in calm rather than turn on the engine.”

“With just one street of small shops, surrounded by beach, dunes, grass, mixed forest and vast saltwater ponds, Menemsha feels seductively like the edge of the world. Residents and visitors alike come here for the unhurried, untucked mood it engenders.”

In Menemsha, we decided to hide in the “basin” — a very well protected inner harbor — from the wind, the waves, the fog and some imaginary problems with our dinghy. There was no room to anchor and no moorings available inside, and we ended up docking. That actually was probably the most stressful part of our trip. The “slip” in Menemsha consisted of four wooden pilings, and was not really designed for a poorly-maneuverable sailboat, especially in a strong crosswind. Of course, we did get a strong crosswind, our boat got blown onto pilings and at an angle to the slip. Our motorboat neighbors, Sam and Peggy, helped us pull the boat in; I don’t know how we would have managed without them. Undocking the next morning was equally challenging — arguably harder — and again Sam and Peggy saved our day.

Beyond the docking/undocking adventure, though, living at the dock was interesting. On the one hand, crowded, loud, no chance to go swimming off the boat the way we got used to. On the other hand, the ease of access: you just step off the boat, and you are “in town”. Unfortunately, the showers were closed because of the covid, but everything else was open. Not to mention the electrical connection at the dock (which we didn’t use), the water hose (which we did use to fill our water tank and to wash the boat), and when I called the harbormaster about pumping out the holding tank for our head (toilet), to my surprise a young man just appeared at the dock with a long hose, saving us the trouble of motoring and docking somewhere else.

Later at night, when all the loud parties around us died away, and the marina was asleep, I was just standing on the deck and appreciating the night. The stars were bright, and added to them were marine lights and sounds: a bell and green and red flashes of the channel buoy and markers; steady anchor lights of the boats anchored outside in Vineyard Sound; the remote but bright flashing light of Gay Head Lighthouse. That’s always a very potent feeling for me, like being in a parallel universe… But then of course I was also surrounded by street lamps in the marina, so a certain suspension of disbelief was necessary.

So in the end, as often in life, it was a special experience with its pros and cons. I wished we had more time to explore Menemsha and Cuttyhunk, but that was in conflict with our desire of making sailing progress. One week is not nearly enough time! Give me a month, and then I’ll stop feeling bad about finding some great places only to leave them in the morning, and instead will explore them leisurely, the way they deserve.

As to Menemsha, we needed to leave it early to ride a favorable current in Vineyard Sound. My plan called for leaving no later than nine o’clock in the morning, but we woke up to more fog again, and the crew was not in the mood to hurry up anyway. So we had breakfast, bought some freshly caught fish from a fishermen shack right on the dock, and went through the pumping-in-water and pumping-out-waste activities I already mentioned. By eleven o’clock — our absolutely latest departure time if we wanted to sail down Vineyard Haven, as dictated by the currents — we were done with the chores, and the fog had completely evaporated, as if never existed. Sam and Peggy helped us to push our boat by hand as far out of the slip as we could, so then I could put the engine in gear and face the wind before being blown hard at a piling. (We all miscalculated at the very end, and did touch a piling after all — softly, and with no obvious damage to the boat. “They told me that the pilings are our friends,” said Sam. “I am not sure I believe that.”)

Touristy Towns

So that was Cuttyhunk and Menemsha, and it was perhaps not a coincidence that they came one after another. Then we left that relaxed and sleepy corner of the world, and sailed to the population and tourism centers of Martha’s Vineyard: Vineyard Haven and Edgartown. We would’ve stopped in Oak Bluffs as well if we weren’t delayed in Vineyard Haven by the most unfortunate accident, which I will retell in due time.

I had been to both places by land. A few times to Vineyard Haven: it’s a more industrial one, with a ferry terminal for big, car-carrying ferries from Woods Hole. Edgartown (I had been there once by bike with my dad, and on that trip we’d biked through Menemsha as well) is richer, more upscale. I always find it exciting to visit familiar places by sail for the first time, and they invariably open from a different side, making the experience richer.

