Deer Island

The sailing season is over.

What a pity! I just can’t make myself stop.

That’s why, when a free day presented itself in November, I mounted my bike and went to Deer Island.

Deer Island is known as the Island of Huge White Eggs, the said eggs visible from many points in the harbor and beyond, and are even charted on the nautical chart — a very rare occurrence!

It is also not an island anymore — that’s why I could ride my bike there — but it used to be. Shirley Gut, the narrow gut between the island and the mainland (the town of Winthrop to the north) was getting more and more shallow and narrow with years and centuries, and finally the hurricane of 1938 has put a sandbar over there. The sandbar was quickly paved over and made permanent, but still — Deer Island is probably the only island in Boston Harbor that stopped being an island naturally and not as a result of human activity.

(The great New England hurricane of 1938, by the way, was not a sissy: a 50-foot wave was recorded in Massachusetts, as well as a 186 mph wind gust, “the strongest hurricane-related surface wind gust ever recorded in the United States”.)

This German Boston Harbor map of 1888, taken from Wikipedia, shows Deer Island (to the west) back what it still was an island. (It also shows Castle Island and Governor’s Island when they, too, were islands.)

.jpg)

A strong headwind with blowing. The sea was covered with white caps. My frail two-wheeled vessel was close-hauled all the time, heeled hard, but still made 13 knots or so. In a couple of hours I already was at the former sandbar that the hurricane put next to Deer Island.

Standing right by the entrance to an island is always a good time to think about its history. Let us start by appreciating the sweet old-fashioned spelling in this 1634 quote from one William Wood explaining the island name’s origin:

Iland is so called, because of the Deare which often swimme thither from the Maine, when they are chased by the Woolves: Some have killed sixteen Deare in a day upon this Iland.

Beyond that, the Deer Island history is pretty typical for a Boston Harbor island. As we shall see soon, this history is not really relevant anymore, so here is a very brief list: a fort, a quarantine station (later moved to Rainsford Island), a hospital, a correctional institution turned prison.

But before all that there happened a story which still echoes till this day. Long ago, in 1675, the Massachusetts Indians (not all of them, but many) rebelled against English colonizers. That rebellion is called “the King Philip War” — King Philip is how the English settlers called the Indian sachem (chief), the leader of the rebellion. The settlers had eventually won, having drowned the Indians in blood and then having sold many survivors into slavery to the West Indies, — but also sustained very heavy losses themselves. Overall, a typical example of a peaceful coexistence of two peoples on one land.

There was one particular episode among all that bloodshed. In New England, there had been for quite some time the Indians who converted to Christianity and were loyal to the settlers. They were called the Praying Indians. After the war had begun, the government of Massachusetts Bay Colony decided that all Praying Indians were suspect — who knows what they could do! — and interned a big group of them to a concentration camp on Deer Island. As the history tells us, they were somewhere between five hundred and a thousand people, mostly women and children.

And having interned them there, “the authorities” didn’t bother to feed them, or to clothe them, or to keep them warm. During the winter of 1675/76 at least half of the prisoners died of cold and hunger. After the war the surviving Praying Indians were allowed to leave the island. Some of them, though, were sold into slavery — just so, for no reason whatsoever, as Christian people are supposed to treat each other. No doubt that the proceedings had helped the budget, too.

This story also surely teaches us some kind of a lesson. Perhaps this: how much it really helps you to yield and to accept the occupier’s religion.

The descendants of the English settlers, the modern Americans, have long ago forgotten that small episode of a distant war. But the descendants of the Indians, the modern Native Americans, still remember it well.

Now we are skipping to the 1980s, arguably the most important time in the island history.

In the seventies and the eighties Boston Harbor was not just dirty: it stunk. My sailing friend Liz, who started sailing back then, told me that the water in harbor at the time was brown, and one could catch all kinds of interesting diseases just by putting a hand in the water. Just one fact: lobsters in the harbor were contaminated so much that it was illegal to even catch them.

As the Massachusetts government was chronically unable to fix the situation, the concerned citizens ended up taking them to court. The legal history of what happened then is somewhat complicated. There were two great judges involved: Judge Paul Garrity of Massachusetts Superior Court, and U.S. Federal District Judge A. David Mazzone (Wikipedia conflates them).

