Brant Point Light

In my Peddocks Island report I started recounting my slow-moving project to explore all the islands in Boston Harbor. There is also another, even slower-moving project: to explore the Boston area and Massachusetts lighthouses. Ideally, this exploration should happen by sailboat, but in real life, we reached some of them by bike or on foot.

It seems like my plan for this year is to review one lighthouse a month, and the lighthouse for the month of June happens to be Brant Point Light on Nantucket.

Before I begin, though, I feel that I have to say a few words—or perhaps to sing a love song—about the island of Nantucket itself. As Melville famously described it in Moby-Dick,

Nantucket! Take out your map and look at it. See what a real corner of the world it occupies; how it stands there, away off shore, more lonely than the Eddystone lighthouse. Look at it—a mere hillock, and elbow of sand; all beach, without a background.

A few years ago, while touring Cape Cod on a bike with my Father, I finally reached that island away off shore, and got captivated right away by its special, lonely and wind blown character. Not to mention its charming and stylish typical New England town with cobblestones.

Since then, every time my Father and I bike down the Cape we make a point to catch a ferry to the island of Nantucket.

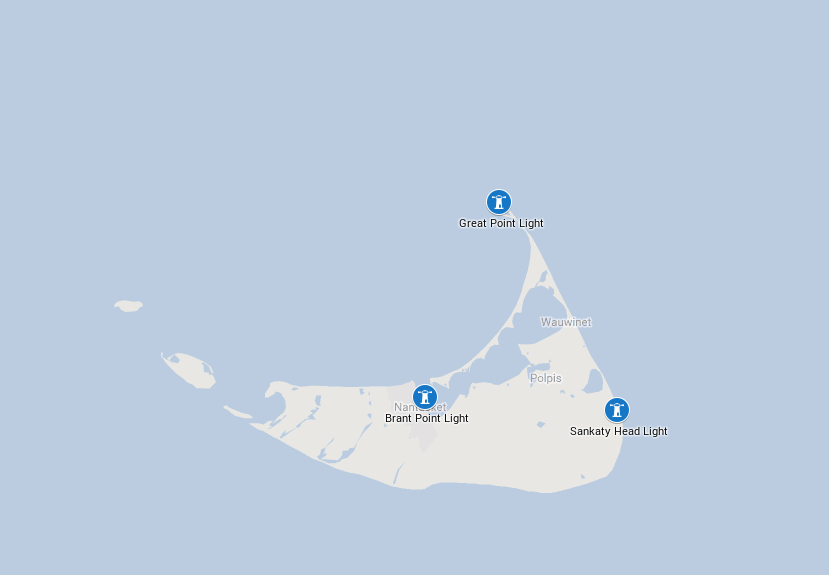

There are three lighthouses remaining on the island: Great Point Light, Sankaty Head Light and Brant Point Light. We have explored all three of them, and all three will be documented here in due course.

As you can see, while Great Point and Sankaty lights help boats to navigate around the island, Brant Point Light is different. It marks the entrance to the beautiful and only Nantucket Harbor.

We have not reached it on our own boat yet, but this is how we saw Brant Point and its Light on our first visit, entering the harbor in a ferry:

The lighthouse earned its place in the record books for a few reasons, some of them of dubious nature, but the first one is quite respectable: it is the second oldest lighthouse within the present United State. The disclaimer about “present” is obligatory: the light was built in 1746 and thus is older than its country.

The history books preserved the names of the three Nantucket residents who were directed to oversee the light construction: Ebenezer Calef, Obed Hussey and Jabez Bunker. As weird as their names may sound today, these three gentlemen were certainly white and Anglo-Saxon, just members of the island’s then big and thriving community of Quakers. Most Quakers had exotic Biblical names, and this fact plays an important part in Moby-Dick.

And since Moby-Dick was mentioned, it is impossible not to talk about whaling. In the eighteen and nineteen centuries whale oil (and especially sperm oil, the oil on the sperm whale) was what petroleum oil is today: a wander liquid that runs the economy. Whale oil was used for lighting, as machine oil, to treat metal, in medicine and in cooking. Just as today, oil revenues were enormous, distorting the overall economy. A few people got very rich.

Unlike the crude oil, though, whales live out in the ocean, and oceans don’t belong to any particular country. Any coastal place could have become the world’s top whaling center. Somehow the tiny Nantucket managed to be that place.

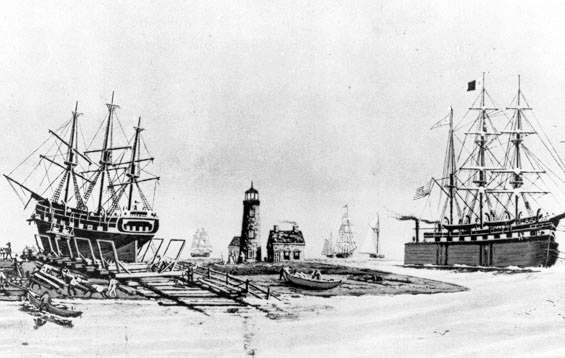

On this undated (“early”) engraving you can see Brant Point Light and two whaling ships being built nearby.

As you can see, the lighthouse on the engraving looks quite different from what we see today, and that’s a good reason to mention one more record: out of all US lighthouses, Brant Point Light is the one that was rebuilt the most times. The current version is its tenth incarnation.

The whaling business probably explains why the islanders were so persistent in maintaining the light. For many years consistent navigation was critical for their economical survival. By the way, the light was funded through taxes paid by the ships visiting the harbor.

