Minot's Light

New England lighthouses, — they are like milestones marking the explored space, our ecumene.

Lighthouses are first to appear on the horizon. They bring hope to sailors’ hearts. You are not lost hopelessly in the endless waters, they say. If you need help, we shall help you.

Most lighthouses are built on firm land. Next to it is a keeper’s house. Maybe there is even a road leading to it. Before they were replaced with machines, the lighthouse keepers used to live there, go shopping, entertain visitors.

Minot’s Light is not like any other. It grows straight from the ocean waters. Not on an island stands it, unlike Boston Light. Not on rocks, unlike Graves Light.

No, like the finger of Providence it sticks straight from the Atlantic, stands, unshakable and proud, up to its full 114 feet height among the waves. While other, lesser lights can get obscured by shore here and there, Minot’s is visible from every direction, loud and clear.

One who meets it will never forget it.

A Man With a Dream

If you sailed with me, you probably met Sergey, my frequent first mate. Well, for years now Sergey had a Great Dream: to meet Minot’s Light close and personal. And for years, no matter how hard he tried, that dream was being thwarted. Sometimes, the wind would not cooperate. Sometimes, the course would be at a distance from the light. Sometimes, we would pass it at night, in complete darkness punctured by the light flashes.

The unrealized dream weighed heavily on Sergey. I could see him smile less, withdraw, even stoop as he walked.

It all changed in early May.

Before that, on May First, we had opened the sailing season, as we do every year, but there was no wind, and the opening felt somewhat forced. A sailboat with no wind is like a bike with no pedals. It feels good to spend time in it, but it’s hard to shake a feeling of missing something important.

Well, that day in early May was something else. The forecast listed strong westerly wind with gusts up to thirty knots, sometimes even mentioning the invigorating words gale warning.

There were four of us: Lena, Ben, Sergey, and I — and we all agreed that that was the day to make Sergey’s dream come true, to go and see close the great and stern Minot’s Light. That’s why friends exist, to make friends’ dreams happen.

The day, after all, could not have gone better. There was no gale and no storm, the thirty knot gusts did not materialize either, and the day was like a typical good day in Boston: strong wind; light wind; wind, shifting all the time for no reason (all mixed up well, to keep us guessing); — but also the sun and the ocean all the way to the horizon.

