Pure Life Magic

These days, we don’t sail cruising sailboats off the dock: it’s just too crowded, not enough room to maneuver.

Instead we delay the magic, turn the engine on and slowly motor out of the marina.

As the boat has cleared the breakwater and faces the open sea, the helmsman throttles down even more and points her into the wind. The crew starts hoisting the mainsail. The sail unfolds and starts flailing in the wind — already free, but still without purpose.

Then, when the sail is ready, the helmsman takes the the boat forty five degrees off wind and shuts the engine off. The sail, now full with the wind, acquires a shape and a purpose. The boat heels steeply and jumps forward.

This is it. This is when the magic happens, elevating our lives from mundane to extraordinary. The adventure begins. Life, just like the sail, acquires finally a shape and a purpose. I don’t even need to squint hard to see pixie dust sparkles flying off the surface of the sail.

In our case this is not a one-time spell either; raising the sail is our magic gateway to Fairy Country. The gates are opening, and they are letting us in.

The water surrounding us is not real anymore; it is of such intense, impossible shade of turquoise that it hurts the eyes.

Distant islands, themselves unreal, made of fog, beckon us. The waves are singing their enchanted song.

We are only an hour into the trip, but the air is already so thick with magic that I can easily see its effect on my crew. Their faces are shining with care-free smiles, all the wrinkles gone now. I feel ten years younger, almost weightless, carried away by the boat, flying forward.

The magic keeps going, intensifying. We see an arch of a rainbow rising straight out of the horizon. Enchanted, empty coves open their arms to us.

It culminates when one night, safely at anchor, alone in yet another cove, I jump into the water. The night is clear, and the heavens are full of impossibly bright stars. The water is luminescent here. I make a stroke, and hundreds of tiny, very bright sparkles float away from me in all directions.

With every stroke, I look down and see the sparkles in the black water. Then I look up and see the stars shining oh so brightly in the black sky. There is nothing separating them; in my eyes they merge together into one wonderful Caribbean constellation. The anchor light at the mast-top is just one bright star among many.

The water is warm and soft; the magic is strong; the night is young; my body is floating completely weightless. I can swim forever.

