Weekend at the Outer Islands

(This trip took place in October 2017. Continued from here.)

Day 2. Middle Brewster Island

I woke up in the morning and climbed up onto the deck through the hatch again. On the deck, I looked around — and immediately rushed back to get my camera.

When you spend the night anchored, the first thing you do in the morning is, of course, check where your boat is. Is she still where you left her last night? has she dragged her anchor? has she run aground or hit rocks?

But no, the boat sat happily where we anchored her has night, just pointed in a different direction (which means that the wind had shifted overnight).

And then, after checking all that, I raised my eyes and found myself surrounded by a sunrise of indescribable beauty.

The sun had already risen above the horizon, but it still was in that beautiful state when the day is young and tender and it feels like nothing is impossible. The sky was blazing with colors. The islands to the east of us (Middle and Outer Brewsters) were just dark silhouettes against the sky; the islands to the west (Calf Island, and the entire harbor behind it) were filled with that same delicate light brimming with endless vital force. How beautiful is Boston Harbor at sunrise! I could easily see the two lighthouses that shone for as at night — Boston Light and Graves Light — and also the two container ships, still anchored behind the Graves.

And once again, just as before, at night, that beautiful mixture of the infinite natural beauty spilled from horizon to horizon, and of the acute feeling of blissful solitude — there was no one around, all of that was mine, mine alone — this intoxicating cocktail got absorbed into my bloodstream and went into my head.

And then, in ten short minutes, the magic of the sunrise went away. The wild beauty of colors vanished, blended into the blue sky and blue ocean. The sun turned into an ordinary yellow sun. And that special, entrancing happiness turned into an ordinary feeling of deep satisfaction.

After that, it was essential to continue our explorations. The dinghy had remained inflated since the day before; we cast off the Cheap Sunglasses and set out towards Middle Brewster.

Middle Brewster belongs to the “Brewsters”, the outer islands that lie between Boston Harbor and the open ocean and protect Boston from the elements. There are four Brewsters per se. We visited two of them before: Great Brewster and Outer Brewster. The last one, Little Brewster, belongs to the federal government (Boston Light is located there), and the access is limited. We really need to try to sneak there. Maybe next season?

Calf Island, that we visited yesterday, belongs to the Brewsters both geographically, and by its character; it was previously called North Brewster for a good reason.

To recall, the “Brewster” here is William Brewster (about 1566–1644), an elder and spiritual leader of the pilgrims arrived on the Mayflower. (For more about him, turn to the post on Great Brewster.)

Here is a good view of Middle Brewster from Outer Brewster (October 2016):

In August, Sergey and I stayed here anchored, and the island was covered with crying birds (seagulls and cormorants) in a pretty aggressive disposition. Back then we had no desire to try and find common ground with them.

The official stance of the National Park Service on the subject of Middle Brewster is, access is discouraged. Especially during the nesting season. I never really knew the word “nesting” before. Probably because I am not a bird.

Anyhow, there were no birds on the islands over that weekend. Presumably, by that time the nesting was already over. In any case, the NPS warnings would have never stopped us.

Admittedly, others had warned us, too. Christopher Klein (in his book “Discovering the Boston Harbor Islands” which I had purchased recently) literally stated the following: “Middle Brewster is an untamed ocean wilderness, and even for the most experienced adventurer, exploring this island can be dangerous.”

Obviously, that didn’t stop us at all — but rather excited even more.

At first, the island looked completely impregnable. I would even say, splendid in its impregnability.

Max pointed out a landing spot which was even worse that the one on Calf Island the day before — not even a beach, just rocks in the water, slippery and overgrown with seaweed (and even more slippery because of that). We barely managed to carry our dinghy over them. Later we learned that Max did very well by finding this spot on the western end of the island: we, the experienced adventurers, ended up walking around the island, and couldn’t find a better landing place.

View from the water. Thank you Max for finding this beachhead (even though without a beach).

View from above.

I must confirm the “untamed wilderness” description. Out of all islands which we had explored, Middle Brewster was not just the only one with no proper beachhead, but also the only one with no trails and no traces of recent human presence. Go search for photos from Middle Brewster on Facebook and Instagram — you will hardly find any. Nobody manages to get there. Well, we did, and now we have pictures to prove it.

