Weekend at the Outer Islands

This trip took place in October 2017.

Day 1. Calf Island

As it often happens to me, I panicked at the end of the season. This is it, the end, you can almost touch it, not only the summer is long gone, but even the fall is essentially over — while so many things are not done yet! So many plans are not realized!

This is why, on that penultimate weekend of October — the penultimate weekend of the sailing season — it was decided to go sailing overnight.

The weather was forecast warm and dry: excellent weather, no doubt, just not very windy. When I stepped out in the morning, the entire nature was frozen still. Not a single leaf on a single tree was moving.

As I said already though, we couldn’t back down no matter what. I decided that we would unhurriedly motor to one of the inner islands in Boston Harbor — say, to Bumpkin Island; land there and explore the island; then will spend the night anchored, and next morning will slowly return home. The plan was, no doubt, not very ambitious. But at least it was realistic.

And then, as we were coming out of the inner harbor, the heavens had smiled at us: a wind had picked up. Not the strongest wind I’ve seen in my life, but quite workable.

With the feeling of deep satisfaction we raised our sails, killed the engine, and started sailing. The wind direction made Bumpkin somewhat awkward to reach, so we decided instead to head to the two Outer Islands where neither of us had been before: to Calf and Middle Brewster islands.

On our way, we’ve met a seal. I knew that they live in the harbor, but rarely encountered them. And here, at the end of the season, they finally decided to pose for a photo!

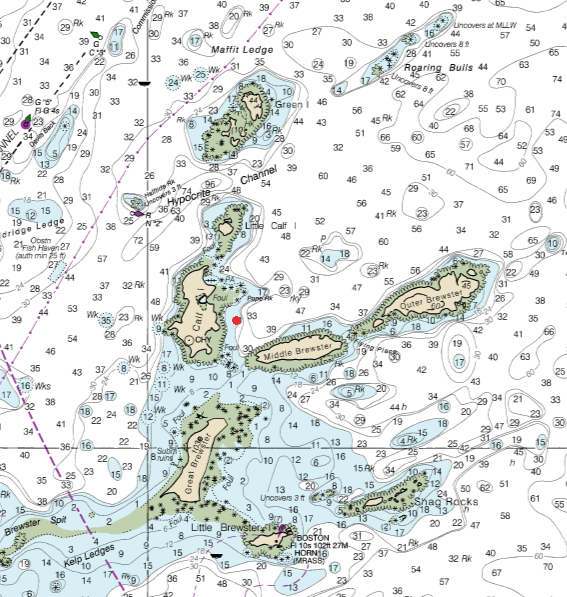

Meanwhile, we had reached our destination, and it was time to drop an anchor. Anchoring by the most of the outer islands is a big headache. First of all, there are rocks everywhere. You’d really want to place the boat so that the wind would push her away from the island, and not at a rock. Not to mention that if you actually going to sleep on the boat, you want the island to protect you from the wind and the waves. Second, in most places it gets deep really fast: too deep for anchoring. Again, one ends up looking for shallow enough places close to the rocky shores.

This time we first tried to tuck behind Middle Brewster: it provided reasonably good protection from the wind. According to the chart, there was exactly one spot suitable for anchoring, but it ended up being uncomfortably close to the shore. What if the wind changes overnight? Especially since the tide was going out?

So, we abandoned our attempts at Middle Brewster and moved over to Calf island, and there barely found a workable place between rocks. By that time the day was already waning, and we could not waste any more time. We inflated the dinghy, and set out to explore Calf.

As we are working the oars rowing from the anchorage towards Calf Island, the time has come, first of all, to show it to you. This is how we saw it in October one year prior from a hilltop on Outer Brewster:

Most sources don’t explain the origin of the name, Calf Island. I always assumed that it was named after the animal. There are a few other places like that in Boston Harbor: for example, Roaring Bulls (partially submerged rocks nearby), or Sheep Island. Edward Rowe Snow, however, writes that the island was “probably” named after one Robert Calef, “prominent in the early Boston and in Lynn history”.