These were busy places, with shops, supermarkets, restaurants — and a lot of people, mostly in face masks. In Vineyard Haven, we even sat in a restaurant for dinner (outdoors). For me, it was the first restaurant meal since March, when everything around me got shut down for the coronavirus. I realized that I completely forgot the feeling of other people feeding me and serving me. It was weird and vaguely exciting.

In Edgartown, we were going to rent bikes and explore the island of Chappaquiddick, including its lighthouse, Cape Poge Light, which I haven’t seen before — at least not close. However, the fog, our old nemesis, made its reappearance. The entire town suddenly got enveloped in thick fog; we decided that biking in the fog, though probably less dangerous than sailing, was no fun either, and returned back to our boat.

(As a side note, Chappaquiddick is a weird island right to the east of Martha’s Vineyard proper: that in some years it is an island and in some years it isn’t, depending on the state of a sandbar on the south shore of Martha’s Vineyard. Sometimes, it gets breached, and sometimes, the water and the wind push the sand back and connect Chappaquiddick to the main island again.)

The Anne was anchored in the outer harbor, maybe two-thirds of a mile away. As we got there by the dinghy, the bright sun was shining over the boat: the fog turned out to be contained to the land.

Instead of biking to Cape Poge Light, we raised the anchor, and sailed there to enjoy the afternoon and to take some lighthouse pictures. The moment we came back and reclaimed our anchorage, the fog finally advanced past Edgartown and into the outer harbor. As we grilled the fresh bluefish we had bought earlier in Edgartown, ate our dinner, and settled down for the night, the fog kept thickening more and more. Finally, we could barely see even the boats anchored next to us, only the vague outlines, with their anchor lights, unfocused and blurred in the mist. It was simultaneously an eerie and romantic feeling; I don’t think you can quite get that on land.

On the other hand, our first night in Vineyard Haven was clear and crisp. I went swimming in the dark, and to my surprise found the water to be bioluminescent: with each stroke, little bright points of light would light up all around me. It was not as intense as my experience in the Spanish Virgin Islands, but it was still magical, and I take magic any time it is offered to me.

Then I climbed up to the deck, and found Sergey, our ship’s CAO (Chief Astronomy Officer), scanning the sky with binoculars. Turned out that he was looking for Neowise, the comet of the year. And he found it below the Big Dipper! With a naked eye, she looked just like an unremarkable star, but in the binoculars she had a long, very well-visible tail. Then we took the binoculars off, and there she was, now clearly and unmistakably visible with her tail. That was a great night both for underwater and celestial observations.

The next morning showed us a beautiful, perfect sunrise over the distant Cape Cod coast.

Lena, in her trip report, mentions how important it is for her to share the moments like this with friends. I would go further, and say that the entire trip was such a moment — critically important to share with friends. Thank you to my crew for being there and sharing with me this glorious sunrise, both literal and metaphorical.

And now is the time to tell you about the sad accident that kept us in Vineyard Haven that day.

The Blockage

In the morning, right after breakfast and before casting off to the next adventure, we learned that our head (marine toilet) was clogged. A clogged toilet, especially when it’s the only one around, is bad news in any circumstances, but it’s particularly devastating on a sailboat which can lean over or be hit by waves when underway. This can cause the contents of the bowl to spill over and make a sad situation even sadder.

And so, on that warm and sunny summer day, we were marooned at an anchorage with a non-functioning toilet, and unable to go anywhere.

Fortunately, we already had it happen to us before — on the previous cruise, aboard the Pura Vida in the Spanish Virgin Islands. Back then, it took ten minutes for Ben to save the day with a clothes hanger. So we chuckled a little bit, and I gave Ben a hanger that I brought from home for this very purpose (well, and to hang my clothes too, but cleaning the head pipes was clearly more mission-critical).