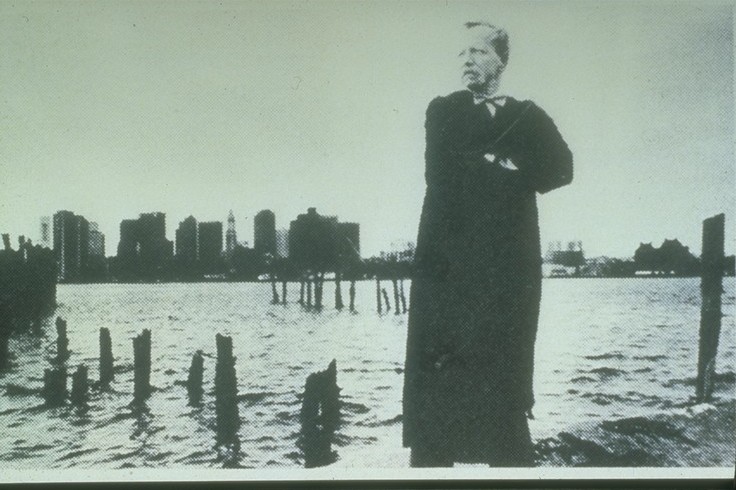

Judge Garrity, as he was handling the case, posed for a The Washington Post photographer with the backdrop of the decaying harbor. That photo, later reprinted by The Boston Globe, had made a strong statement: this was not how judges were customarily portrayed back then.

Deer Island had a pumping station then which was pumping waste waters into the harbor. Judge Garrity was known to come there and introduce himself to the station workers as “sludge judge”. The name stuck.

After the state case was over, the federal case was allowed to proceed. The net result of both courts’ decisions was to force the State of Massachusetts to clean up the harbor. It sometimes happens in America that courts force the government to be decent. The political right calls it “judicial activism”. I refuse to be drawn into political or judicial debates, but I am convinced that in this particular case Judge Garrity and Judge Mazzone deserve a memorial in Boston.

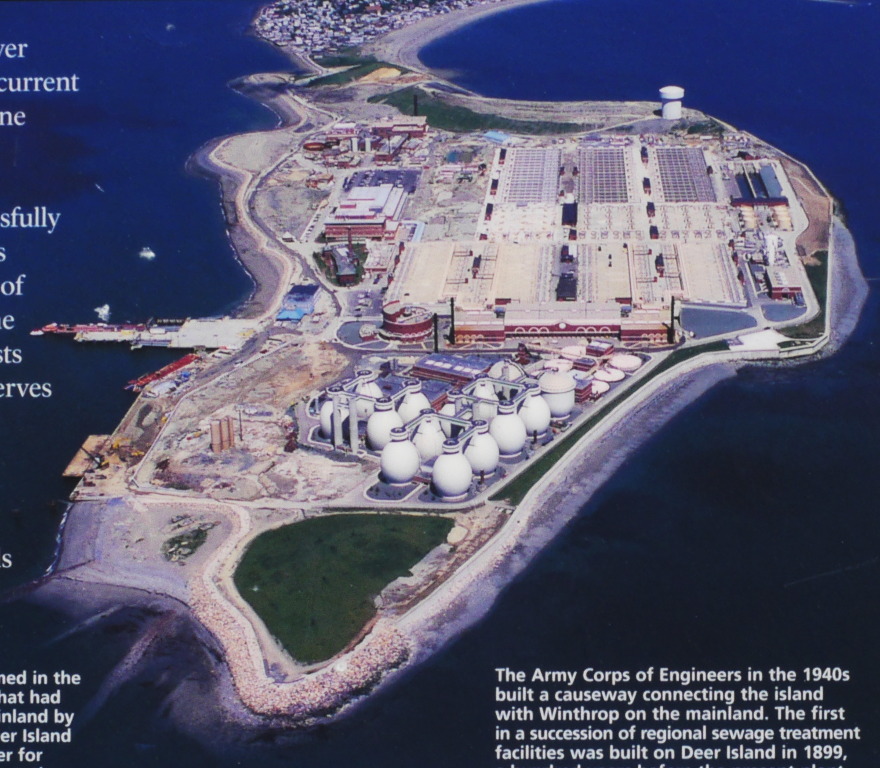

The courts came to the conclusion that it was illegal to dump sewage into the harbor. A huge modern waste water treatment plant was built on Deer Island in 1985–2000. The sewage water is purified there to the state close to drinking water, and then pumped into the ocean via underwater tunnel 10 miles offshore, away from the harbor. Upon the completion of the plant, untreated sewage is never dumped in the harbor under any circumstances.