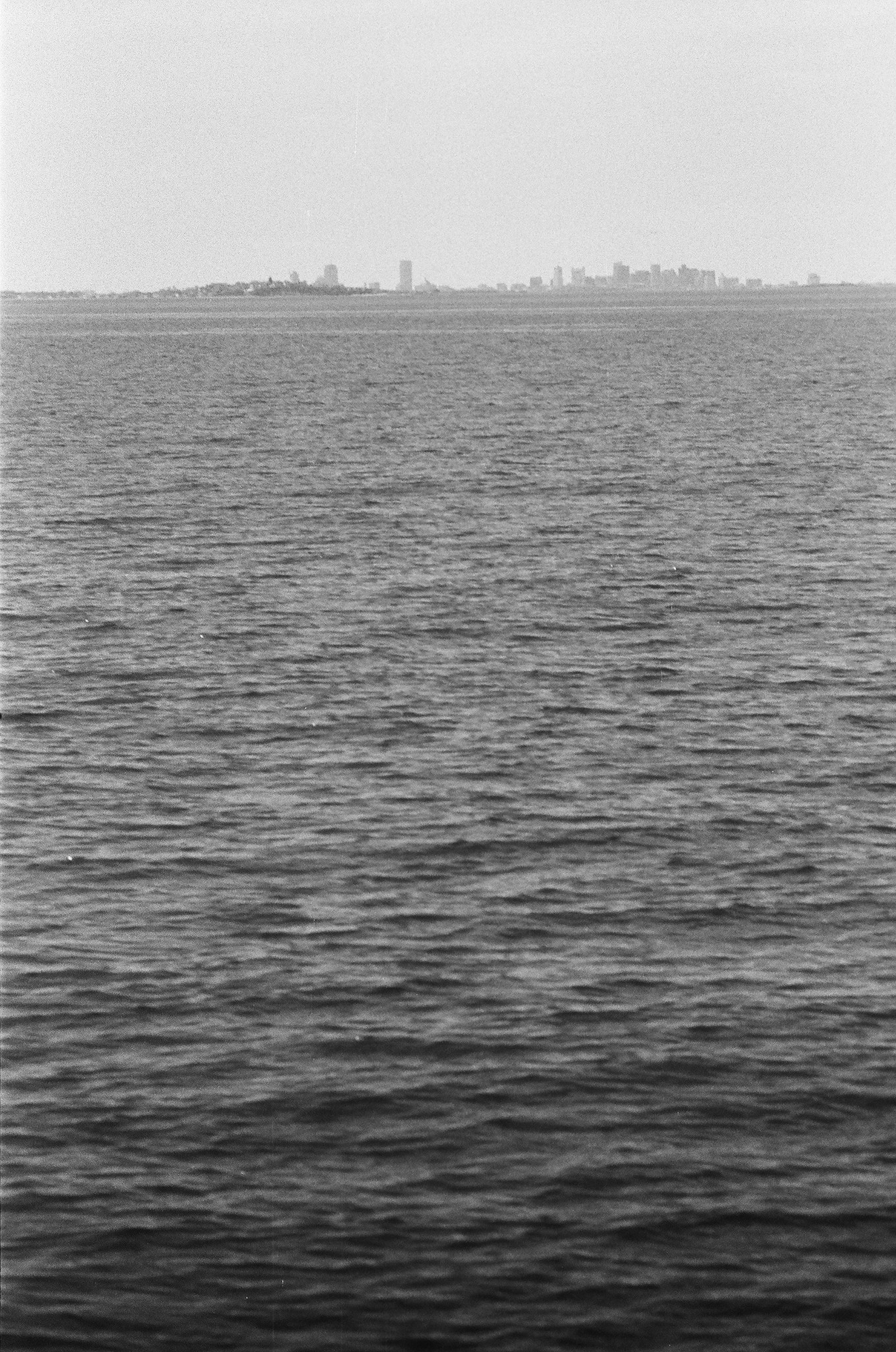

So, as agreed, we sailed out of Boston Harbor, and turned towards Minot’s Light, a little bump on the horizon, watching for the next two hours as it was magically growing out of the sea water.

I had with me an old film camera with a roll of black and white film, and that old-fashioned technology was a great match to Minot’s Light’s character.

Between the lighthouse and the shore there were a lot of rocks, both underwater and above water, from which it protects ships and boats. We, obviously, didn’t go there, but some of the rocks were visible from afar and reachable with a zoom camera.

In two hours, we were already at Minot’s, enjoying its company — and I hope that the feeling was mutual.

This is the lantern room, which houses the actual light and the optics.

Sergey was ecstatic. This was like a dream come true… scratch like. Just the dream come true.

After we went around Minot’s Light (being careful not to end up behind it, on Minot’s Ledge), it was time to air-kiss it for one last time and turn back, towards Boston. We had to go against wind and tack our way back; accordingly, it took longer, and we had plenty of time to enjoy the misty, almost unreal distant skyline.

That day came out just great. Ten hours on the water (four hours on the way out, and six for the way back). That felt like a real season opener.

But most importantly, we helped Sergey to fulfill his Great Dream.

And that, my friends, is worth a lot.

Spidery Tower

Now, after we visited Minot’s Light, it is about time to tell its story.

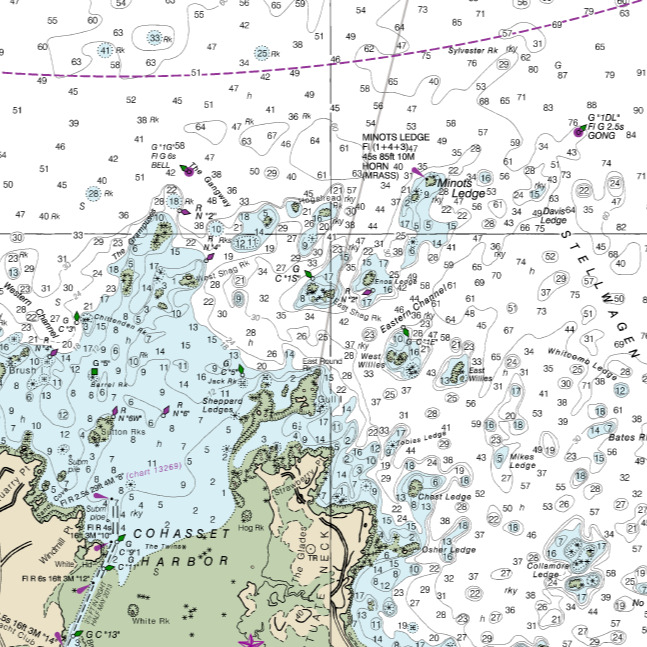

The Minot’s Light (full name: Minot’s Ledge Light) stands on submerged rocks which are called Minot’s Ledge, about a mile offshore from a little coastal town of Cohasset. The waters between Cohasset and Minot’s Ledge are full of dangerous rocks, submerged and not:

The rocks are called Minot’s Ledge after George Minot, a well-to-do Bostonian of mid-eighteen century: his ship had wrecked on these rocks long time before the lighthouse was built.