On any Boston Harbor island (even those which are connected to the mainland now) one gets a wonderful feeling of detachment from the city, detachment from the modern times. Like in a sci-fi movie, you cross the island boundary and get teleported to a different world.

This feeling is obviously stronger on real islands, unreachable by land. It is even stronger on the outer islands, on these Brewsters. On Middle Brewster, this feeling gets amplified to the limit.

When we talked about Calf Island, I pointed out its main, visible-from-afar landmark — the chimney stack. Middle Brewster has a similar landmark — a giant arch. You can see it on the island photo above (the one taken from Outer Brewster).

The history of Middle Brewster is somewhat similar to the Calf Island’s history, and features some of the same characters. In 1871 Middle Brewster was purchased by a man with an ornate name: Augustus Russ (1827–1892), a founder of Boston Yacht Club, and one of the leading Bostonian lawyers at the time. Naturally, he had built a luxurious villa there. He spent there his summers and commuted to Boston by his yacht. His friends called him “the king of Middle Brewster”.

That time was Gilded Age — the period in American history specifically known (besides many other things) by the provokingly luxurious mansions of the nouveau riche.

Unlike Cheney Jr and Julia Arthur, our friends from Calf Island, Russ absolutely didn’t insist on having the island all to himself. On the contrary: he subdivided the island to multiple plots and rented them out to other millionaires. Cheney and Arthur happened to be one of his tenants. In 1890 they built on the island a relatively modest mansion and called it The Capstan: every respectable mansion should have a name.

And this is how their idyllic life was over: Cheney had decided to build himself a standalone ice house, a structure for storing ice. There was no electricity and no refrigerators back then, but it was as important as it is now to drink your champagne cooled. Russ denied him: he had a rule that every tenant could build no more than one house.

This was the kind of insult Cheney couldn’t stand. He purchased Calf Island nearby, and started building there to his heart’s content.

Middle Brewster, as you could see on the photos, is surrounded by a pretty vertical rocky base. Above, there are some open rocky spaces and some thick thickets. As I mentioned, there are no trails.

Though we couldn’t see any recent human traces, there were a fair amount of old traces: primarily, I would think, the remnants of the millionaires’ summer village. We saw wall foundations, chimney ruins, and a few big and thick rusty metal rings screwed into rocks.

This photo by Max represents the entire scene quite well: I am taking a picture of a ring screwed into a rock, with Calf Island in all its splendor in the background, and the Cheap Sunglasses riding next to it on the anchor. If you look closely (or click on the photo and zoom it), you’ll see the stack on Calf Island, and behind it — the giant white eggs of Deer Island and the Boston downtown high-rises (in 8.5 miles as the crow flies).