The Deer Island plant is the second largest sewage treatment plant in the United States. The tunnel is one of the longest tunnels in the world.

But much more important is that Boston Harbor turned into the harbor we all know and love: one of the cleanest in the US, with pure emerald water, in which it is a pleasure and a joy to swim and to sail. Thank you, Judges Garrity and Mazzone, for single-handedly cleaning the harbor and improving quality of life of millions of people.

The plant construction project has transformed the island entirely. All the existing structures, including the prison, were demolished (the inmates got transferred to other prisons on the mainland). A hill on the island was moved towards the neck to shield the town of Winthrop from the plant, and then some walking paths were established on the hill. The former site of the hill was leveled, and that same waste water treatment plant was built there. There are no more deer on the island, nor any wolves in Winthrop.

Native Americans consider the island to be sacred: many of their ancestors had perished there. For many centuries all traces of the concentration camp had vanished too, but now even the ground itself have changed. They tried to protest, but to no avail. You can’t stop progress.

Nowadays, some of them wander around the island and claim to hear voices of their ancestors. Island visitors (joggers and dog walkers) and the workers of the sewage plant don’t confirm that. They don’t hear voices.

The political impact of Native Americans is approximately equal to zero, but when they make enough noise, the powers that be can take a notice and make a small, insignificant gesture. For example, there exists a plan to build a memorial on Deer Island. In fact, it already existed for many years… let’s see what happens.

As I am entering with my bike the parking lot by the island entrance, it is time to jump forward to the present day, a windy November afternoon.

My plan for the previous summer (and many coming summers) was to explore the Boston Harbor islands unreachable by ferry. Formally speaking, Deer Island fits the bill: ferries do not go there anymore. They used to, and the dock is still there. But after September 11, 2001 the ferry service got canceled. The dock — and the plant itself — were hidden behind a tall fence, and there is no going there anymore. Why would terrorists want to blow up a shit processing plant, and why would they necessarily need it to do it by boat, I have no idea. Maybe that’s why I am not a terrorist a politician. But, practically speaking, I could get there only by bike — and there I was.

The weather was very visual: powerful west wind, white caps in the ocean, high waves breaking with thick spray against the wind, sun and rain replacing each other as in kaleidoscope, and between them the sun beams coming out of the clouds and painting the universe in bands of all possible shades of yellow.

Out of all (former) islands reachable by land, Deer Island kept the most that special feel of an island, an outpost between the harbor and the ocean, with boundless expanse of water to the east, the invariable outlines of the city and the airport to the west, the constantly varying composition of other islands to the south. That day, the beautiful and wild weather multiplied this feel over and over, underlined it and put an exclamation point. We are on the island, the mainland laws don’t apply here.

I fully admit that the Cyclopean structures of the sewage treatment plant distract the eye and break the proper mood. But really, one doesn’t have to look inward.

Sailors always look outward. That’s why they see the world better, more faithfully than the landlubbers.

For this report, however, I looked both inside the island and outside. All that remains is to show you some photos.

The aerial view (from a placard on the island). On that photo the plant is almost finished, though clearly not entirely so. We are looking, more or less, from south towards north.

Entering the island. A road in place of the sandbar put there by the hurricane many decades ago.