Since then, shipwrecks happened here often. Lives were lost. In 1847 the Congress had finally budgeted the construction of a lighthouse.

The construction started the same year. The problem was non-trivial: the lighthouse was to be built on underwater rocks. More so, it was to be the first lighthouse in the US entirely surrounded by water.

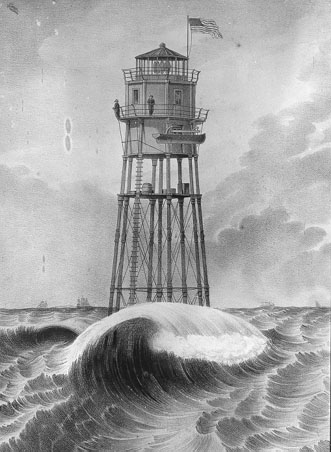

Eventually, a spidery design depicted here was chosen. It was assumed that the waves would pass through its 60-feet-high legs unhindered.

The Coast Guard considers the day when a lighthouse was first lighted to be its birthday. Minot’s Light was first lighted on January 1st, 1850.

Minot’s Light’s keepers had to live right inside the lighthouse: there were absolutely no way to build a separate keeper’s house. The very first keeper was convinced that the lighthouse was not safe. He kept sending reports to that effect, and kept getting responses that the lighthouse was designed to stand for centuries. In a few months he resigned, together with his two assistants.

His successor, the second keeper, was an old sailor: Captain John Bennett, former first lieutenant of the British Navy. Bennett looked at his predecessor’s fears with disdain. He hired two new assistants, two young fellows: an Englishman, Joseph Wilson, and a Portuguese, Joseph Antoine. (According to the rules, at least two people had to be present at the lighthouse at all times.)

The winter of 1850–51 was harsh. Storms, heavier and heavier, kept hitting the lighthouse. Captain Bennett had changed his opinion. He too came to the conclusion that the lighthouse might not withstand it. He too started filing reports to the headquarters.

The headquarters finally sent a commission to evaluate his concerns. It just so happened that the day when the commission visited the light was dead still. The commission reported that the lighthouse was absolutely safe.