After Calef, the island belonged to this serious man, Charles Apthorp (1698–1758), “in his day called the richest man in Boston”.

It is also possible that it was not Apthorp himself who owned the island, but rather his daughter, the beautiful Susan Apthorp (Snow hints at that). In any case, for some time the island was called Apthorp Island. Its another old name was North Brewster, in addition to the four other Brewsters in the vicinity: Great, Middle, Little, and Outer.

Calf Island’s main feature, visible from afar (and easily discernible on the photo above) is the tall brick chimney stack, growing as if out of nowhere. This stack is all that remains from a luxurious mansion of the Bostonian millionaire and the railroad tycoon Benjamin Pierce Cheney, Jr. (1866–1942), and of his wife, the famous theater and silent movie star, the also beautiful Julia Arthur (1869–1950).

The happy couple bought the entire island, and built there, in 1902, a huge mansion: 20 rooms all in all. They had eight servants to take care of the mansion; the servants had a separate house. The mansion was called The Moorings: obviously, every respectable mansion should have a name.

And so they were leading a dream life until 1917, when Cheney went bankrupt. The mansion was then auctioned off, and things went otherwise awry for the couple. Julia Arthur, by that time having retired from the stage and invested her creativity in treating guests in the mansion, had to go back to the theater and start earning her living. Cheney’s end was even worse: he died of thirst in 1942 in an Arizona desert. Very impressive poetic plot twist: you start as a millionaire, live in a 20-room mansion on your own island, and then die because there is no one out there to pass you a glass of water. (Clearly, the universe is trying to send us a message here.)

Meanwhile, the mansion together with the island was ultimately acquired by the federal government, who had planned to build some defense facilities there. The First World War was going on; clearly, there was need for defense.

Those plans had never come to pass, however; and the magnificent mansion, let us say, went somewhat down over the past hundred years.

Calf Island, like most of the other outer islands, is made primarily of rocks and stones. It was not easy to find a good landing spot for the dinghy. We couldn’t see any on the island’s east side, where we dropped the anchor.

We headed left, turned around the corner and came over a rocky beach surrounded by more rocks in the water. That was not ideal (we had to wet our feet), but perfect is the enemy of good, and all that. We landed, and carried the dinghy inland, away from the coming tide. (As we explored the island further it turned out that there were a couple of more beaches on the west coast that looked more amenable for landing. Writing it down here to remember in the future.)

From the beach, there was a trail uphill. We followed it, and as we went, saw a few traces of human presence: grill fire pit, firewood, chairs. There were no people on the island, though; we were alone.

Continuing up, we eventually reached the mansion ruins. Out of them, a magnificent chimney stack rose up — the one that can be seen from afar. Some good people leaned a tall ladder to it. We didn’t rise to the challenge.

Originally, there were two stacks here: there are two charted on my twelve-year-old paper chart. But then came bad, evil people, and destroyed one of them. Sooner or later, they will destroy the other one; the entropy always wins. That’s why there is such an urgency to explore our islands. The time doesn’t spare them.

Following the trail from the house ruins, we came over the ruins of some kind of porch, or an observation deck, hanging high above the shore. I had no idea it was even there!

From the deck, there opened an impressive view of Boston Harbor and the city of Boston itself (in eight miles from us as the seagull flies) — the view made even more impressive by the sunset colors. I couldn’t stop myself from imagining the scene here a hundred years ago, when elegantly-dressed imposing ladies and gentlemen were lazily sipping their cocktails here. On the other hand, there were no skyscrapers in Boston back then, so presumably the view was a little bit less striking.

The trail meanwhile had passed through the high thicket of staghorn sumac (above our heads), went down to the shore and brought us to the ruins of a dock. There was preciously little left of the dock, though, — just a couple of posts.

With that, the trail was over. We, obviously, didn’t stop there and continued with the island circumnavigation, jumping rocks here, squeezing our way through a thicket there. As many other islands in Boston Harbor, Calf Island consists of two hills connected with a narrow neck. On the neck, we found tidal pools, marshes, and a little fresh-water pond. At least, the internet says it was fresh-water; I didn’t verify that.