Imagine our disappointment when Ben emerged with bad news: the hanger didn’t work. By that time it was clear to me that we were not going anywhere. I started to call the boatyards and marinas in the vicinity, and also the sailing club, but nobody could or wanted to help us. Ben was working on the head for hours; then we did a trip ashore to a local hardware store and bought everything plumbing-related that we could, including a drain snake. The snake, the only snake in the store, was quite useful, but unfortunately not quite as long as we needed.

Turns out (I had no idea before) that if the sea water stays in the pipes and reacts with a certain liquid substance, calcium deposits — small and not so small pebbles — grow as a result. We ended up extracting a whole lot of them from that head pipe by the end of the day, so no matter what the immediate cause of that clog was, the entire system had been a disaster waiting to happen.

By the evening, with Sergey joining Ben in the head, we were almost but not quite done, and then we had a bright idea to motor to a nearby town dock where there was a hose with fresh water. Originally, we were just going to refill our water tank, but then it occurred to us that water under pressure can be very effective in unclogging clogged pipes. And that’s exactly how it turned out! In half an hour, we had a fully fixed and functioning head, a full fresh water tank, and a washed-over, clean deck and cockpit.

We spent that night on a mooring in the inner Vineyard Haven harbor, behind the breakwater and close to the ferry terminal — just in case. We rewarded ourselves with grilled fish and copious amounts of rum, and then nature rewarded us more with a clear quiet night and another glorious sunrise the next morning.

Being moored in the middle of the action, next to the ferry terminal, with these huge ferries running from 6am to midnight, was an interesting experience on its own — a marine equivalent of being in a busy city and watching all the activity: ferries, working boats, yachts, launches, dinghies.

Not bad at all; I enjoyed it and it was a nice change of pace; but my heart longed for more quiet and solitude, and this is why we ended up in Hadley Harbor.

Woods Hole Transit

To get to Hadley Harbor, though, we first needed to go through Woods Hole — one of the most complicated channels on the East Coast. Buzzards Bay and Vineyard Sound are separated by a long chain of Elizabeth Islands, with narrow channels — “holes” — between them. Unless sailing around Cuttyhunk, in Rhode Island Sound, one has to take one of these holes to go from Buzzards Bay to Vineyard Sound and back. Some of them are too narrow, too shallow, too twisted and too ill-marked and not recommended for cruising sailboats. That leaves us with two usable holes — Quicks Hole far out, and Woods Hole next to Cape Cod, the town of Falmouth, and its same-named village of Woods Hole. Since the tides are quite different in the two bodies of water, there are some pretty strong currents in the holes most of the time, and that’s what makes them interesting.

In the beginning of our cruise, when we sailed from Cuttyhunk to Menemsha, we went through Quicks Hole. The channel there was pretty straight, and the opposing current that we faced just slowed us down and gave us more time to appreciate the beautiful shores.