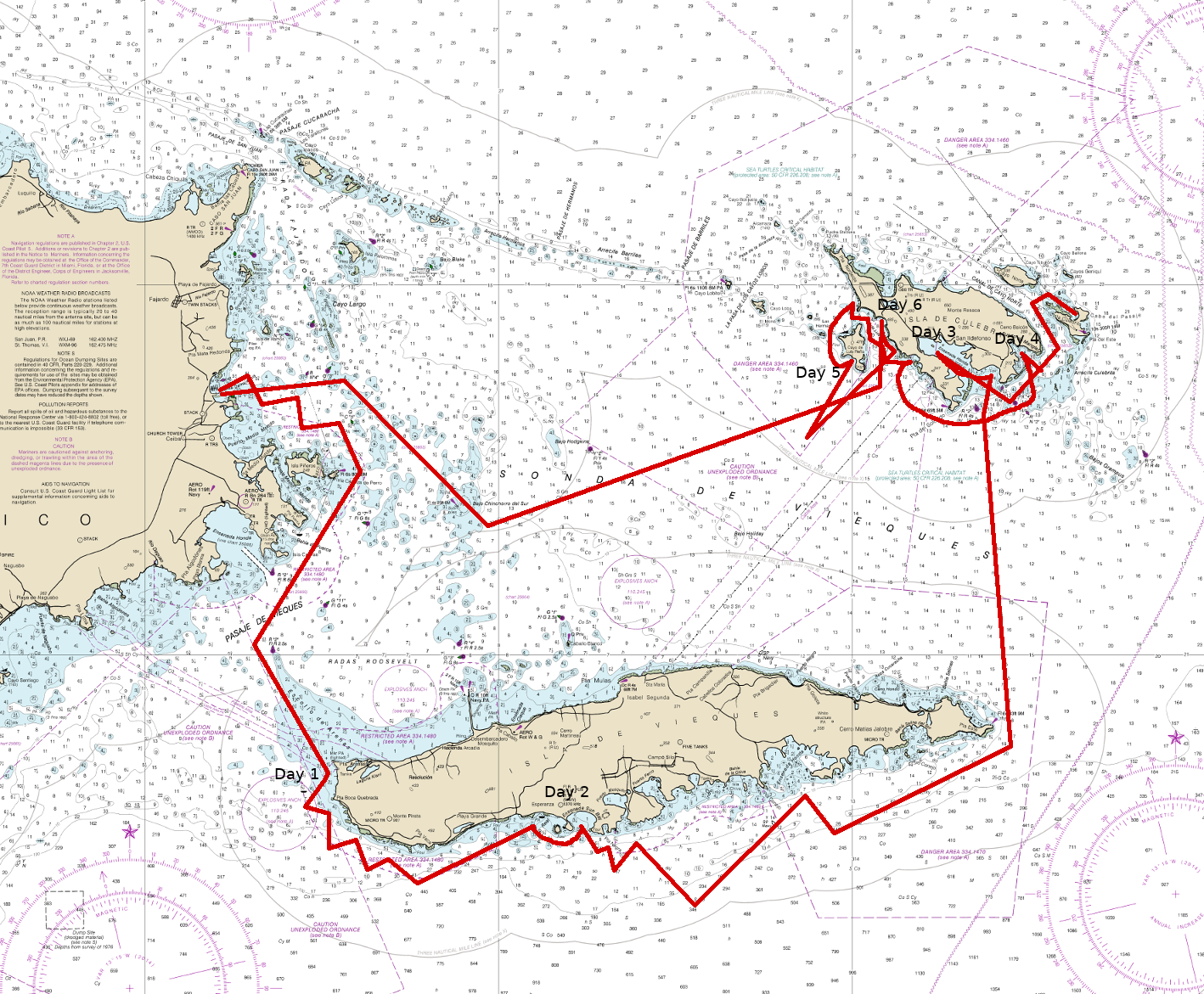

The initial magic of raising the sails and listening to the shrouds singing in the wind, it’s always there. This time we are going for a longer spell, though. We are in the East Puerto Rican city of Fajardo, embarking on a week-long sailing trip to the Spanish Virgin Islands, traditionally called the Passage Islands — a group of Caribbean islands sitting between Puerto Rico on one side, and the US and British Virgin Islands on the other.

Our boat is named Pura Vida. Literally “pure life” in Spanish, pura vida is a Costa Rican expression meaning “to live a peaceful, simple, uncluttered life with a deep appreciation for nature, family and friends; a ‘real living’ that reflects happiness, well-being, and satisfaction”. When I learned that a few months before the trip, I was struck by how close it was to my own concept of slow life, for which I was striving for many years — which this very blog was about. The boat name was a good omen!

Unfortunately, the boat herself is anything but pura vida — luxurious and filled to the brim with electric and electronic gadgets. The crew doesn’t complain about the luxury though, and we still have our magical slow life regardless. And still, I think the boat name is a good omen.

The weather, though delightfully warm, is more intense than I expected, with frequent showers, strong winds (good!) and high waves (not so good). It’s our first morning after spending the night aboard in the marina. I look at the forecast, and I have a feeling that we are not going anywhere today:

And indeed, José from the charter company refuses to let us out and we instead rent a car and go explore El Yunque, the only tropical rainforest in the United States.

The rainforest is great, the jungle, the waterfalls and all that (and the rain, too), but I feel an irritation inside. Why does it have to stand between me and the sea, between me and the magic?

The next day the waves subside though, the sailing ban is lifted and I get what I have been waiting for: six magical days in the Spanish Virgins, out of Fajardo to the islands of Vieques, Culebra and Culebrita, the pura vida, life the way it is supposed to be.

I’ve sailed in the Caribbean and elsewhere before, but this is the first time when I am a skipper on a long cruise in the waters and the lands which I’ve never seen in my life. That makes the adventure even sweeter: not knowing how a distant island, now just a misty outline on the horizon as if made out of dreams, will look in a few hours when we finally reach it; the anticipation of what is waiting for us around the next corner.

It always takes a few days, maybe two or three, for the stress of land life, the unhealthy eagerness to hurry, do things, follow plans, form opinions, — for all that go away, evaporate, leave the soul open to the slow and wonderful flow of the cruising life. Days lacking careful planning and specific purpose, but full in different ways: sea passages under sail; crystal-clear waters; anchorages in remote coves with deserted sandy beaches, palm trees, high cliffs; glorious sunrises and sunsets surrounding you from all directions; the impossibly bright starry night sky, the way you once knew existed, but has long since forgotten.