Making our progress down the eastern part of the island, we kept seeing the Cheap Sunglasses, our sailboat, riding on the anchor. She kept her position well and stayed away from the rocks. To me, it is always important to keep an eye on the anchored boat; it gives me peace of mind.

Having closed the loop around the island, we came back to our inflatable dinghy. She was peacefully resting on the rocks where we left her, and that also gave me peace of mind. The last flashes of sunset blazed over Boston, and I took a couple of last pictures.

However, as we got to the dinghy, the piece of mind was shattered by a frightening discovery: one of the two oars was missing! We soon found it floating in the water between rocks, but it all made a strong impression on is — like what Robinson Crusoe felt when he stumbled upon a human footprint on his uninhabited island.

(Later, we careful reviewed our photos and came to the conclusion that we dropped the oar ourselves during the landing, and there was no reason for concern — except for the concern for our own sloppiness.)

As we rowed back to our mother ship in the dusk, we encountered a family of seals resting on the rocks. They swam away as we were approaching, but that definitely was our seal-lucky day!

It was too dark to take pictures, but it didn’t stop Max from doing so.

Then there was the dinner in the cockpit, in the darkness between the islands, with the traditional rum for desert. Another sailboat, anchored earlier in the distance, had raised her anchor and sailed away. We were alone.

A remarkable calm and tranquility filled the space around us. As if we were not in eight miles from downtown Boston, but rather in a different world; and if it were alien spaceships flying by, rather than lights of the planes approaching Logan airport.

I went to sleep in the forward cabin, but woke up in the middle of the night, and felt an irresistible urge to go to the deck and breath fresh air.

So not to go through the entire boat and wake up Max, I managed to climb up through the hatch right above my bunk. It was warm enough to stand on the deck barefoot. The boat laid quietly at the anchor. The islands were surrounding us, black lumps against the black sky. Towards west, the sky was slightly yellowish, lit by the lights of Boston hidden from us. Behind the clouds, I could see some bright stars; Orion and Sirius shone clearly in south west. The planes were not flying anymore, but the lighthouses were flashing. The bright light of Boston Light was very close, flashing every ten seconds; further away there were the lights of the Graves, Minot, and the red and white buoy at the entrance to North Channel. The lights of two big container ships anchored offshore loomed on the horizon.

As the water and the sky always blend together at night, so the heavenly stars blended in my eyes with the flashing of distant lighthouses, and I felt surrounded all over by lodestars.

At the same time, besides Max, who was sleeping peacefully down below, there was not a single living soul around me, just the black outlines of the nearby islands. It was very easy to imagine how there were sailors anchored here a hundred, and two, and three hundred years ago, and how they felt here without the internet, and GPS, and smartphones.

And that’s how that first day came to an end.

(Continued here.)

Meanwhile, let’s look at some pictures.

The only traces of human presence: BBQ and some chairs. The chimney stack is ahead, behind the trees.

Here it is, the magnificent chimney stack. I stand corrected, here is one more trace of human presence: somebody not lazy brought this enormous ladder from the mainland. We chose not to climb it.

Next to the ruins there grew a few trees with small red fruits, sour in a good way. Back then I had decided that those were small wild apples, but apparently they were not apples and not wild — but rather cherry trees planted by the mansion owners.