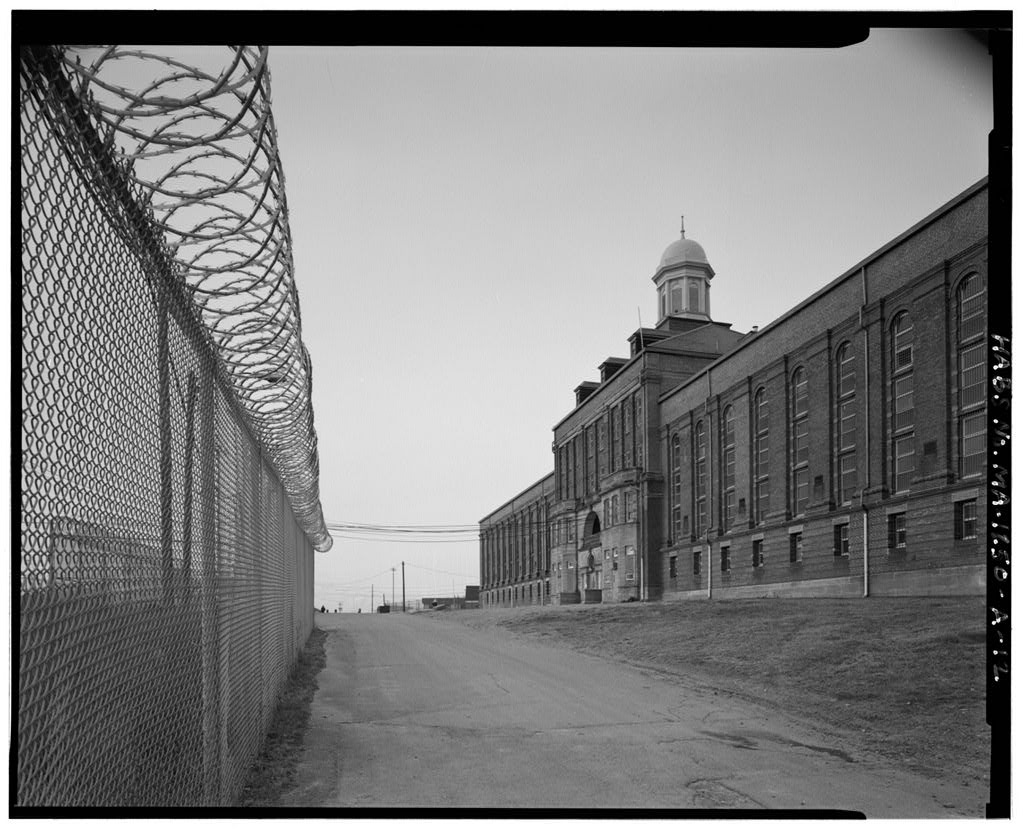

It was not easy to find this old (undated) photo of what that road used to look like. Deer Island, with its prison, is in the background.

At the very entrance to the island two authentic buoys are placed, green and red. Placed, unfortunately, in a wrong order: the red should be to the left when entering the island, and to the right when leaving (the mnemonic rule: red right returning). I am a perfectionist, and such inattention to details deeply disturbs me.

A great view towards Boston right from there. It somehow represents well that day’s weather.

A view across the water at a colorful part of the nearby town of Winthrop, with the water tower painted in the Russian American flag colors. I know that water tower: it is well visible from the sea and as such is frequently used for navigation.

By the way, speaking of airplanes. Logan International Airport is situated exactly between Deer Island and downtown Boston. When the wind is right, the planes approach from the ocean, past the island. They do it so often that become an essential part of the landscape.

Planes are not really my cup of tea, but it is what it is.

It’s the fall on the island.

As it is impossible not to notice planes, it is even more impossible not to notice the ocean. It surrounds you from all sides, takes you in, overpowers with its greatness.

Ships on the horizon in the general direction of Spain.

Greater Brewster Island, which we explored that summer, and Boston Light nearby.

And, of course, one cannot miss the elephant in the room — the waste water processing plant. It processes sewage from 43 cities and towns in the Greater Boston, about half the population of Massachusetts.

The most obvious feature of the plant — giant white eggs (even though, if you look carefully, you’ll notice than two of them are giant white acorns). The eggs are called “digesters”.

The eggs output methane gas (used to generate heat and electricity) and sludge processed further for fertilizers. What the acorns are is less clear. Jeremy thinks that they are used to store methane.

One of the numerous placards on the island proudly proclaims that these eggs are the first thing visible when one approaches Boston by sea. I am far from disputing the importance of eggs for marine navigation, — but really? Are we proud now that the first visible part of our city is vats full of shit?

On the other hand, let’s admit: if not for the eggs, all that stuff would be floating in Boston Harbor, spreading stench and diseases. The eggs show the triumph of man’s instinct of self-preservation, so rare these days.

OK, I am convinced now. Let’s be proud!

And as a small illustration, this is an actual view of the southern approach to Boston. Foreground: Minot Light; background: to the left of the light, the control tower of Logan International Airport; to the right — well, the eggs.

What is this? An abstract sculpture, or a technological part of the plant?