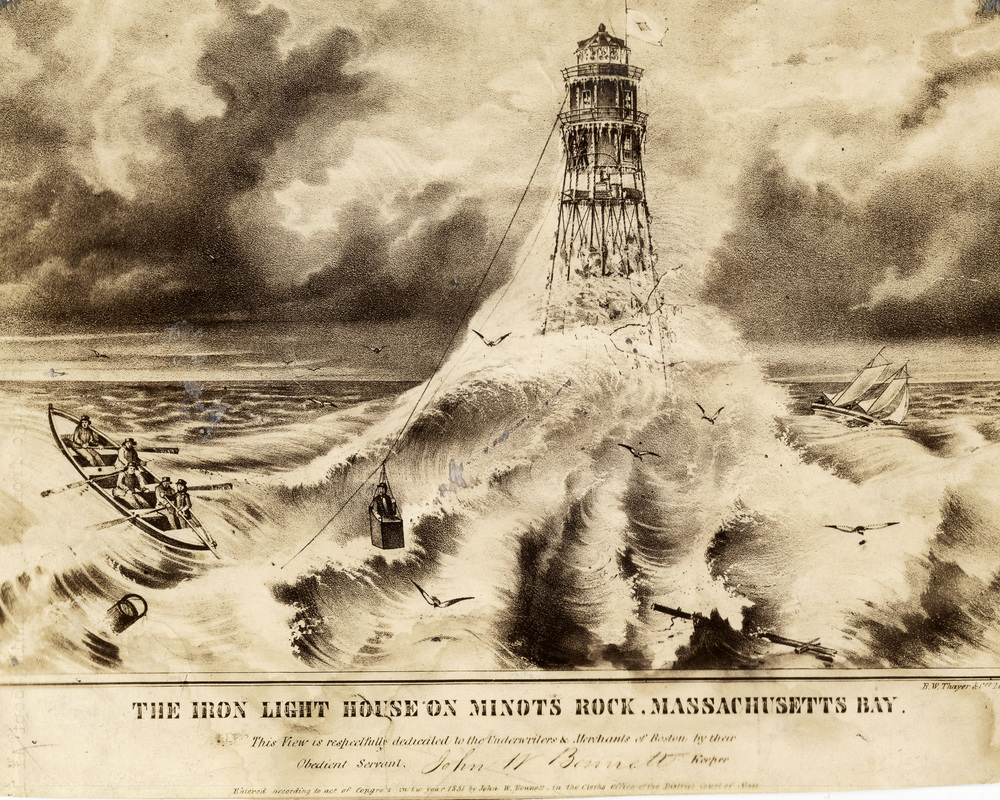

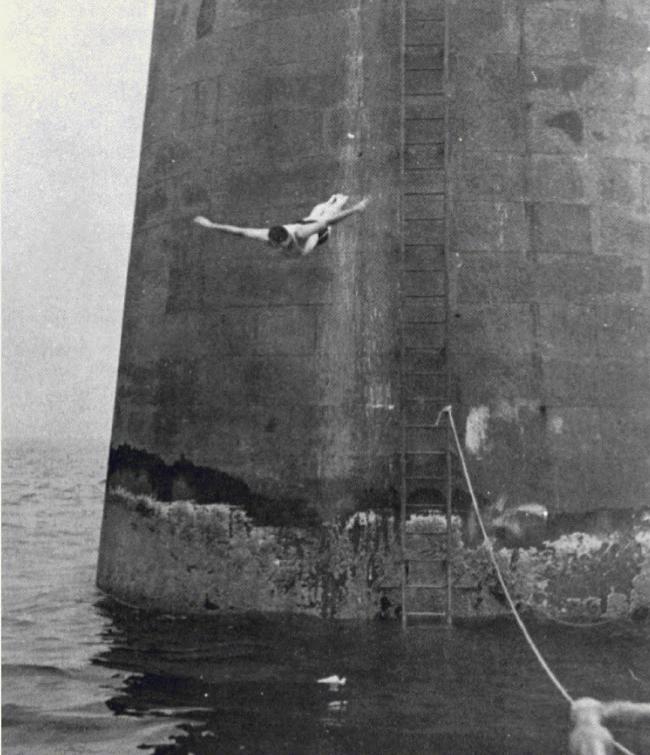

Captain Bennett started preparing for the worst. For evacuation, he built himself a basket suspended on a thick rope. According to contemporary witnesses, he actually used it from time to time, like that:

In April 1851, a lighthouse’s boat was lost to a gale, and the captain went to Boston to buy a new one. His two assistants stayed on the light.

A new storm began brewing. Captain Bennett hastened back to Cohassett, but it was too late for him to get to the lighthouse: the storm was already too strong. The captain stayed onshore and (I am sure) was gnashing his teeth. A captain feels on land as a fish out of water. It impossible to breath deeply, not enough oxygen.

The storm grew stronger each day. By April 16, five days after Captain Bennet’s return to Cohasset, it was already wrecking havoc on land. Boston had become an island. A few houses were washed away from Cohasset shore, as well as a school building from Long Island in Boston Harbor. Overnight on April 16 people onshore had seen the light flashing from the lighthouse, had heard desperate sounds of its fog bell.

Next morning, there were no traces of Minot’s Light.

It didn’t last even a year and a half.

Eventually, the bodies of the two Josephs, two keeper’s assistants, were washed ashore.

Granite Tower

Next version of Minot’s Light was built by the military — US Army Corps of Engineers. The design was personally led by the Chief Engineer Joseph Totten. One of the Corps of Engineers main missions was (and still is) building fortifications. Totten approached building the lighthouse based on that experience. He designed a tower with a 40-feet high soid granite base (the full lighthouse height is 114 feet) — precisely what his predecessor deemed impossible.

The lighthouse construction went from 1855 till 1860 and cost three hundred thousand dollars (old, real dollars). That made it one of the most expensive lighthouses in the US history (according to Wikipedia, the most expensive). This version of Minot’s Light is considered to be one of the most remarkable US engineering achievements in the 1800s. For sure, one of the most important achievements of General Totten’s career.