The ruins of the observation deck/gazebo, called in English by an Italian word belvedere:

And the view from there:

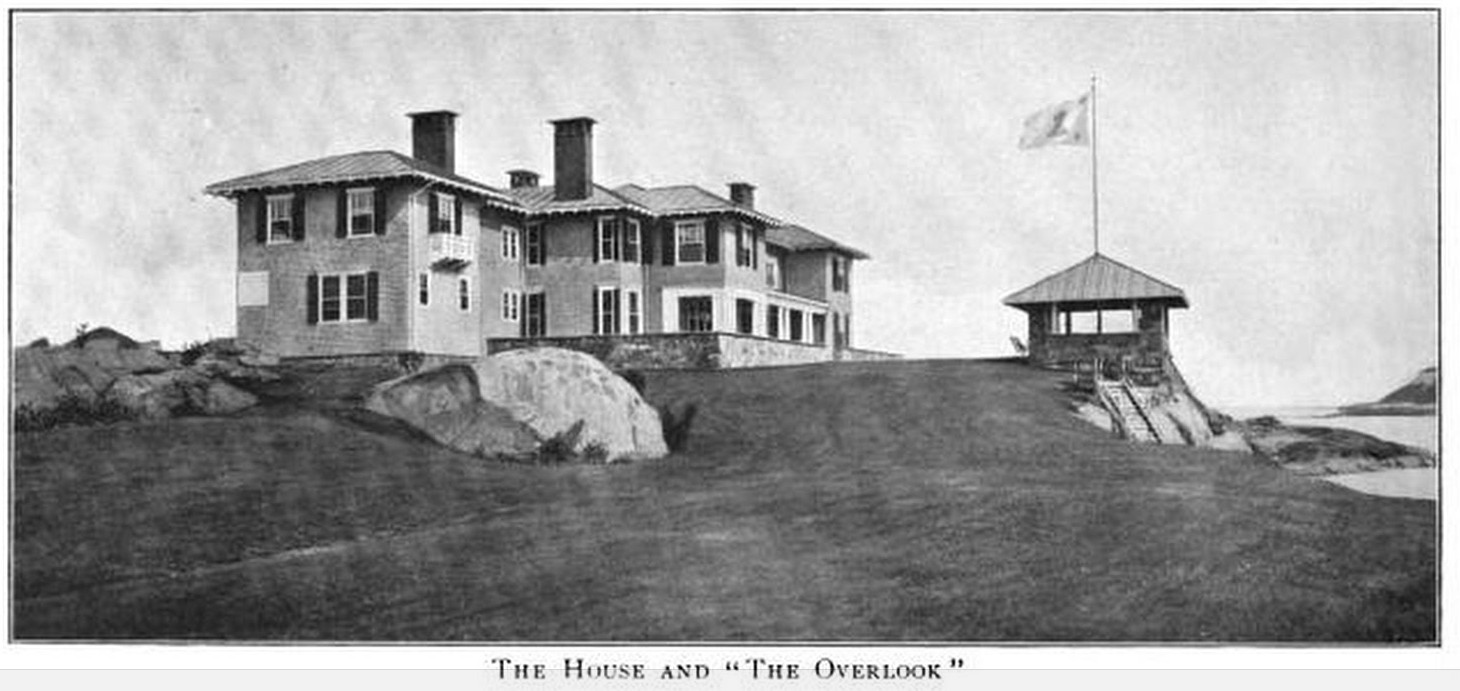

Now it is time to slow down, close the eyes and finally imagine to ourselves how all that luxury used to look when it was still luxury and did not lie in ruins. So: it used to look approximately like this:

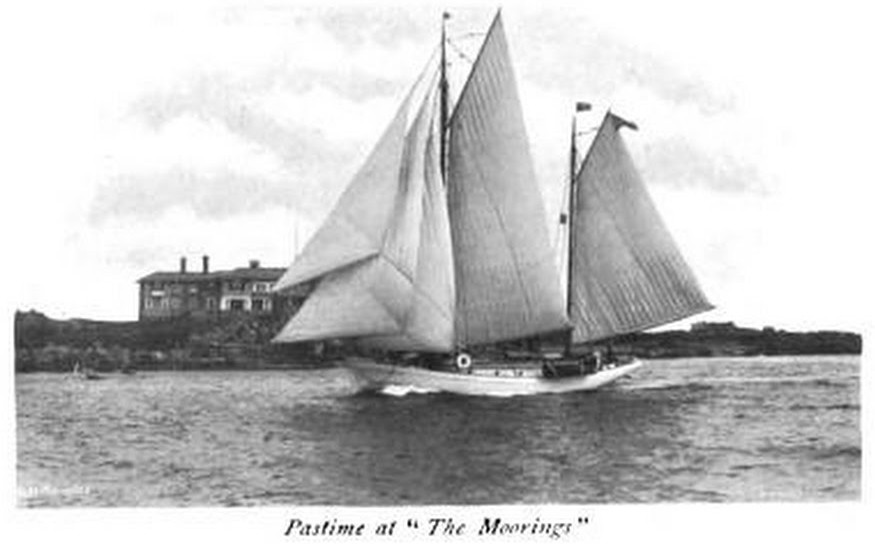

I took this photo from an edifying article in the May 1906 issue of Indoors And Out, “a Monthly Magazine devoted to Art and Nature”. “This house”, begins the anonymous author, “is designed for a hot weather refuge for a busy man of affairs and his family. The whole island is under his sole control and can only be reached by his yacht.” The yacht photo, captioned “Pastime at ‘The Moorings’ ”, is attached right away:

On both photos, you can clearly see the two tall chimney stacks.

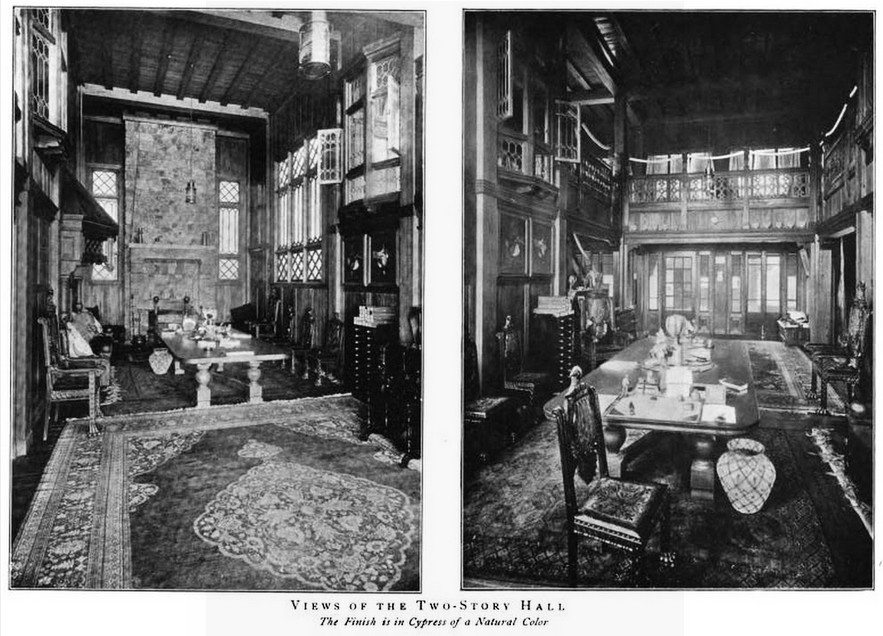

The article contains quite a few photos of the inside furnishings. For example, here is a two-story hall finished in cypress:

Note the carefully trimmed lawn on the first photo from the article. Now it’s all overgrown way above my head:

Meanwhile, we keep walking around the island. The remnants of the dock with Great Brewster Island in the background:

The sun setting in the shrubs:

To the north of Calf Island, there is another, little island, called obviously Little Calf Island. We didn’t visit it yet, and it’s not clear to me if it is possible to land there at all: the entire island consists of rocks (or, rather, one big rock). Behind Little Calf you can see Graves Light and a couple of container ships anchored off shore.

And here we can see again our old friend the Cheap Sunglasses.

A little pond in the middle of the island. The city and the sunset are in the background.

Sunset over Boston, in more details:

The dusk is descending and the lighthouses are lighting up around us. This is Boston Light behind Great Brewster Island:

Our dinghy is waiting for us patiently. Too bad we’ve lost an oar, but doesn’t matter, we are bound to find it again!

(Continued here.)

Subscribe via RSS