The causes for so numerous lighthouse rebuildings were mostly commonplace: fires and hurricanes. One cause, though, was more specific for Cape Cod: the continuous movement of sand, both on land and underwater, leading to the continuous changes in shipping channels.

For example, here is the previous tower, built in 1856:

It is made out of brick, well built, and stands there today with no problems, except for one: it is now just too far from the channel to be used for navigation.

The current tower was built in 1901. It is 26 feet high, which makes it the lowest lighthouse in New England. Here comes another record!

Many lighthouses, in addition to being a navigational aid, elicit a strong emotional response. That response, however, is usually directly tied to navigation: joy, relief, or just a feeling of deep satisfaction that you ended up being where you were supposed to be.

Brant Point Light, in addition to that, is also directly tied to Nantucket, the island and the town. It stays at the corner, as it were, of the entrance to the harbor, and when you do enter, go around the point and the light, peer around the corner (just as the sunset ferry on the photo below), and see right away the houses, and the boats, and the docks, and the white spires of Nantucket, that wonderful island out in the ocean,—and the lighthouse welcomes you, opens you the doors to that beautiful corner of the world.

While any kind of arrival to Nantucket by sea guarantees great views of the lighthouse, it can also be explored by land, on foot or by bike. That’s exactly what we did during one of our visits: biked to the Coast Guard compound, left our bikes at the entrance to the beach, and walked on to appreciate the quintessential Cape Code landscape: sand, and sky, and sea, and a lighthouse.

We took that photo back then on film with a very cheap, plastic, 30 years old Soviet camera. That explains its high energy and spirituality.

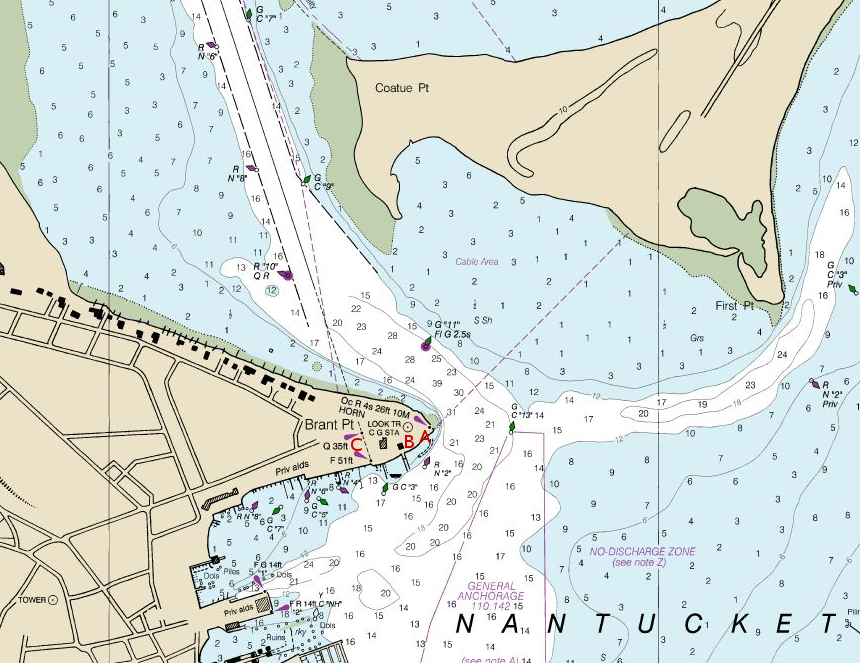

Now back to the buildings inside the Coast Guard compound. Here is the navigational chart of Brant Point and the vicinity:

(А): the current lighthouse at the very tip of Brant Point. (В): the previous tower (1856), we’ve seen its photo earlier (unfortunately nowadays it does not have a lantern anymore). The Coast Guard is based in that tower and in the old lighthouse keeper house. (С) an interesting couple of lights called range lights (built in 1908). When entering the channel by boat, coming from seaward, one has to visually put them in a vertical line, one above another. That would mean that one is following the channel along its centerline (this imaginary lined is drawn on the chart above, first as a dashed line and then solid).

Here is how they look from the channel, behind the shore cottages mansions. On the right—the old lighthouse tower, on the left—the range lights, now out of the vertical alignment, since we already started our turn around the point.

One more view at Brant Point, at a different time of day, and from a different point of view (no pun intended), so the buildings are located differently relative to each other. On the left: the old tower; in the middle: one of the range lights; to the right: the current Brant Point Light, at the very tip of the point, the way it is supposed to be.

As is noted on the map, Brant Point Light is occulting: it shines steady red light for 4 seconds, then a short flash of darkness, and again red for 4 seconds. Originally the light color was white, but with more and more cottages mansions being built, it eventually started blending in with the land lights, and had to be changed to red.

The range lights, however, are still white. The top light is lit continuously; the bottom is continuously flashing.

Leaving Nantucket on a ferry after sunset, in the dusk, I spent long time seating at the stern and looking back at the lights flashing. In addition to the Brant lights, the red and white buoy “NB”, that marks the shipping channel, was flashing the letter A in Morse code (dot, dash); and then Great Point Light became visible as well (bright white flash every 5 seconds). Soon I could not see the land at all. Only buoys and lighthouses were shining out there as a hand-made constellation.

On a summer night, warm and clear, it is good to sit on open deck, not think any particular thoughts and just look at the Nantucket constellation.

And then we sailed too far away from the land, and they all disappeared, one after another. Only the darkness of night remained, and the real, heavenly stars.

Subscribe via RSS