On clear nights we just lie in the cockpit on our backs and look up, into the sky punctured from time to time by shooting stars. Up west, Venus the Evening Star shines so brightly that it leaves a trail of light on the surface of the water. The world is quiet, except for the constant murmur of the waves, and we are alone.

The British Virgin Islands are known as the world’s cruising capital (or is it the charter capital?), with thousands of boats sailing their beautiful waters. The Spanish Virgin Islands, though geologically and geographically a part of the same archipelago, are different — delightfully empty. This is the high season, and yet we spend our nights anchored either alone or well away from just one or two boats sharing the cove with us. On our passages, if we see one boat in an hour, any boat, the sea feels crowded.

In Vieques, there are two famous bioluminescent bays, one of them the best in the world or some such. We can’t enter it in our boat, but we can sign up for a guided kayak tour for big dollars. We almost do it but suddenly have to change our plans and sail to Culebra, the next island, looking for an overnight anchorage well protected from the south. The unsettled weather with the wind uncharacteristically changing all over the place from day to day keeps giving us puzzles. It is not supposed to be this way, we are in the trade wind country after all, but after many years in Boston we know how to deal with changing weather. The challenge just adds to the fun.

The night before, as we don’t know yet that we will be leaving Vieques behind, is when I jump off the stern into the black water (a special experience on its own, we don’t swim at night enough in our lives) and encounter the strongest magic. We are not even in a world-famous bioluminescent bay, we are just spending a night in this cove, but the shining plankton is in the water here as well, floating away as I swim around, blending with the heavenly stars, and I have this elated feeling that the days of adjustment are over. I have finally arrived in Fairy Country.

Our days flow unhurriedly and worry-free. We sail, we swim, we snorkel, we fish, we eat decadent meals prepared by our glorious cook and drink decadent cocktails. Somehow this life makes much more sense to us than the one we left at home.

Sometimes we go hiking on the islands. One day some of us insist that we must visit Flamenco Beach, ranked the third best beach in the world by some people ranking the world’s beaches. The beach is wide open to the mean northern swell that has been building up for weeks, so we can’t anchor there safely. But we stay for the night in the thirty-minute hiking distance away from Flamenco Beach, and we decide to give it a try. A narrow but well trodden path, flanked by beautiful flowers, climbs over the hill, leads down and abruptly ends in a parking lot. It’s full of cars, people, loud music, food smells. My crew is taken aback; we haven’t seen any of that for what feels like a very, very long time.

When we come back to the beach where the Pura Vida is anchored, there is not a single boat, not a single person around. Flamenco Beach is long, and pretty, and not bad at all — but our beach, not ranked worldwide by the ranking people because it is ours and not theirs, is infinitely better. The entire crew, even the most die-hard fans of Flamenco Beach, unanimously agree that they would rather be here than there.

I go swimming at night again, and the water is full of sparkles again. In the light shining out of the boat’s cabin I see a school of blue fish sleeping, suspended mid-water.

The very last morning comes. We need to be back to Fajardo, 20 natical miles away, by ten in the morning. This means rising early and casting off in the dark.

Night sailing is magical in its own right. At home, one always sees blinking lights of navigation buoys and lighthouses, clamps of lights and sky glow of cities and towns. Here, in the Caribbean, the waters are dark, and the land is dark too. We switch off all the lights and electronic screens aboard, so the eyes can adjust to the darkness. I stand behind the wheel for the last time and steer the boat south in a channel between two islands, the black water surrounded by even blacker hills on both sides. We pass the island to the right; I wait a few more minutes to make sure we are clear, make a wide turn and point the Pura Vida westward.

In twenty minutes, the sky behind us starts lighting up: the dawn is over Culebra. In half an hour more, the sunrise is shining bright through the clouds. We leave it behind and steer away from the magic country into the world of highways and airports, houses and jobs, the world that feels much less real than the wonders around us.

We are all silent.

The impossibly-bright turquoise water, split by the Pura Vida’s bow, streams back and emerges as a white turbulent wake behind the stern.

Subscribe via RSS