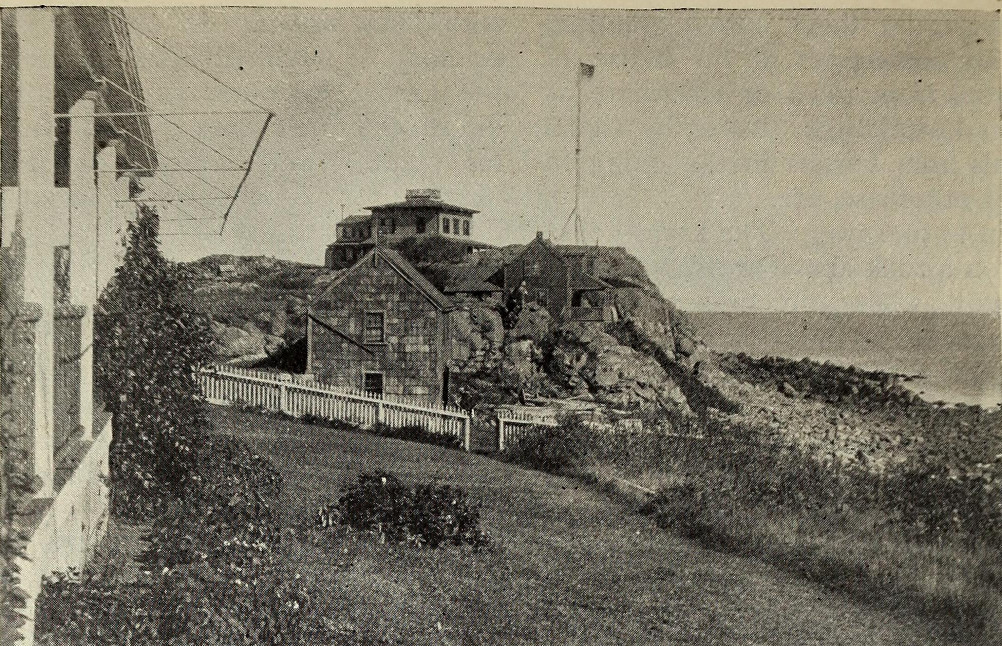

Unfortunately, virtually all photographs of the Middle Brewster village were lost — or, at least, I could not find them. Here is the only one I managed to find, from the October 1895 issue of the New England Magazine:

If you squint, you’ll see houses blending into the rocks.

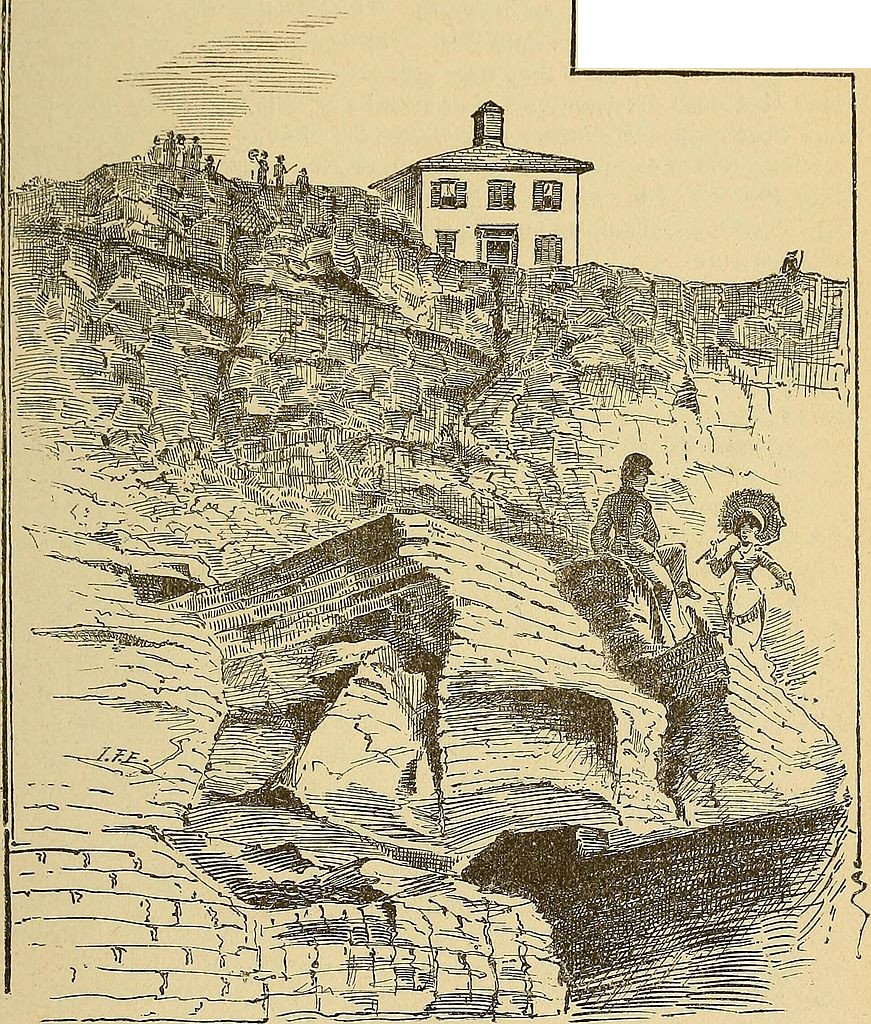

King’s Handbook of Boston Harbor (1988) contains no photos, but there is a drawing of the “Villa of Augustus Russ, Esq., on the Middle Brewster”:

It was hard for me to climb those rocks in shorts. I can only imagine how hard it was for ladies in long dresses!