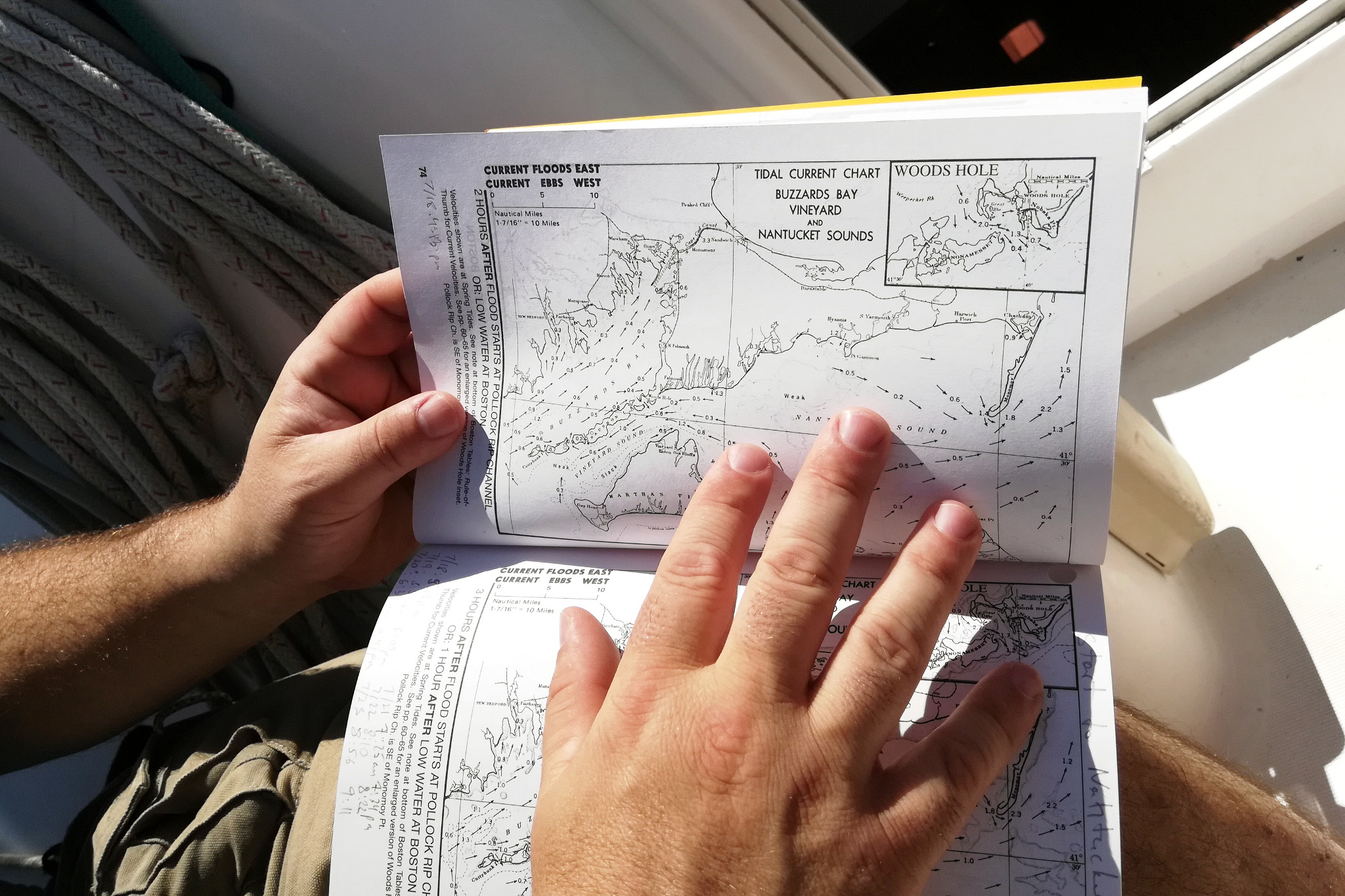

Woods Hole is quite different. It consists of two or three very narrow channels intersecting at an angle, with rocks on both sides. The current can run up to 4 knots according to the current table, and in practice can reach up to 7 knots. For a sailboat doing 5–6 knots on a good day (both under sail and under power) that alone could be an insurmountable problem. But the worst problem is that, because of the channel configuration, the current sometimes runs sideways (“cross-current”), and instead of just speeding you up or slowing you down, as it would in a straight channel, it pushes you at the rocks.

The Woods Hole channel itself is tiny, maybe a mile across if at all, but there are pages upon pages written about how to negotiate it. Some charter companies even forbid their customers to transit Woods Hole. I remember the first time Lena and I were discussing it, she was also like, “Let’s not go there!”, which of course only strengthened my resolve to actually do it.