For many years we would sail past the island and wonder what is the thing on the photo below. Inspecting it in person didn’t provide any clarity. The only reasonable theory I heard was that it was a wind generator.

On one hand, I never ever saw it spinning.

On the other hand, how many things in our life are never spinning?

This is a wind generator, for sure.

Overall, the Deer Island plant is one of the major energy consumers in New England, and they have all kinds of projects to produce some of that energy themselves: wind mills, solar cells, burning methane produced by the plant.

I kept telling you about that day’s weather, but hardly showed any pictures. That’s because I look at them now, and see — they are all off. A pale image of the real thing!

Just trust me, the weather looked gorgeous.

Deer Island Light

Just a small note on the topic on marine navigation.

In 1890 a nice small lighthouse was built next to Deer Island. The great Joshua Slocum mentions it as a first landmark and navigational aide in his circumnavigation (1895).

The reason why I never mentioned it among the lighthouses of Boston Harbor is this: In 1982 the lighthouse, long automated and deteriorating with years, was demolished and replaced by this structure:

The new structure resembled a candle. It least, I think so, some people have different associations. But definitely not a lighthouse anymore, or so I thought.

This time I changed my opinion and was going to recognize it as a lighthouse, take better pictures, add to my own list of Boston, tell you its entire story.

And what do I see?!

The candle is gone, and there is quite a frivolous structure instead. Clearly not a lighthouse!

Very disappointing. But I eventually did write down story of the lighthouse.

(The candle photo was taken from Deer Island in summer 2013, when a long bike ride with my lovely daughter brought us there.)

Back Again

The preceding report is based on the trip I did back in November 2015. This January, Jeremy and I have paid another bike visit to Deer Island.

This time, the weather was unseasonably warm, and quiet. There were many more people on the island, so we can do some people watching. Here, one girl is relaxing after jogging, and another one does some bird watching.

Being kept away from the water off-season, I often imagine that the ocean is covered with ice, and all shipping ceases to exist. Lo and behold, life doesn’t stop just because I am not watching, and large container ships are still heading to Boston Port.

Last time I neglected to take a picture of the memorial to Judge Mazzone, put to the backdrop of the Boston skyline and the airport. The quote from his famous legal ruling reads, The law secures to the people the right to a clean harbor. As you remember, there were two crucial judges in the battle for a clean harbor, but that apparently turned to be too many to memorialize. Judge Garrity, the Sludge Judge, will have to do without. You have read it here, please remember him as well, and keep thanking him for Boston Harbor together with Judge Mazzone.

There are many benches on the island, and every single one is dedicated to somebody. There is clearly a story to it, but I couldn’t find it anywhere.

Most of the benches just have a small memorial plaque, and leave it at that, but some of them up their game very seriously with seasonal decorations (that was back in November) and little angels.

This is the only old building remaining on the island: the late nineteenth century pumping station, now the plant’s visitor center (they offer free tours, but somehow I never was in the right mood for a sewage processing tour).

Jeremy takes photography seriously.

On our way home we decided to try something different, and took East Boston Greenway, a nice and relatively new bike path — well, at least new to us — all the way to the end. It deposited us not far from the Shipyard and Marina in East Boston.

This happens to be the very shipyard where the famous Boston shipwright Donald McKay (1801–1880) built his ships. We talked about the shipwright and the shipyard in the story of Castle Island. I showed you the large-scale art installed right there, depicting McKay’s famous clipper Flying Cloud (the world record for the fastest passage from New York to San Francisco) next to, one would assume, Boston Light. Or maybe not. This particular artistic style does not dwell on slavish realism.

Right across from the art is KO Pies, a well-known locally Australian pie joint, where we just had to pay a visit. In addition to decent pies, their bathroom surprised me by the wealth of old Soviet propaganda posters (and yes, I felt awkward visiting the bathroom with a camera). For example:

It was getting dark fast, and instead of biking back through the industrial wasteland of the fair town of Everett, we hailed a water taxi and sailed right from the marina to downtown Boston, straight into the fading sunset.

Taking a boat to come back from the island felt right.

P.S. After writing and posting this post, in February 2018, I was taking off from Logan Airport, and Deer Island happily presented itself:

Left to right: the South part of the town of Winthrop with a harbor and the distinct tri-color water tower; the neck leading to the island (former Shirley Gut); the hill at its new location; the plant; the huge white eggs.

Subscribe via RSS