Until the construction was over, the part of the lighthouse was played by a lightship. These floating lighthouses are yet another remarkable part of New England’s historic landscape, and definitely deserve their story to be told separately.

The new lighthouse was lighted on November 15, 1860, and since then till now it stands there and gives light. And does it in a slightly unusual way. Typically, lighthouses are just flashing with a certain frequency (for example, Boston Light is flashing every 10 seconds). Minot’s is different: it flashes once, then a pause, then flashes four times, a pause, and three more flashes. The entire sequence is repeated every forty five seconds.

One-four-three is the number of letters in I love you. This somehow makes Minot’s the lovers’ light. It is considered very romantic to kiss each other in its view, especially on February 14.

Finally, an oil painting.

Scituate

First time I saw Minot’s Light up close was on a sail to Scituate, a coastal town further south from Cohasset. Minot’s Light was well visible from a beach in Scituate, especially with a long zoom.

And there is the light on our way to Boston. In the background, to the left: the control tower of Logan International Airport; to the right: the giant white eggs of the waste water treatment plant on Deer Island.

It’s been over hundred and fifty years now, and the lighthouse still stands perfectly still.

General Totten had done his job well.

Night

At night, in the dark, lighthouses are at most in there own element, so to say, but it is also when it is hard to take a photo.

Here is one Minot’s photo from our night sail to Provincetown, with the white dot of a plane on an approach to Logan Airport above the lighthouse.

Cohasset

Couple of years ago we were on a training overnight bike trip with my youngest daughter, and passed through the coastal town of Cohasset. There is a nice little harbor in Cohasset (too shallow for our boats, so I never sailed there), and there is a very interesting memorial to Minot’s Light there.

The lighthouse itself, though distant, is clearly visible from the coastal road leading into the town, — as well as the rocks between it and the coast, raison d’être for its existence. It’s also visible from the harbor, like a little insect looming on the horizon (be sure to click to enlarge the photo).

Somewhere here, onshore, there was a house for the lightkeeper and his assistants when they were away from lighthouse. We didn’t see (or didn’t recognize) the house itself, but between a small shack with the sign “Cohasset Harbormaster” and the local yacht club, there was a replica of Minot’s Light lantern with a part of its authentic Fresnel lens, which was replaced with modern optics in 1987–1989 (by a helicopter!).

It stands on a few granite slabs from the lighthouse, which were replaced back then during the renovation.

Next to it there is a real fog bell from Minot’s Light.

Also right there there is a newly open memorial to two assistant keepers, two Josephs, who perished when the hurricane destroyed the lighthouse.

They kept a good light — well said!

Snow

Minot’s Light was the favorite lighthouse of Edward Rowe Snow, the famous Boston marine historian and “Flying Santa”, of whom I wrote before. In his now classic book, “The Islands of Boston Harbor”, he included a chapter on Minot’s Ledge and its light, — the only place in the book outside of Boston Harbor. The photo of a giant wave breaking over Minot’s Light (which I put in the beginning of this post to catch your attention) is also from that book. Snow took it himself, in 1944.

Back when keepers still lived at Minot’s, Snow would often come visit them on a motorboat or a kayak. From time to time he would climb the ladder from the water surface to the keeper’s dwelling entrance — all sixty five feet — and dove down, to the horror and excitement of his little daughter and to the displeasure of his wife.

On this video, shot in 1962, he celebrates his 60th birthday.

After the lighthouse was automated, Snow kept diving from Minot’s Light while leading his lighthouse tours. Eventually Coast Guard’s Boston command had to ask him to stop.

Auctioned Off

Turns out, a few years ago the Coast Guard had auctioned off not only Graves Light (about which I knew before), but also Minot’s Light as well. In 2014, it was bought for 222 thousand dollars by a well-known Boston philanthropist Bobby Sager. What are his plans for the lighthouse, if any? It is unknown, he wouldn’t tell.

It is true that selling lighthouses off is inevitable. Who needs them in our age of satellite navigation!

But the heart is uneasy. Lighthouses are a very serious layer of the New England history. If (or, rather, when) they all get transferred to private ownership, who can guarantee their future?

And although, both for Graves and for Minot’s, the Coast Guard so far maintains their lights functional, a day can come rather soon when the lighthouse funding will dry up, and they will go dark forever.

For those of us who live slow life and navigate the old-fashioned way, with a compass and a chart, life will become just a little bit more dangerous.

And just a little bit less beautiful.

Subscribe via RSS