Consequently, I spent a lot of time planning the transit and trying to time it reasonably well. Most of the time the current runs uncomfortably strong in either direction. The plan was to hit at the tail-end of the opposing current, so it slows us down a little bit, making things happen at a more deliberate pace. And if we were late, we would hit the slack current, which would also be good. With that approach, you can imagine that the channel has a door that is open for two hours every twelve hours, and closed at other times: you shall not pass.

The morning we left Edgartown for Woods Hole, though, I grossly miscalculated the amount of time it will take there. It was a combination of the wind (more west than the expected southwest) and a strong head current, stronger than I expected, that significantly slowed our progress. As we were crossing Nantucket Sound from Martha’s Vineyard to Cape Cod, Falmouth and Woods Hole, close-hauled, heeled steeply and only doing three knots over ground, I kept checking the time, got eventually resigned to the fact that we would be late for the Woods Hole transit, and started making alternative plans.

But we made it in the end. After a few tacks in the vicinity of Nobska Point Light, where the current was weaker, and we could thus make better progress, we positioned ourselves at the entrance of a short channel towards Woods Hole. I checked the time — it was past 2pm — we were running more than an hour and a half late compared to my original goal. It meant that we had missed the weak current against us; missed the slack current too; and now the current had already started in the same direction that we were heading, getting stronger and stronger, but reasonable so far. It was time to make a decision. I said “go!”, and we entered the Woods Hole channel.

As I said before, it is a small place, and also very well marked with buoys. That can create its own problem, though, as it is easy to confuse buoys from different channels and lose your way. I was steering, and as Lena and Sergey were tracking the buoys in the channel and accounting for them in the chart, I just kept looking back from time to time to verify that we were not getting set (pushed sideways) by the current. That was not the case, and in fifteen minutes we easily emerged on the other end.

I thought it was somewhat anticlimactic, compared to the amount of time we planned for it and stressed about it, but just the way it is supposed to be. Navigationally, it was definitely a highlight of that day and the entire trip.

The Conclusion

And so, how did the entire trip go? I put together a plan — a potential itinerary — before the trip, fully aware that the chances of actually following it were almost non-existent. The wind, the weather, the mood of the crew, the technical condition of the boat — there are just so many unpredictable variables. And indeed, there was no way to predict the plumbing fiasco.

That said, we followed my potential itinerary pretty closely, with the only major exception of skipping Nantucket. Oh, Nantucket… it was so hard to let you go. Next time we’ll head straight for you, I promise.

So: we sailed through most of Buzzards Bay. We followed the entire chain of the Elizabeth Islands, from Hadley Harbor to Cuttyhunk Island. We sailed through the entire Vineyard Sound. We followed the habitable shores of Martha’s Vineyard, from Menemsha to Vineyard Haven to Edgartown. We transited Quicks Hole and Woods Hole. We observed and photographed six lighthouses. (Lighthouses are dear to me… I’ll write about them separately.)

Until the very end all our stops were on the islands from “the Cape and the islands”, but it just so happened that on the very last day we hit the Cape. We were looking for a lunch stop with an unusual for these parts north/northeast wind (the prevailing winds are all southwest). I found a promising-looking harbor, Wild Harbor in Falmouth. The cruising guide didn’t have any good words to say about it: “Wild Harbor … offers nothing for the cruising boater … not recommended for anchoring by anyone but the locals…”. Still, we went there; as expected, it was very well protected from the northeast. We dropped the anchor smack in the middle of the harbor, ate our last lunch, swam our last swim, and then sailed a direct course to Sippican Harbor to return the Anne — having finally visited Cape Cod. I must admit, Wild Harbor was fine, though pretty tame and not wild at all — but definitely less interesting than our island stops.

Were these cruising grounds all they were claimed to be?