From the northern side of the island we could see some great views of Boston Light and Great Brewster. Down below on the rocks there were numerous rusted structures, of weird appearance and substantial size, strewn around. I assume they were the remains of a dock or some dock-related structures. Millionaires clearly arrived to their summer houses in style — and not as we did, jumping from a rock to a rock like wild goats. But at the same time, looking at the structures, it was completely impossible to tell what their purpose was. After careful consideration we ultimately decided that they were the remains of a space station that at some point landed here — unsuccessfully.

From there, Max continued along the rocky edge to the western end of the island, and from there took a few detailed photos of Outer Brewster. The multi-color rocks of Middle Brewster are beautiful and multi-colored, but I have a hunch that the white color in particular is due to its feathered residents. Of which, as I already mentioned, we didn’t see much at all; presumably the nesting season was over.

I too followed him, but was very soon attacked by some tiny black flies of ferocious bloodthirstiness. I had to retreat. With dignity, but quite fast. For some reason, they were particularly attracted to my feet. Maybe, shorts were not a great idea after all?

I obviously had to explore the big arch — but had to do it rather quickly. Here is a photo from afar, with remnants of a chimney to the left, and Outer Brewster in the background.

And here is a photo close by.

I could never find any old photographs of the arch, nor any detailed explanation of its functional or aesthetic purpose, though I read somewhere that there was supposedly a bell hanging in there.

And from there, unfortunately, I was forced by the tiny black flies to go back. With dignity, but quite fast.

A self-portrait on seaweeds:

One of the many pictures of the colored rocks:

From there I looked down at the ocean, and was surprised to see that water was as if boiling: a big school of small fish was swimming past me. As far as I understand, in the old times it was a common sight in Boston Harbor and beyond. Nowadays it is a big rarity, of course. I mentally added that sight to the list of Middle Brewster’s wonders.

Eventually we got back to our dinghy (all oars were accounted for) and pushed it into the water, trying not to stumble on slippery rocks.

And now, as we row back to our beloved Cheap Sunglasses, I am trying to systematize and to put into words my impressions from the just explored island.

Middle Brewster is handsome in its wildness — and just handsome overall. The long-overgrown remnants of human dwellings bring the right kind of thoughts. The lonely arch, mightily and proudly rising above the thicket, symbolizes the power and the vanity of human spirit. Like on the other Brewsters, the borderline location of the island — on the line between the ocean and the harbor, the ocean and the land — intensifies your feelings. On one side, the endless water all the way to the horizon and beyond. On the other side, islands, mainland, a big city where people are busy living their lives. And you are in between, in the middle, not here and not there. Alone. Other islands are described in books and in facebooks. This island is exclusively ours.

I enjoyed it a lot.

Obviously, almost all of these thoughts apply to Calf Island as well. I just didn’t have time to think it through last night: we had to cook dinner right away.

Meanwhile we returned to the mothership. It was time to pack up the dinghy, weigh the anchor and start heading home. With yesterday’s windless weather still on our minds, we turned the engine on, raised the anchor — and then the heavens smiled at us, even wider than yesterday. There was a pretty fair wind around! Not wasting any time (but without any undue hurry), we raised our sails, killed the engine and headed back. First we sailed to the Graves Light, checked out how it was doing, then visited the red-and-white buoy “NC” marking the approach to North Channel to Boston Harbor (the same very buoy whose flashing, the letter “A” in the Morse alphabet, I saw last night), followed North Channel to Deer Island and its light, and from then it was straight home.

The ambitious part of my mind was secretly unhappy. If we only knew in advance that the forecast was lying and there was some wind in store, we could have gone at least to Marblehead, rather than to dangle in the harbor for the entire weekend.

In truth, of course, this is total rubbish. Slow life and the principle of sailing uncertainty teach us not to push our way God knows where, but rather to extract maximum satisfaction from the situation at hand. And here we are: we have visited two interesting, hard-to-access islands. Spent the night in a wonderful solitude; no way we could have gotten that in Marblehead. And then there was the sunrise, the wonderful sunrise in the outer harbor! I won’t forget it soon. And in addition to all that, we actually have done some decent sailing around the entire harbor.

Who would not get satisfied by that?

Subscribe via RSS