In my opinion, absolutely! The sailing was great. The stops were close enough so we could plan easier challenging or relaxed days. Most days somehow turned out relaxed, but that’s not a bad thing. The scenery was beautiful, the stops diverse and all great, and the water warm and inviting — we kept jumping in at any opportunity. The only thing that, though good, could be better was the weather. It was supposed to be settled weather with consistent southwest wind 10–15 knots. That’s how summers roll there. Instead, we got pretty unsettled weather, a day with no wind, a day with northeast wind, — all that made it harder to plan ahead as we were going. And fog, a lot of fog, completely unexpected on my part.

Granted, we had a very similar situation in the Virgin Islands past January, where the famously consistent trade winds turned out not so consistent at all. So, in both cases, we just fell back on our Bostonian habit of not being surprised by any weather, or by how fast it changes, and enjoying it regardless. “Embrace the weather,” as Lena likes to say now.

We practiced resource management a lot, in particular fresh water and the holding tank. My crew performed with flying colors: we never ran out of either. I learned to talk to harbormasters and pump-out boat operators. Finally, without our traditional chef Koby, we all had to pitch in for food shopping and cooking and I thought that went quite well, too. Special thanks to Sergey for being our grill master.

The Anne only had two cabins. In general, she was large enough for four people, but the sleeping arrangements unsurprisingly turned out to be tight. I am very grateful to Sergey and Lena for sleeping in the salon — the couches there were too small for me.

I like sleeping outside on a warm dry night, and I brought with me a hammock (for the first time in my sailing career). Unfortunately, the first hammock try ended in a complete failure: it kept swinging violently in the fresh breeze and the waves, so I was sea-sick in the first ten seconds, and quite scared of falling off in the next ten seconds. I had to abort the hammock trial then and sleep down below, and after that I never could find a good night to try again — it was always either wind, or waves, or rain in the forecast. Well, one more project that will have to wait for the next time; one more reason to have next time.

There is one important thought, which I touched a little bit when talking about watching sunrises with friends. Now, in the Conclusion, is a perfect time to expand on it more.

It goes like this: socially speaking, sailing — and cruising in particular — is a somewhat schizophrenic activity. On the one hand, you are out at sea in your boat, staying so far away from other people that sometimes it feels infinitely far. Inevitably, sailors are self-selected people who are fine with being far away from the others — who typically enjoy it, in fact.

But on the other hand, people in the boat — the crew — are extremely close to each other. Even large boats are very small when you live onboard. There is a boat-handling aspect of it, where you have to trust your crewmates to do the right thing and not to put the boat in danger. But to me, more important is the life aspect of it — so I can trust my crew in general, and that they are good friends with whom I can share the many joys of cruising. This is exactly what this crew was, and exactly what this cruise was. Thank you, friends! You made our trip a success.

The cruising lifestyle is so different from my usual life, it always takes a few days to get used to it. As all the anxiety and all the worries went away at that first cast-off, that first sail hoisting, I let myself go with the flow, let the current and the wind, the sea and the air take me wherever it pleases them.

Then it happens to you in reverse. The last wind, the last tying to mooring ball, the last launch ride to the land — and suddenly you are marooned on land again. But after a great cruise — and this one was a great cruise, for sure — there is a strong after-taste in your mouth that can go on for months.

Eventually it runs out, and it means that the time has come for a new cruise.

Itinerary

Day 1. Sippican Harbor, Marion — Weepecket Islands (anchored) — Kettle Cove, Naushon Island (anchored)

Day 2. Kettle Cove — Cuttyhunk (moored) — Menemsha, Martha’s Vineyard (docked)

Day 3. Menemsha — Vineyard Haven, Martha’s Vineyard (anchored)

Day 4. Vineyard Haven (moored)

Day 5. Vineyard Haven — Edgartown, Martha’s Vineyard (anchored)

Day 6. Edgartown — Hadley Harbor, Uncatena / Naushon / Nonamesset Islands (anchored)

Day 7. Hadley Harbor — Wild Harbor, Falmouth (anchored) — Sippican Harbor, Marion (moored)

Here is a short video with a few clips from our trip.

Subscribe via RSS